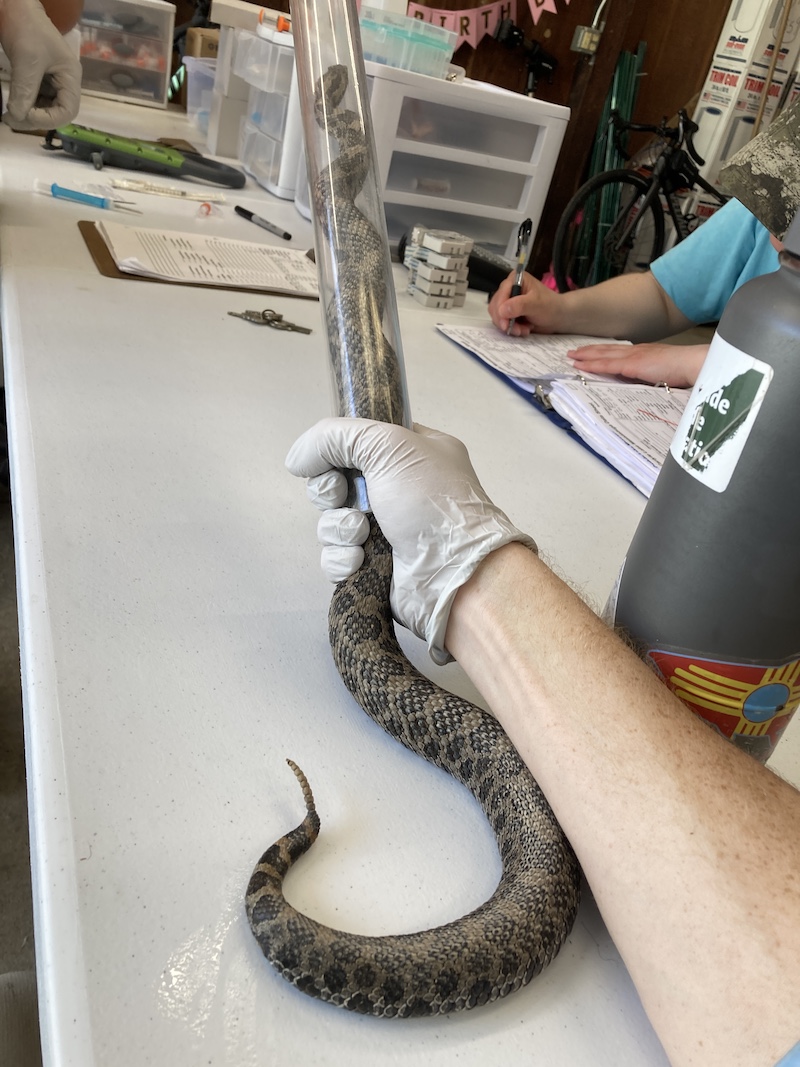

Researchers with the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Wildlife Epidemiology lab carefully place a massasauga rattlesnake in a bucket for further study. Photo by Mike Dreslik.

Snake Fungal Disease Imperils Illinois’ Smallest Rattlesnake

In 2010, Sarah Baker, then a graduate student at the University of Illinois and working with the Natural History Survey and now an assistant professor of biology at McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana, found something strange. It was a massasauga rattlesnake, an endangered species in Illinois, basking in short grass on a summer day, an unusual behavior. The snake’s head was deformed and swollen. She contacted Mike Dreslik, now the Illinois Natural History Survey Director, who called friend Matt Allender, a wildlife epidemiologist, to come have a look.

“I was thinking I was going just to find smushed head from hits by cars on the nearby road, and what we found was not at all that,” Allender recalled. “There were these large facial swellings and disfiguration of the entire head.”

When Allender, who is the Director of the Wildlife Epidemiology Lab at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, put specimens under a microscope, he found that the sores on the snake came from a fungus. It was Ophidiomyces ophidiicola, a deadly fungus that infects the bodies of snakes, causing what is often named Snake Fungal Disease, or SFD. For the first time, that disease had been found in snakes in the wild.

A Fungal Infection with Mysterious Origins

Wild snakes can become ill, though a typical person may not notice symptoms on a snake that quickly slithers across the path. Other animal groups have recently been documented with illnesses. Turtles are common hosts of ranaviruses, bouts of avian flu have recently decimated chicken populations, chronic wasting disease affects deer in Illinois and white-nose syndrome threatens bat populations in North America.

But fungal diseases are a different beast entirely, and beyond athlete’s foot and ringworm, are often unfamiliar to humans. Our internal body temperature is hot and inhospitable to the spores of fungi, even if contemporary media such as “The Last of Us” have many on edge about the possibility of a fungal outbreak.

Cold-blooded animals are much more susceptible to fungi, as their body temperatures can get down to the temperatures needed for spores to spread. Amphibian populations have been decimated in the past three decades by chytrid fungus, and in eastern massasauga rattlesnakes, a cooler body temperature, combined with their preferred wetland habitat, is the perfect combination for fungal infection.

Researchers with Allender’s epidemiology lab test rattlesnakes for Snake Fungal Disease using a cheek swab. They have found the disease present in about 25 percent of snakes sampled, a high figure. Of those infected snakes that researchers are able to accurately track, up to 90 percent of them succumb to the disease.

“Massasaugas are sensitive, certainly, to this pathogen, and we’re not quite sure why,” Allender acknowledged. “Their body type, scale type, habitat or infection load could all play a role in why massasaugas seem to have a higher mortality rate.”

Once infected, the snake’s body grows lesions. Its smooth, tightly locked armor begins to fail, seeping fluid. The snake’s eyes crust over, making hunting rodents more difficult. Once the infection has gotten to this stage, Allender’s lab found that the fungus has spread throughout the snakes’ entire body.

“Even though the disease is mainly in their skin, their body reacts, and they die from liver and kidney effects,” Allender stated.

It’s a cruel death, for an often-misunderstood species, and researchers have theories—but no answers—as to when the disease started showing up in eastern massasaugas. A spread from the pet trade cannot be ruled out, and it’s true that the disease is found in captive snakes. But detection tools are also improving, and scientists remain unsure if the disease has been silently killing eastern massasaugas for decades, or even centuries.

A Snake in Peril

Eastern massasauga rattlesnakes can be found by walking transects in suitable habitat, either in a straight line or an irregular line. Mike Dreslik has been surveying eastern massasaugas since 1999, running one of the longest continuous rattlesnake monitoring projects in the country. In that time, he has gotten better at spotting the snakes, but their camouflage and cryptic behavior still make his transects a challenge.

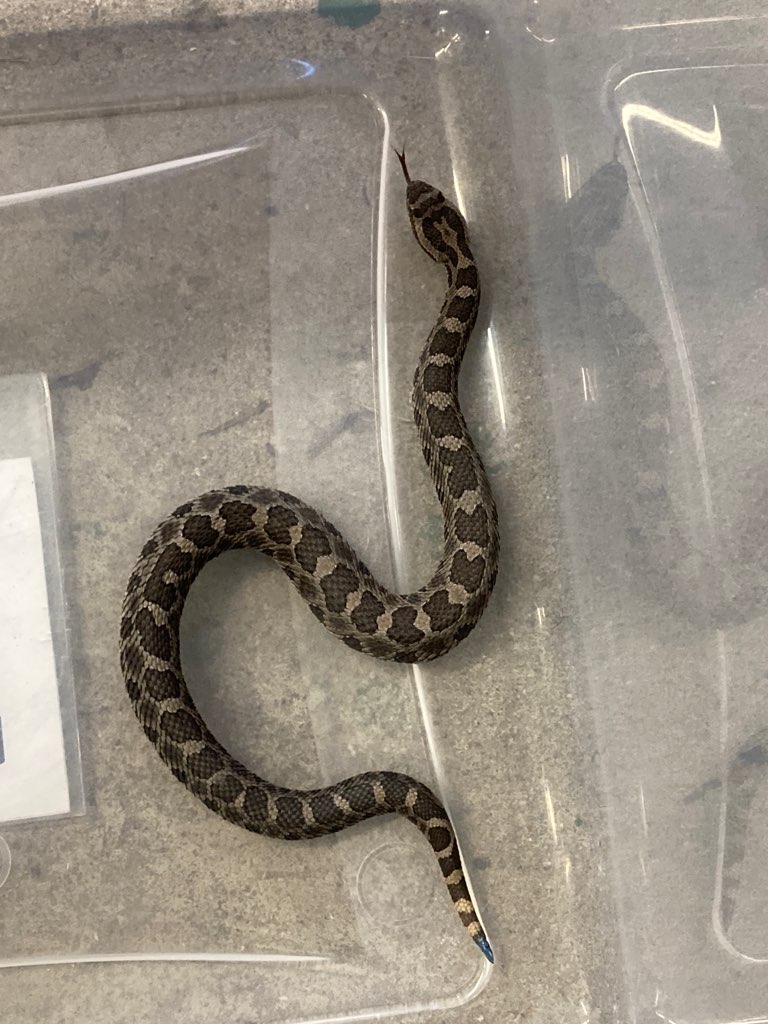

Once a snake is spotted, he and his team proceed to safely capture it. Dreslik grasps the snake with a long pair of flexible tongs, called a “Gentle Giant.” The rattling snake is placed into a pillowcase, then into a bucket. Snakes which have been captured before can be easily identified by bright paint on their rattle. New specimens are transported back to the lab, where they undergo a reptile physical exam.

With a snake secured in a plastic tube, Dreslik and team swab it for Snake Fungal Disease, take measurements, determine sex, weight, collect a genetic sample and take lots of photos. Massasaugas, like zebras, tiger salamanders and jaguars, are identified at the individual level by the differences in their body blotches.

Why go to all this trouble, wading through shoulder-high prairie looking for venomous snakes, prodding them into tubes, and taking measurements, for almost 30 years? As it turns out, Snake Fungal Disease is not the only threat that eastern massasaugas face. They are a state endangered species, and with that designation comes the need to know just how many of them exist in Illinois, and where they are reproducing.

Once found across the northern two-thirds of the state, numbers declined as a result of the drainage of prairie marshes and agricultural practices. They prefer wetland habitat, and need holes in the ground, usually dug by crayfish or rodents, in which to overwinter. Before European settlement, that habitat stretched along riverways in the northern two-thirds of the state and made up much of what is now Chicago and its suburbs.

Even through the 19th and 20th centuries, massasaugas hung on in the marginal habitat around barns, in pastures and in unplowed prairie potholes. But with the mechanization of agriculture, and the expansion of corn and soy fields from fencepost to fencepost, massasaugas faced habitats without rodents to eat or crayfish holes to hibernate in over winter.

“Over time, when you have smaller populations on these smaller, isolated patches, they eventually blink out of existence just of natural causes,” Dreslik said. “It’s what’s called the extinction vortex.”

Today, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are restoring eastern massasauga habitat, and there is hope for recovery of the species. Genetic testing has so far shown that eastern massasaugas are not yet suffering from the kinds of genetic bottlenecks that have happened to other imperiled species. A genetic bottleneck happens when population numbers reach a low enough number that inbreeding accentuates negative mutations. These mutations can compromise immune systems, lead to deformities, or otherwise reduce the health of the remaining animals.

Eastern massasaugas have not rebounded to sustainable numbers, and that is in no small part due to the constant threat posed by Snake Fungal Disease. But the snakes are still out there. They are still hunting rodents, bringing balance to the ecosystem. Their venom may yet hold secrets for human medicine.

Mike Dreslik knows what it will take to bring them back from the brink: “A focus on retaining quality habitat can be likely good enough. Some of that is removing and decommissioning roads, defragmenting habitat…it’s not evolution that’s driving the species toward extinction…it is human dominated causes.”

Hugh Gabriel is a writer, educator and occasional herpetologist who calls Minneapolis home. He works at the Bell Museum of Natural History, and can often be found travelling across Minnesota, sharing his love for Midwest ecosystems with the public. Gabriel has a special affinity for frogs, prairie flowers and a long day of fishing on a clear lake.

Submit a question for the author

Question: My question wasn’t answered. I belong to braidwood recreation club in braidwood Illinois next to the braidwood dunes. Is there any eastern massages snakes today in the area. Braidwood recreation is an old strip mine area with all areas filled with water. I have grandchildren that venture out in the club. I know 25 years ago they were sighted.

Question: Is there eastern massasaugas still around Braidwood dunes . I know 20 years ago there was sightings of the snake there. Are there any today?

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Explore Our Family of Websites

Similar Reads

It’s Clam Time on the Illinois River!

February 2, 2026 by Sarah Douglass, Jason A. DeBoer, Andrya L. Whitten Harris, Alison Stodola

Tiny Threatened Fish Species Re-introduced for the First Time

February 2, 2026 by Hugh Gabriel

She Finds Rare Prairie Clover – Missing Since 1873

November 3, 2025 by Stephen Packard

Living with Wildlife: Be Tick Aware

November 3, 2025 by Laura Kammin

Determining the Threat of Local Extirpations for Illinois’ Rare Plants

November 3, 2025 by Brian Charles, Paul Marcum, Greg Spyreas, Eric Ulaszek, David Zaya, Brenda Molano-Flores

Chronic Wasting Disease Surveillance in Illinois – Fall 2025 and Beyond

November 3, 2025 by Christopher N. Jacques

Nature’s Seasonal Events

November 3, 2025 by Carla Rich Montez

The Enigmatic Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus)

August 1, 2025 by Scott A. Eckert, Andrew Jesper

A Cohort of Sorts

August 1, 2025 by Patty Gillespie