Round-leaf sundew, Drosera rotundifolia. All photos by Brian Charles.

Round-leaf sundew, Drosera rotundifolia. All photos by Brian Charles.

Illinois has a fantastic diversity of ecosystems, ranging from cypress swamps in southern Illinois to bogs inhabited by carnivorous plants in northern Illinois. However, these ecosystems have largely been destroyed in the state, and many plant species have been lost along with them. Despite these losses, Illinois still contains more than 2,200 native plant species, which is the highest plant diversity out of any state in the Midwest.

Three-hundred and thirty plant species are designated as threatened or endangered in Illinois. Working with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, our group of botanists from the Illinois Natural History Survey set out to assess the threat of extirpation from Illinois for each of these plants. The main goals of this work were to help prioritize protection, allocate limited resources for land management and inform reintroduction efforts. To determine the likelihood of extirpation, we used a nationally standardized “Conservation Rank Calculator” tool to determine conservation status ranks in Illinois.

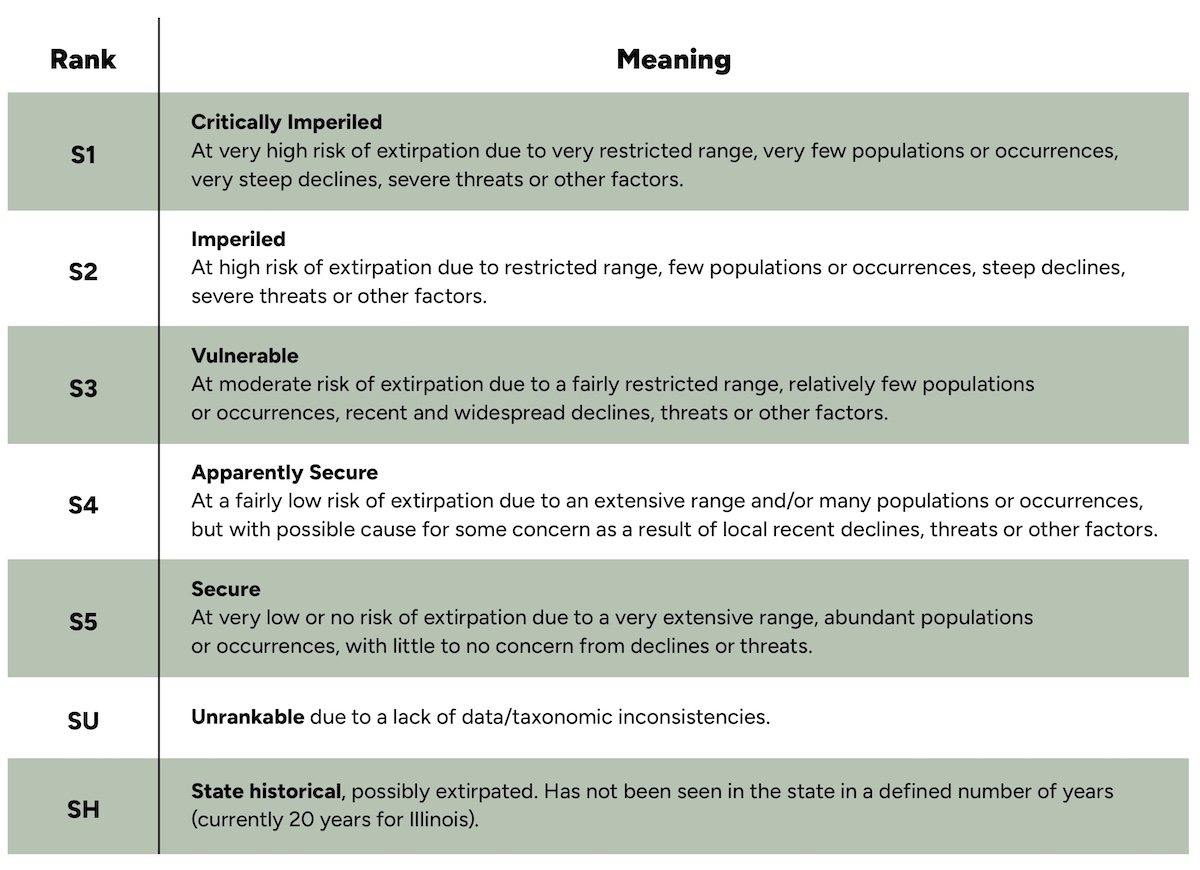

Subnational or state conservation status ranks (S-ranks) were developed by NatureServe, which is a non-profit scientific organization that works to synthesize data and inform conservation of rare species and ecosystems. S-ranks are part of a system of national ranks (N-ranks) and global ranks (G-ranks) that conservation biologists use to characterize how imperiled species or ecosystems are. Ranks primarily range from S1 (Critically Imperiled) to S5 (Secure), with other ranks that indicate situations such as a lack of data (see Table 1). The range, population size, threats, trends and other factors all help determine the S-rank. These ranks provide a way to consistently assess species in the United States and across the world with the same criteria, language and meaning. Ranking the conservation status of our state’s flora and fauna is important for keeping the natural heritage and integrity of our state alive. Without knowing the status of these species, we would be unable to prioritize which ones need conservation attention and would continue to lose more of them.

An essential part of accurate S-ranks is to ensure that there is recent information on the viability of each local population. However, many remote or hard to access sites are rarely visited, and there are more than 3,400 records of threatened and endangered plants in the state. Plant species populations are also constantly in flux and can be growing, declining or eliminated within short periods of time. Therefore, there were many populations that needed to be revisited before ranking to ensure that our ranks were as accurate as possible. We set out to visit many of these populations and made some extraordinary discoveries along the way.

During the process of ranking and assessing Illinois’ rare flora, we relocated 10 species that had not been seen in the state in more than 20 years!

We found bunchberry (Cornus canadensis), a forest ground cover herb that is a type of dogwood. This species was historically found in bogs and on sandstone outcrops throughout northern Illinois. Due to habitat destruction and degradation, less than five documented populations were potentially left in the state, and none of them had been seen since 2001. We relocated a population perched on a sandstone outcrop where it was last seen in Ogle County. Then, we found a new population in a bog in McHenry County. Bogs are one of our state’s rarest habitat types, making this discovery especially thrilling.

Another plant known to have become very rare is the cuckoo flower (Cardamine pratensis var. palustris), with only three documented populations in the state, which was last seen in Illinois in 2002. We found it in two northeastern Illinois wetlands.

Along the way, we also found new populations of rare plants such as bog buckbean (Menyanthes trifoliata) and butternut (Juglans cinerea).

One hundred and eighty of the threatened and endangered plant species which were ranked in Illinois were S1, indicating extreme vulnerability to loss from the state. These are species that could soon be gone from Illinois forever.

Most other species were ranked S2, indicating a high risk. An example of this is the bog buckbean (Menyanthes trifoliata), which is threatened by invasive species in wetlands, bog pollution and climate change.

A small subset of species were ranked S3, indicating vulnerability but not a high risk of loss. The information we generated for them may lead to their eventual removal from the threatened and endangered species list—a welcome reprieve.

We also discovered that there are many species which may be vulnerable but are growing under the radar because they are not on the threatened and endangered species list.

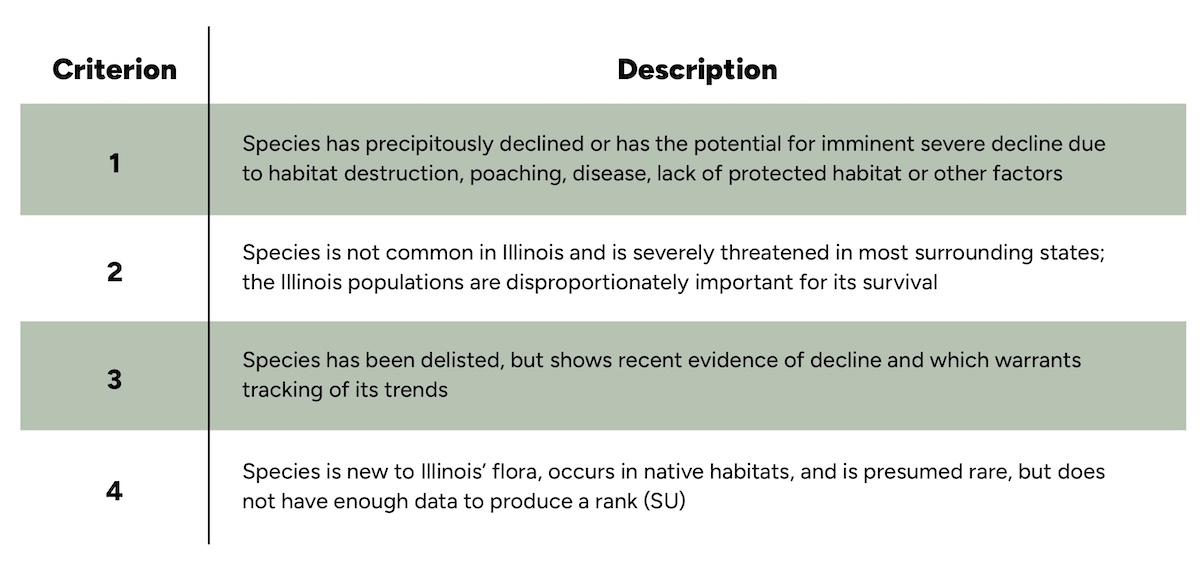

In addition to ranking the threatened and endangered species in Illinois, we created a new watch list for other plants that could be considered vulnerable. This list is designed to highlight plants that may soon become threatened or endangered. These are plants that we think we need to keep our eye on for various reasons. To be added to the watch list, a plant must meet one or more of the following criteria from Table 2 below:

One example of a watch list species is the nationally vulnerable clustered poppy-mallow (Callirhoe triangulata), for which Illinois has the largest number of populations in the country. Another plant on the list is the long-bract frog orchid (Dactylorhiza viridis), which is scattered across the state in just a few small populations.

An essential component of this work is helping to protect areas that contain plant species at risk of local extirpation. Unlike threatened and endangered animals in Illinois, plants are at the mercy of the landowner and therefore are not protected unless the land they occur on is protected. As a part of this project, we identified areas that have high concentrations of imperiled or watch list plants without habitat protection. With the new knowledge of the value of these habitats and their precarious status, hopefully landowners of some of these sites will protect them as Illinois Nature Preserves. Designation by the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission as a nature preserve is the highest level of protection a natural area can have in the state and ensures that all plants and animals found there are protected in perpetuity. There are more than 600 nature preserves in the state, and groups like the Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves help the state ensure these lands are properly managed and offer a way for the public to get involved in stewarding Illinois’ natural heritage.

This work marks an important step forward in prioritizing endangered, threatened and vulnerable plants and the lands where they are found. Although we have lost many plant species in the past, our job is now to keep a watchful eye on what remains. With diligence we can put Illinois at the national forefront of plant conservation.

To reach Brian Charles, email brianmc4@illinois.edu.

For more information, an open access journal article, “Illinois’ threatened and endangered plant S-rank update and a new Illinois plant watch list” is available online. DOI: 10.3375/2162-4399-45.3.5.

Brian Charles is a scientific specialist in botany at the Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He primarily works on Illinois threatened and endangered plant conservation.

Paul Marcum is a botanist at the Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois. He coordinates a team of approximately 20 scientists who conduct environmental surveys for the Illinois Department of Transportation. His research focuses on rare plant conservation, floristics, natural community studies and wetlands.

Greg Spyreas is an associate research scientist at the Illinois Natural History Survey. His focus is bringing about better conservation, restoration, management, monitoring, and understanding of natural areas and their floras/faunas.

Eric Ulaszek is a retired botanist and affiliate of the Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His works has focused on conducting surveys of threatened and endangered plants and plant communities.

David Zaya is an associate research scientist in botany at the Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. His research interests include rare species biology, plant-pollinator ecology and large-scale vegetation monitoring.

Brenda Molano-Flores is a plant ecologist at the Illinois Natural History Survey, Prairie Research Institute, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her research addresses several topics in plant reproductive ecology and conservation biology.

Submit a question for the author