The clam crew for 2025 Illinois River mussel surveys. Photo courtesy of Sarah Douglass.

The clam crew for 2025 Illinois River mussel surveys. Photo courtesy of Sarah Douglass.

Beneath the river’s surface, freshwater mussels are rebounding in the Illinois River. These humble benthic invertebrates filter water, stabilize sediments and quietly keep ecosystems humming. Importantly, after significant declines in the Illinois River due to historical clamming practices and poor water quality prior to the Clean Water Act, they are finally showing signs of recovery.

For the third year running, researchers from the Illinois Natural History Survey waded into the Illinois River to survey historic mussel beds. Malacologists at INHS alongside fish ecologists and a crew of field technicians from the Illinois River Biological Station spend a day each summer counting, measuring and identifying thousands of mussels. Their mission: track how mussel communities are changing and compare today’s populations with historic records.

Healthy mussel populations are more than a curiosity—they’re a sign of a resilient river. An individual mussel can filter gallons of water each day, and can be considered ‘sentinels’ of water quality. They provide food for fish and wildlife. Their life cycle is intricately tied to fish, as mussel larvae need a fish host to complete metamorphosis. Some mussel species can use a suite of fish as hosts, while others can use only one fish species. So, mussels depend on healthy fish populations, and diverse and abundant mussel communities indicate a similar fish population. Healthy mussel populations are a sign of a healthy river.

The Illinois River was home to a booming clamming industry in the late 1800s that produced buttons from mussel shells before the invention of plastic. After mussel populations crashed from over-harvest, shell collecting shifted from the button industry to supplying shells used as nuclei for an increasing pearl industry in the mid-1900s. Check out the Illinois State Museum digital exhibit for more information on the clamming industry. Unfortunately, mussel recovery was further hindered by human-induced change, like damming rivers and severe water pollution problems.

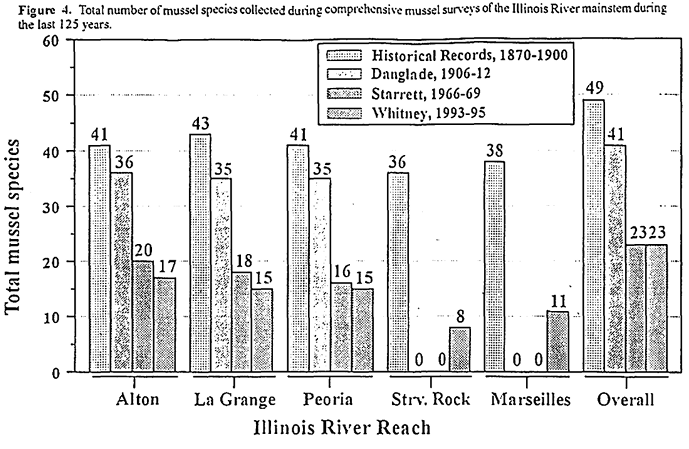

Historic mussel surveys in the Illinois River documented a depauperate mussel fauna, particularly in the upper reaches of the river (Richardson 1928; Starrett 1971). The most recent comprehensive survey of the Illinois River mussel fauna was conducted from 1993 to 1995 and revealed marginal repopulation of about half the historically present species (Sietman et al. 2001). The La Grange reach, which has been the focus of INHS’s survey efforts over the past three years, declined from more than 40 species prior to 1900 to only 15 species documented during surveys in the 1990s. Catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE), a measure of how many mussels were found for a given amount of search-time, was around 37 mussels/hour.

Since restarting surveys in 2023, thousands of native mussels representing 14 to 17 species each year have been collected. Species like threeridge (Amblema plicata), threehorn wartyback (Obliquaria reflexa) and mapleleaf (Quadrula quadrula) dominate the counts. Furthermore, multiple size classes of several species have been found, indicating a healthy, recruiting population. At most sampling locations, catch-per-unit-effort was much higher than in previous surveys, crews found more than 80 mussels per hour of searching at a particularly robust site.

In the summer of 2025, an Illinois-endangered species, the ebonyshell (Reginaia ebenus), was recorded for the first time in decades. This discovery is more than just exciting; it’s another hopeful sign that the Illinois River is bouncing back for more sensitive mussel species. Other species that were absent in the 1990s, such as hickorynut and lilliput, have been collected alive as well. Decades of pollution, habitat loss and invasive species once devastated mussel populations. Now, cleaner water, consistent management, and ongoing restoration efforts are helping native mussels reclaim their place in the river.

Like mussels, fish in the Illinois River have suffered from human impacts, including dams and levees that block their movement, water pollution and overfishing of many species (Mills et al. 1966, Schneider 1996). Fortunately, fish populations have proven to be resilient. Cleaner water, better management of invasive species, and targeted habitat restoration have led to increases in abundance and biodiversity (Whitten and Gibson-Reinemer 2018, DeBoer et al. 2019). Though challenges old and new continue to affect fish and mussels in the Illinois River, the dedicated efforts of managers and researchers across the watershed provide a positive outlook.

Although only a couple of sites can be surveyed in a day, each summer adds another piece to the puzzle of how this river’s benthic fauna is rebuilding. Comparison of today’s mussel beds with historic records help measure progress and guide future conservation.

So next time you’re paddling, fishing, boating or hiking along the Illinois River, remember beneath the surface a quiet comeback is underway. The mussels are telling us the river’s story—and it’s one of resilience.

DeBoer, J.A., Thoms, M.C., Casper, A.F. and Delong, M.D., 2019. The response of fish diversity in a highly modified large river system to multiple anthropogenic stressors. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 124(2), pp.384-404.

Mills, H.B., Bellrose, F.C. and Starrett, W.C., 1966. Man’s effect on the fish and wildlife of the Illinois River. Biological Notes; no. 057.

Richardson, R.E., 1928. The bottom fauna of the middle Illinois River, 1913-1925: its distribution, abundance, valuation, and index value in the study of stream pollution. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin; v. 017, no. 12.

Schneider, D.W., 1996. Enclosing the floodplain: Resource conflict on the Illinois River, 1880–1920. Environmental History, 1(2), pp.70-96.

Sietman, B.E., Whitney, S.D., Kelner, D.E., Blodgett, K.D. and Dunn, H.L., 2001. Post-extirpation recovery of the freshwater mussel (Bivalvia: Unionidae) fauna in the upper Illinois River. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, 16(2), pp.273-281.

Starrett, W.C., 1971. A survey of the mussels (Unionacea) of the Illinois River: a polluted stream. Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin; v. 030, no. 05.

Whitten, A.L., and D. K. Gibson-Reinemer. 2018. Tracking the trajectory of change in large river fish communities over 50 Y. The American Midland Naturalist, 180(1), pp.98-107.

Whitney, S.D., K.D. Blodgett, and R.E. Sparks. 1997. A comprehensive mussel survey of the Illinois River, 1993-95. Illinois Natural History Survey Aquatic Ecology Technical Report 91/11. 32 p + Appendices.

Sarah Douglass is a malacologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey where she works to conserve freshwater mussels and assess rare species through field surveys and environmental DNA techniques. Her research focuses on river ecosystems, species distributions, long-term population dynamics, and engaging with community science to better understand and sustain mussel populations across the state.

Jason DeBoer is a large river fisheries ecologist with the Illinois River Biological Station in Havana where he monitors fish populations on the Mississippi River. He has been involved with fisheries research and monitoring since 2006.

Andrya Whitten Harris is a Large River Fisheries Ecologist for the Illinois Natural History Survey at the Illinois River Biological Station in Havana. Her research focuses broadly on freshwater fish ecology, with the main area of research on the Illinois Waterway. She is currently working on leveraging long-term data sets to describe the distribution, relative abundance, and detection frequency of non-native and native fishes in Illinois.

Alison Stodola is a malacologist with the Illinois Natural History Survey in Champaign and serves as the acting curator of Malacology for the INHS Mollusk Collection.

Submit a question for the author