Smallmouth bass swimming right in murky waters. Photo by Michelson Fish Photography.

Smallmouth bass swimming right in murky waters. Photo by Michelson Fish Photography.

Fishing is not only a favorite pastime of people throughout the United States, it is also one of the largest sources of economic activity in the country. In 2020, revenue from recreational angling — $47.7 billion — was greater than that of Google — $37.9 billion, according to the American Sportfishing Association.

In Illinois, anglers fishing in streams, rivers and lakes throughout the state, excluding Lake Michigan, contribute an average of more than $900 million every year to local economies through direct retail purchases related to angling (gear, lodging, food, etc.). The American Sportfishing Association also noted that the same inland angling industry supports nearly 9,000 jobs with a total of more than $400 million in salaries and wages for employees throughout the state.

To put some of those numbers into perspective, the retail value of angling in Illinois is nearly twice that of Montana ($480 million), on par with Alaska ($939 million) and just less than the saltwater fishing industry in California ($995 million). While shy of the Land of 10,000 Lakes, Minnesota, which generates more than $2.6 billion in direct retail annually, the recreational angling industry in Illinois is still among the most valuable economic resources in the Midwest.

Given the importance of fisheries in Illinois, it is no surprise that conservation and restoration of aquatic life resources are focal points for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR). Within IDNR, the Division of Fisheries aims to enhance aquatic ecosystems and the communities of fishes they support through management and research efforts. Notably, IDNR strives to make informed management decisions using a variety of spatial and temporal fisheries population and community data.

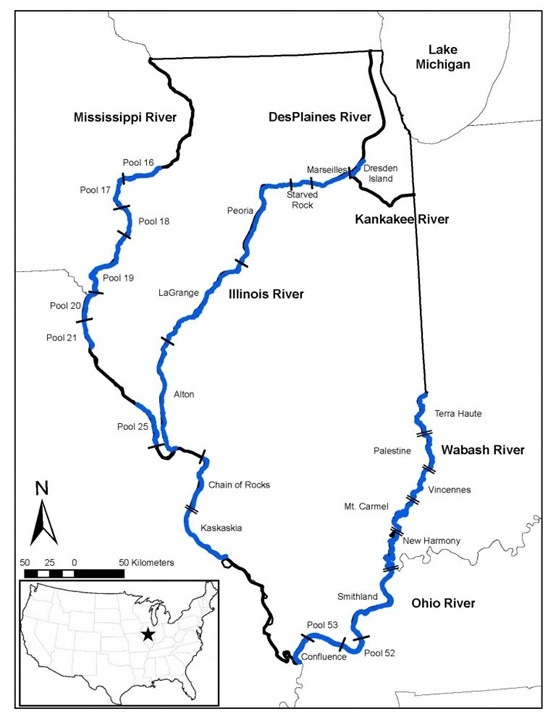

One particularly important source of fisheries data for fisheries management is the Illinois Natural History Survey’s Long-Term ElectroFishing (LTEF) program. Since 2010, the LTEF program has collected data on the entire Illinois River and on reaches of the Mississippi, Wabash and Ohio rivers during three six-week periods between June 15 and October 31 each year (Whitten et al. 2022). The program is based at the Illinois River Biological Station in Havana, one of the many Prairie Research Institute field stations around the state.

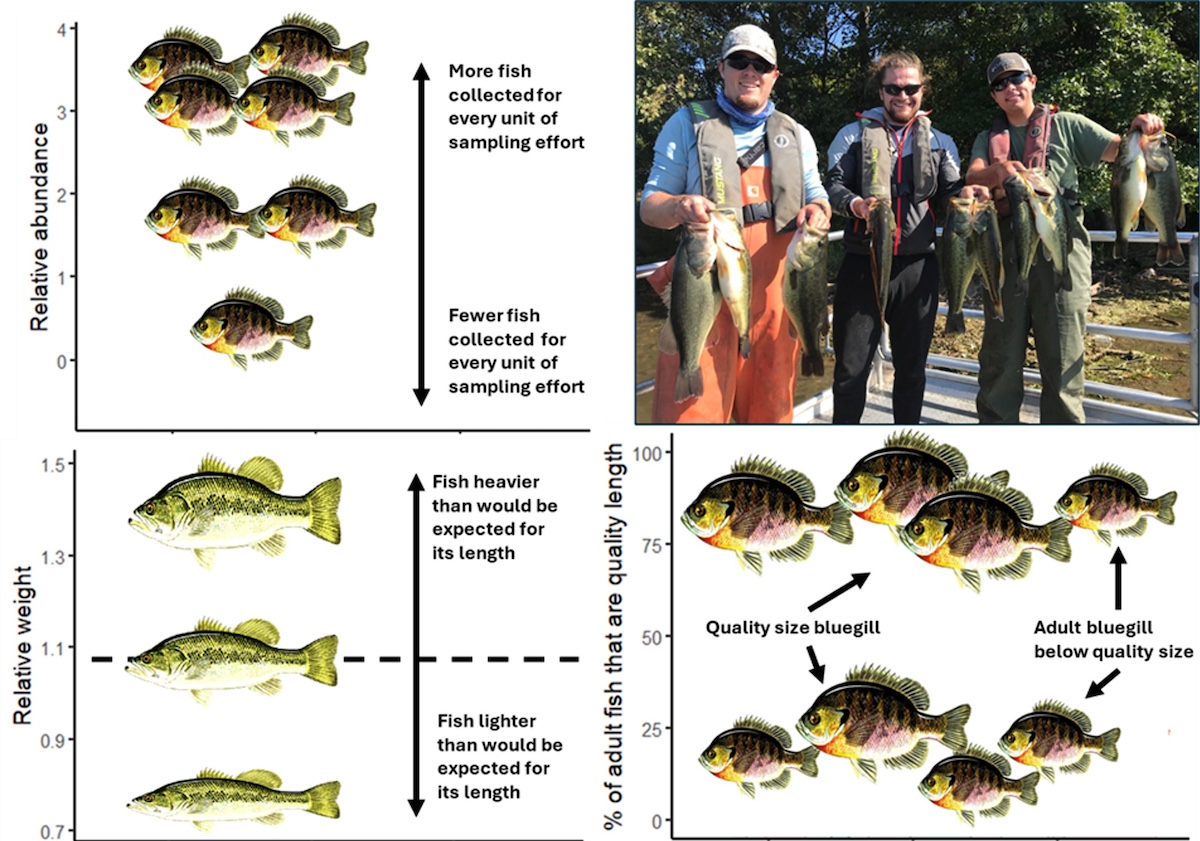

The LTEF program uses main-channel border randomized sampling to collect data that can be used to provide unbiased estimates of important fisheries metrics at the navigation reach or pool scale that can be compared over time. While there are numerous important fisheries metrics, including mortality and recruitment, in this article we focus on:

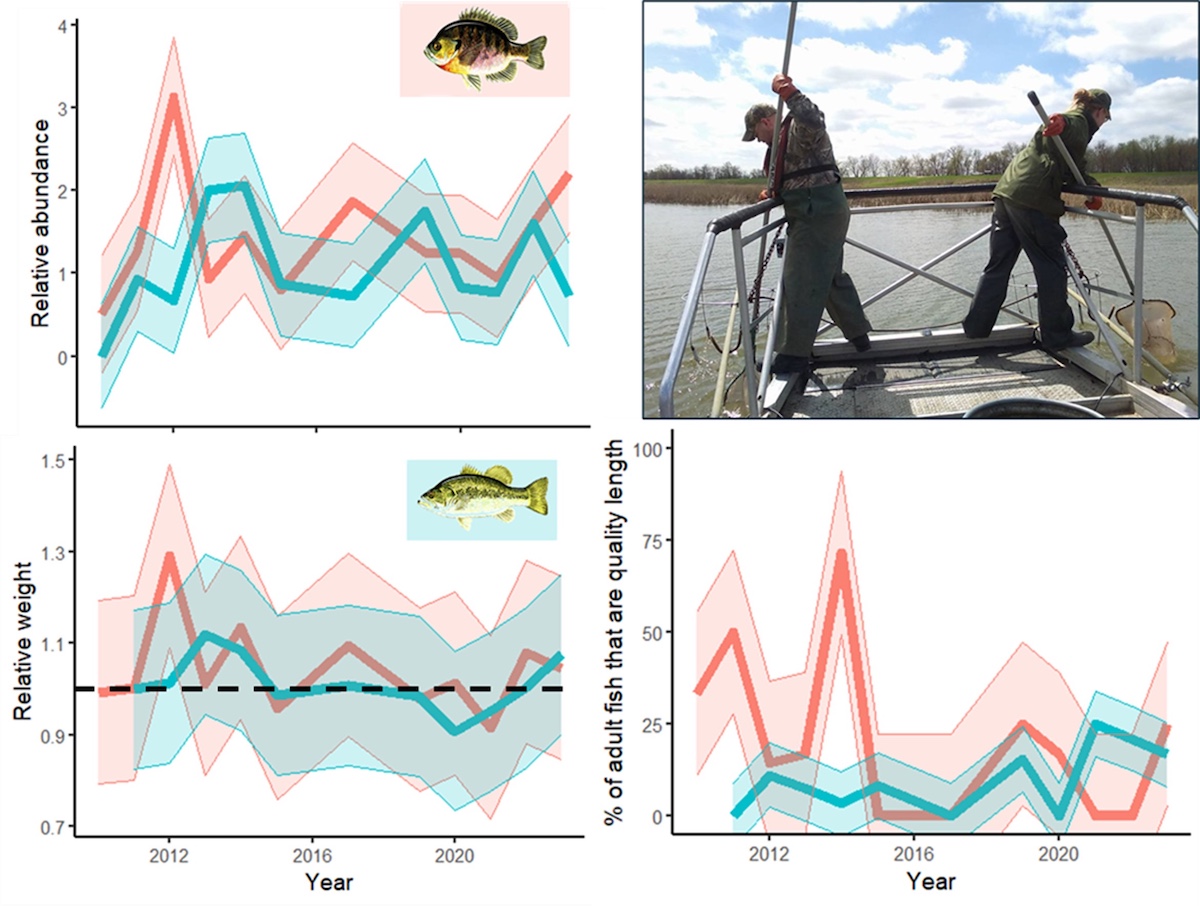

Because of the sampling design and long-term nature of the program, the data can provide insights into the ever-changing, dynamic fisheries throughout Illinois’ rivers (figure 2). For example, following a slight decline in relative abundance from 2017 to 2021, the bluegill population in Pool 16 of the Mississippi River bounced back in 2023 to its highest since 2012 (figure 3). Additionally, we notice that populations of both largemouth bass and bluegill have hovered around relative weights of 1.0 for the last 14 years, with a few peaks here and there, suggesting that, on average, the fishes have maintained a relatively healthy weight since 2010. We also see that the proportion of quality-length bluegills (greater than 5.9 inches) varies among years, by up to 50 percent in consecutive years, while the proportion of quality-length largemouth bass (greater than 11.8 inches) is a bit more stable but generally lower (figure 3). While these are just a few observations made from LTEF data, they represent an incredibly valuable tool for managers.

To understand and track the past and current state of Illinois’ riverine fisheries, long-term, unbiased data is needed for numerous species across rivers throughout and bordering Illinois (McClelland et al. 2012). Without long-term data, it is nearly impossible to make informed management decisions, identify appropriate interventions, or determine whether an intervention was successful. LTEF and other long-term monitoring efforts have directly helped develop and assess successful habitat restoration projects on the Upper Mississippi River (USACE 2022), inform invasive carp harvest programs on the Illinois River (Harris et al. 2025), and prove that the Clean Water Act revitalized the Illinois River fishery (Pegg and McClelland 2004).

Monitoring data is necessary to identify when and where management is needed, and if management efforts were successful. We also must be confident in that data.

Long-term data not only allows us to track changes over time to help guide regulation and management efforts but affords us a unique opportunity to learn.

Historical data can be used to guide future sampling efforts and improve the program’s ability to detect changes in important fisheries metrics. With decades of electrofishing data on Illinois rivers, we can refine our sample sizes to monitor more efficiently, carefully allocating resources and optimizing the value of our monitoring for the fishes and anglers of Illinois.

Sample size, or how much, how often, and where monitoring occurs, is a key decision for monitoring programs. Sample too little and we risk the “noise” of natural variability drowning out our ability to detect important trends in fish populations. Sample too much and, though we may gain useful precision in one place, we risk spending limited resources (nets, time, researchers, etc.) inefficiently, leaving blind spots on other critical species or river reaches.

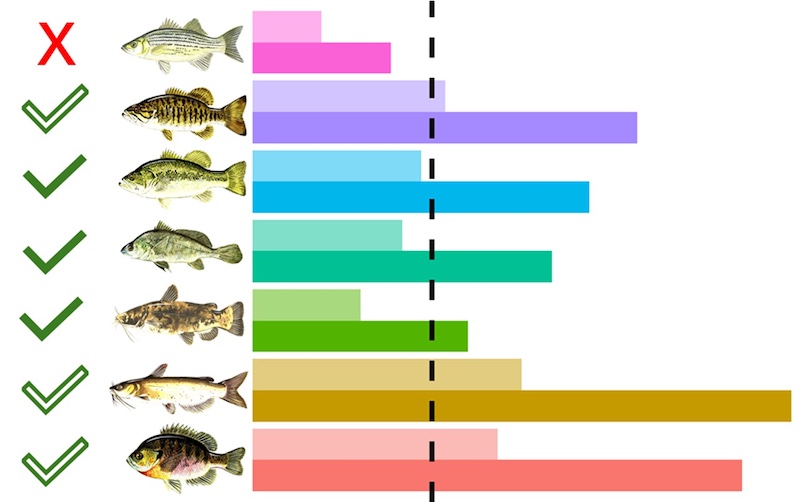

Recently, historic sample sizes were evaluated to determine if they are sufficient to detect “meaningful” annual changes in relative abundance, relative weight, and the proportion of quality-length adults for numerous important sportfish species. Managers set parameters for what defines a “meaningful” change, such as percent increase or decrease in a monitoring metric and the statistical confidence we have that our data would detect such a change, should it occur.

For example, based on historical variability of relative abundance in Pool 16 of the Mississippi River, we can identify a meaningful change in annual relative abundance for smallmouth bass, bluegill and channel catfish (Figure 4). However, our analyses also revealed that, by doubling the number of sampling days per year in Pool 16, we can extend that list of species to also include largemouth bass, flathead catfish and freshwater drum. Those additional sampling days also make it possible to monitor meaningful changes in relative weight for bluegill, largemouth bass, white bass, channel catfish and flathead catfish populations. Although doubling the number of sampling days in a Pool is no small task, the return for the effort is incredibly valuable.

With the support of IDNR, the program can make these and similar adjustments in Pools 17 and 20 to improve sportfish population monitoring in the Mississippi River. Unprecedented in river management, Illinois’ data-driven approach is a high-precision barometer to assess and rapidly respond to changes in sportfish populations to increase the value to anglers.

Fisheries management starts with data collection. You have to know what is going on beneath the water’s surface to make informed management decisions.

The Long-term ElectroFishing program, along with IDNR, continues to improve the quality and power of the data collected to assess how populations and communities of fishes are changing across our major rivers each year. This system-wide, data-driven approach using river fish monitoring to inform sampling effort and advise management sets Illinois apart from other states as managers and scientists continue to enhance the fishing experiences for Illinois anglers.

American Sportfish Association. 2020. Sportfishing in America: A Reliable Economic Force. Produced for the American Sportfishing Association by Southwick Associates.

Harris, B., M. Spear, J. Lamer, A. Whitten Harris. 2025. Monitoring to manage: The multi-agency approach to invasive carp in Illinois. OutdoorIllinois Journal.

Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2024. Division of Fisheries: 2024-2029 strategic plan for the conservation of Illinois fisheries and aquatic resources.

McClelland, M. A., G. G. Sass, T. R. Cook, K. S. Irons, N. N. Michaels, T. M. O’Hara & C. S. Smith 2012. The long-term Illinois River fish population monitoring program, Fisheries 37: 340–350.

Pegg, M. A. and M. A. McClelland. 2004. Spatial and temporal patterns in fish communities along the Illinois River. Ecology of Freshwater Fish 13: 125–135. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). 2022. Upper Mississippi River Restoration 2022 Report to Congress.

Whitten, A.L., J.A. DeBoer, J.T. Lamer. 2022. 60+ years of monitoring large river fishes in Illinois. OutdoorIllinois Journal.

Rob Mooney is an assistant quantitative ecologist at the Illinois River Biological Station at the Illinois Natural History Survey. He uses long-term data to help guide sportfish monitoring and management efforts throughout Illinois’ rivers. As an avid angler, he hopes to provide and interpret data that will help conserve fisheries throughout the Midwest.

Michael Spear is a quantitative ecologist at the Illinois River Biological Station. His work leverages statistics and computer programming to help fellow scientists and natural resource managers make data-driven decisions. A resident of La Grange Park, Spear proudly works to protect Illinois’ rivers on behalf of the communities through which they flow.

Brian S. Ickes (retired) was the principal investigator for the Long-Term Resources Monitoring Fisheries component of the Upper Mississippi River Restoration Program, a U.S. Congressionally funded partnership program among several federal natural resource management and research agencies and the natural resource management agencies of MN, WI, IA, IL and MO.

Andrya Whitten Harris is a Large River Fisheries Ecologist for the Illinois Natural History Survey at the Illinois River Biological Station in Havana. Her research focuses broadly on freshwater fish ecology, with the main area of research on the Illinois Waterway. She is currently working on leveraging long-term data sets to describe the distribution, relative abundance, and detection frequency of non-native and native fishes in Illinois.

Jason DeBoer is a large river fisheries ecologist with the Illinois River Biological Station in Havana where he monitors fish populations on the Mississippi River. He has been involved with fisheries research and monitoring since 2006.

David Glover is the Rivers and Streams Program Manager for the Division of Fisheries, Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Jim Lamer is an associate large river ecologist and Director of the Illinois River Biological Station at the Illinois Natural History Survey, specializing in aquatic resource monitoring and management. His research focuses on understanding the dynamics of native and invasive species within large river systems to inform sustainable management practices and understand long term drivers of system change.

Submit a question for the author