Photo by Courtney Celley, USFWS.

Photo by Courtney Celley, USFWS.

As the eastern tall grass prairie was converted to cropland in the 19th century, resident wildlife were profoundly affected. Initially some species benefited as small fields of corn, oats and wheat increased supplies of waste grain, weed seeds and insects available as foods. Greater prairie-chickens reached peak abundance in Illinois during this transition period. By the 1900s, cropland had almost completely replaced prairie and prairie-chickens were extirpated over most of the occupied range in the state.

As prairie-chickens declined, individuals with an interest in upland bird hunting began releases of ring-necked pheasants, a ground-nesting, gallinaceous bird native of central Asia. More than a dozen pheasant species occupy a variety of habitats from Japan to the Caucasus Mountains bordering eastern Europe. By the 1920s, ring-necked pheasants had been introduced throughout most of the United States; however, they most successfully established in areas formerly occupied by prairie, now considered the Cornbelt states including Illinois.

Ford County and Pheasants

Ford County in east-central Illinois lies in the Cornbelt and pheasants quickly populated the area following releases made by private individuals in the early 1920s. The state began releasing pheasants in 1928 (Robertson, 1958). Farmlands provided excellent habitat for pheasants during this period. Cropping systems included corn (52 percent), soybean (5 percent), oats (22 percent), alfalfa (4 percent), clover (4 percent), bluegrass pasture (6 percent) and other herbaceous cover (7 percent). Hay and pasture provided abundant nest cover and small grains supplied good brood foraging habitat. Waste corn and weed seeds provided winter food sources. Though nest destruction was significant in hayfields, the total acreage devoted to hay assured adequate reproduction to support high fall populations. The first five-day hunting season was held in 1915. The season was extended to 20 days after several years (Robertson, 1958).

In the years following World War II, Ford County developed a reputation as a prime pheasant hunting area in Illinois. County residents were joined by hunters from Chicago and the suburbs as well as hunters from southern Illinois and nonresidents from surrounding states. The opening day of pheasant season, November 11 (Armistice Day) at noon, caused a notable increase in the number of people in the small towns and villages around the county. Local businesses, restaurants, motels and gas stations noted significant boosts in sales especially early in the season. Local churches and service clubs hosted pancake breakfasts and chili suppers to accommodate hunters and as a fundraising activity. Members of service clubs owning farmland would lease their land to hunters for opening day.

Ford County continued to be a prime destination for pheasant hunters through the early 1970s. From 1956 to 1969, the average annual pheasant harvest in Ford County was estimated to be 41,700 roosters. Hunter effort averaged 106 trips per 1,000 acres (Preno and Labisky, 1971). With this history, it is not surprising that a strong tradition of pheasant hunting exists in Ford County.

Unfortunately for pheasants and pheasant hunters, massive changes in agricultural policy and practice brought about changes in crops and available habitat on farmland in the Cornbelt. Until the early 1970s, agricultural production was geared to the domestic market. As production increased and grain prices fell, farmers received incentives to plant fields to legumes and grasses to reduce grain production, incidentally, creating suitable nest cover for pheasants and other ground-nesting wildlife.

Beginning in 1974, farmers were encouraged to increase production for a burgeoning export market. In the Cornbelt, the massive shift to corn and soybeans virtually eliminated crops such as oats, wheat, legumes and pasture. In a few years, corn and soybeans made up 93 percent of Ford County farmland compared to 62 percent in the 1960s. Hay and small grains currently occupy less than 2 percent of cropland. The shift to continuous row crops occurred throughout most of the Cornbelt and drastically reduced pheasant abundance. In addition, a series of unusually severe winters in the late 1970s and early 1980s further reduced pheasant numbers.

Fortunately for pheasants and pheasant hunters, increased grain production and disruptions in export markets in the early 1980s reduced grain prices. Farm leaders called on the federal government to develop a strategy to assist farmers struggling with the depressed agricultural economy. In the effort to increase grain production, large acreages of fragile cropland had been converted from pasture to row crops increasing soil erosion and impairing water quality. Some of this land could be retired from production to reduce crop production. This effort to reduce crop production and control soil erosion through the planting of conservation cover of grasses and forbs, became known as the Conservation Reserve Program.

In St. Paul, Minnesota in 1982 a group of sportsmen and biologists, under the leadership of Jeffrey Finden, formed the Pheasants Forever organization. The new organization followed the Ducks Unlimited model and focused on pheasant habitat restoration. Local chapters were formed. Chapters held fundraising events and used the proceeds to restore grassland habitat on lands where grassland could remain undisturbed during the primary nesting season, from April 1 to August 1 in Illinois. Farmland enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program became a focus of many Pheasant Forever chapters.

Pheasants Forever chapters focus on grassland habitat restoration and education of the public regarding habitat requirements of grassland wildlife emphasizing that grassland habitats are among the most threatened in the United States. Naturally, pheasant enthusiasts in Ford County were eager to become involved. In 1985, the Illinois Pioneer Chapter of Pheasants Forever was formed, the first chapter in Illinois. The chapter held their first banquet in March 1985.

Between 1985 and 2025, chapter members, some new folks and some old timers, initiate numerous activities to promote conservation of pheasants and other species.

Each year, the dedicated members of the organization have held banquets and other events to generate funds for habitat restoration and educate the citizens of Ford County on how they can enhance the land for the colorful resident in his adopted home. The annual banquet is the primary event. It consists of a social hour and meal followed by raffles and a live auction of firearms, artwork, and outdoor equipment donated by local businesses and individuals. Funds generated are used to buy seed and seeding equipment to plant high quality grass/forb nest cover on Conservation Reserve Program fields, field borders and non-cropped areas. Funds have also been utilized to build some small wetlands scattered throughout the county.

The chapter also holds numerous annual events for area youth to foster an appreciation of outdoor recreation. Chapter members conduct hunter safety training, youth hunting opportunities and fishing derbies.

On the state level, chapter members were active in supporting legislation to establish the Illinois Pheasant Stamp, a forerunner of the current Habitat Stamp. The $5 stamp required of all pheasant hunters generated additional funds for habitat restoration projects by chapters and limited land acquisition by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

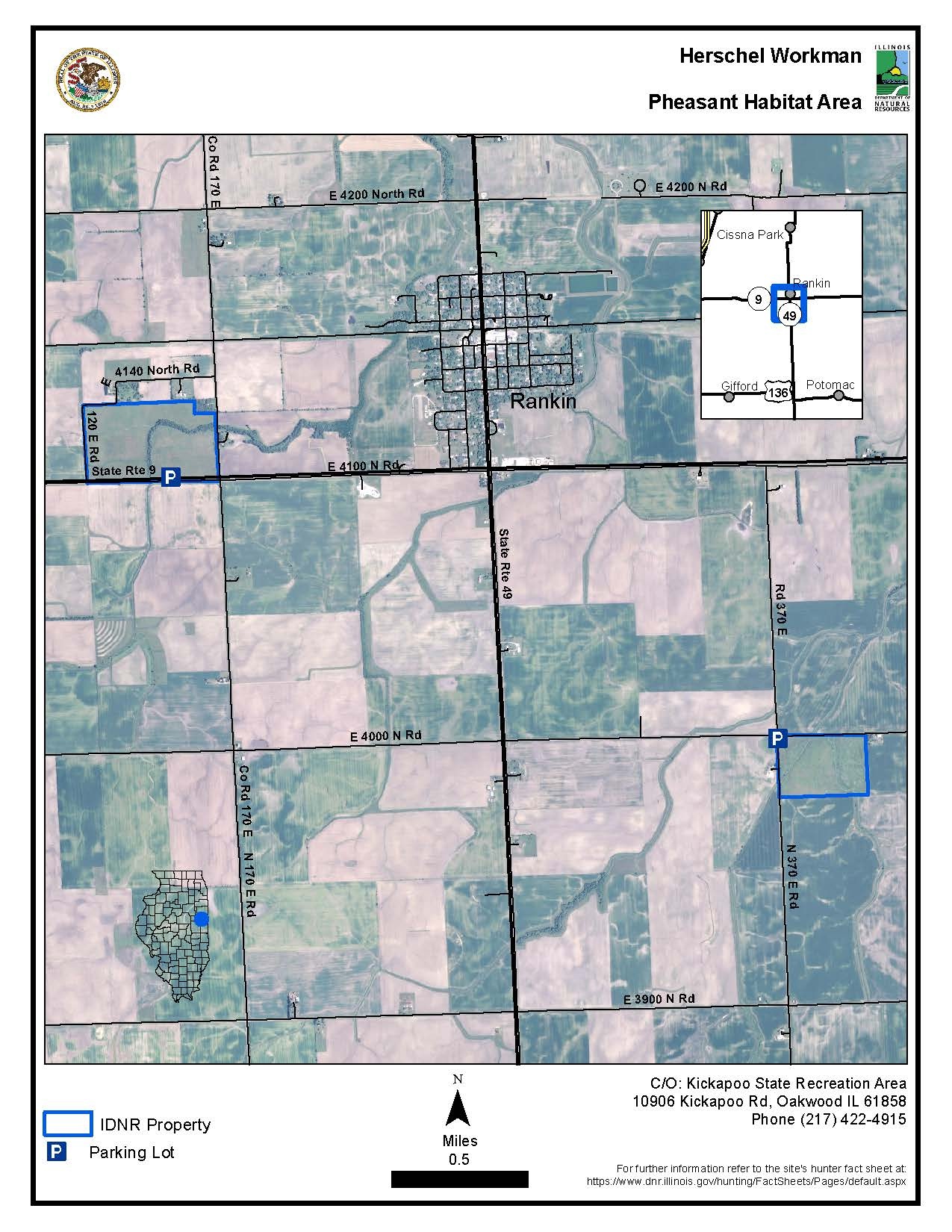

The Illinois Pioneer Chapter also developed a proposal for acquisition of the Herschel Workman Pheasant Habitat Area, a 120-acre grassland in Vermilion County for pheasant habitat and limited public hunting. It was the first pheasant habitat area acquired in Illinois.

On the national level, chapter members have met with United States Department of Agriculture and their congressional delegation to make recommendations for improving the wildlife benefits of farm bill conservation programs in successive farm bill legislation.

The work of the Illinois Pioneer Chapter of Pheasants Forever is noteworthy in their dedicated, consistent effort over 40 years. However, successful habitat restoration programs are dependent on the continued availability of USDA farm bill conservation programs. Very little land with appropriate habitat would be available without the soil rental and cost share funds provided by farm bill conservation programs. All of us with an interest in grassland habitat restoration must support adequate funding for farm bill conservation programs.

Literature Cited

Preno, W. and R. Labisky. 1971. Abundance and Harvest of Doves, Pheasants, Bobwhites, Squirrels and Cottontails in Illinois, 1956-69. Illinois Department of Conservation Technical Bulletin No. 4. 75 pp.

Robertson, W. 1958. Investigations of Ring-necked Pheasants in Illinois. Illinois Department of Conservation Technical Bulletin No. 1. 137 pp.

John Cole grew up in Bradley (Kankakee County). He graduated from SIU Carbondale with BA in 1968 then served two years in the U.S. Army as medical technologist at Tripler Army Medical Center in Honolulu. After graduating from SIU Carbondale with an MS in 1973 he began to work for the then Illinois Department of Conservation as District Wildlife Biologist, headquartered in Gibson City in east-central Illinois. In 1993, Cole became the Illinois Department of Natural Resources Ag and Grassland program manager in Springfield, working there until his retirement in 2008.

Submit a question for the author