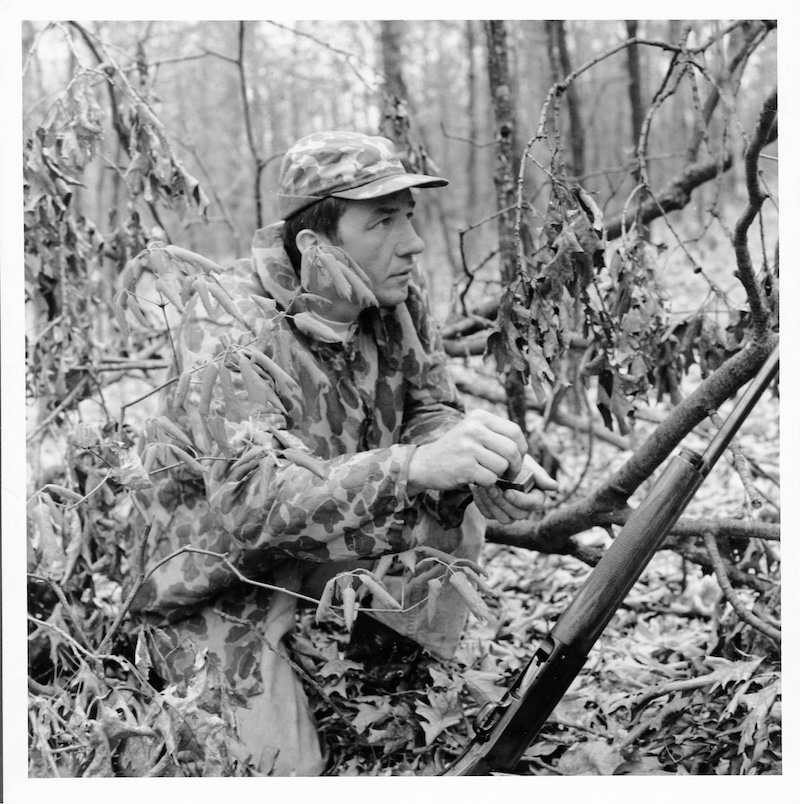

Photo by Alex Galt, USFWS.

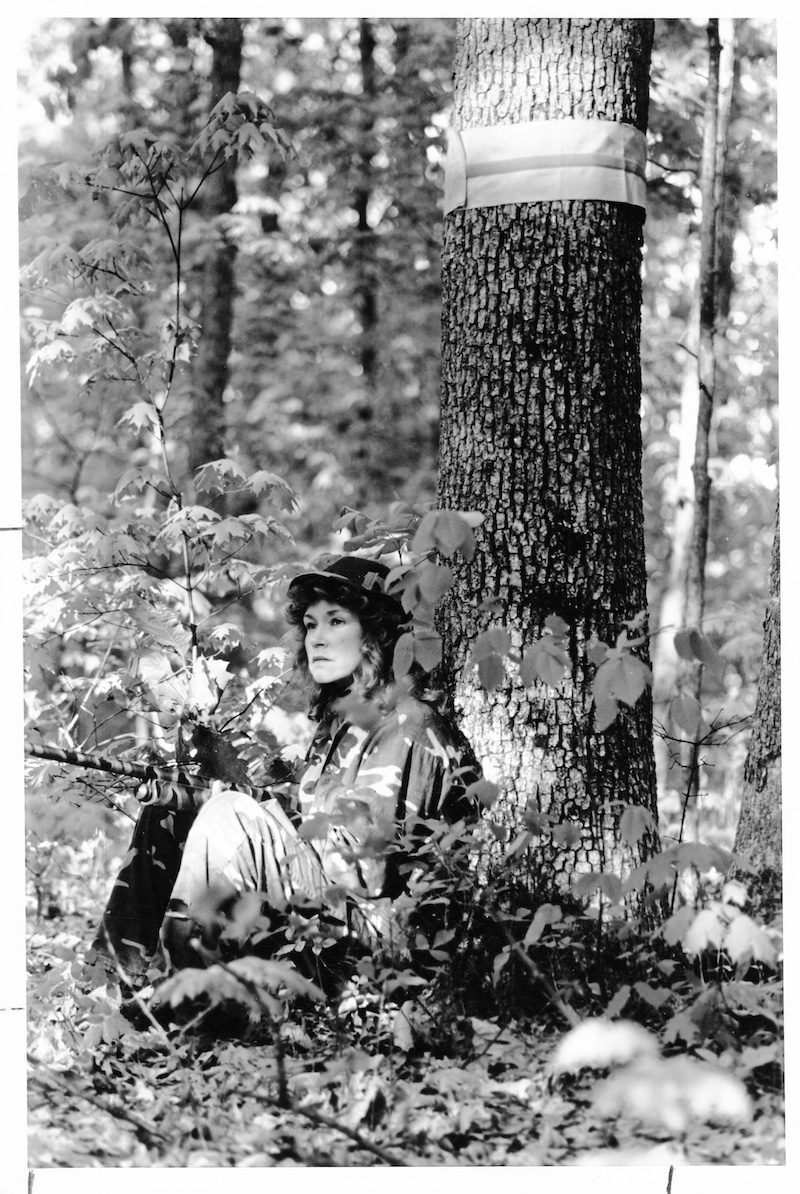

Photo by Alex Galt, USFWS.

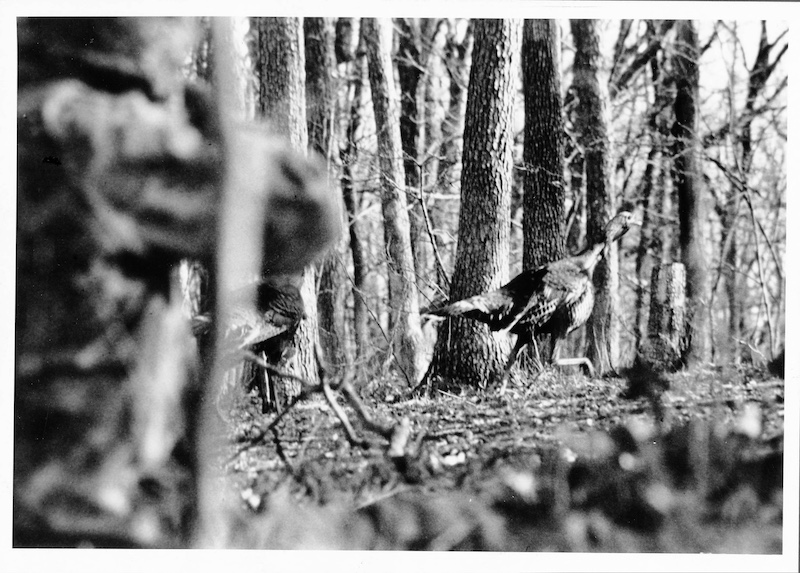

Absent from the 1925 Illinois landscape—the year that the Illinois Department of Conservation, now the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, was formed—were the gobbles, putts and clucks of the eastern wild turkey.

Once abundant, eastern wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo silvestris) numbers had plummeted in the Prairie State to the point that the 1903 Illinois General Assembly closed the hunting season for Illinois’ largest native game bird. That decision was a case of too little, too late. By 1910 turkeys were non-existent in the state. Not until 1970 would the story of the wild turkey take a dramatic turn when the population finally reached a level to support the modern-day hunting season.

The pre-Columbian population of the wild turkey in North America is conservatively estimated to have been approximately 10 million birds. Throughout the 1800s, the need for timber to house and warm settlers and fence-in livestock, coupled with unregulated hunting, took a toll on the wild turkey across much of its range. An estimated 22,000 acres of Illinois’ original 13.8 million acres of forest remained by 1923. Tied to this loss of timber came the extirpation of the wild turkeys, which by 1920 had been eliminated from 18 of the 39 states where they once existed. Turkeys reached their lowest number between 1940 and 1950 when an estimated 39,000 to 200,000 birds existed in North America.

The successful reintroduction of the wild turkey was an effort undertaken by wildlife biologists across the nation. Along the way lessons were learned about the nature of the bird, notably that pen-reared birds were not thriving and reproducing in natural settings. The difficulty of capturing wild birds presented a barrier to reintroductions until the use of rocket-fired cannon nets, a common tool utilized by waterfowl researchers, was proven effective with turkeys. Moving birds across state lines to expand the population hit a snag under regulations of the Lacey Act of 1907 which prohibits the sale and transfer of wildlife. Success was realized when state natural resource biologists began swapping turkeys for other wildlife such as river otters or ruffed grouse, and even bass.

After the 1950s release of pen-reared birds failed in Illinois, like elsewhere, Illinois implemented a trap-and-transplant effort, coordinated by former Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) Wildlife Biologist Jared Garver. Between 1959 and 1967, 65 wild turkeys were captured in Arkansas, Mississippi and West Virginia and released in what was considered prime habitat in five locations in the Shawnee National Forest in southern Illinois. So successful were those initial releases that before long turkeys were being trapped and moved throughout the state.

Between 1970 and 2000 IDNR biologists trapped and transferred more than 4,700 wild turkeys to locations throughout the state. Over time, turkeys were transported to 99 counties. With a typical clutch size per hen is 10 to 12 eggs and a high survival rate it didn’t take long for the wild turkey population to naturally expand into all 102 counties. Within a century, the once extirpated wild turkey now inhabits woodlands and forests in rural and suburban areas across the state.

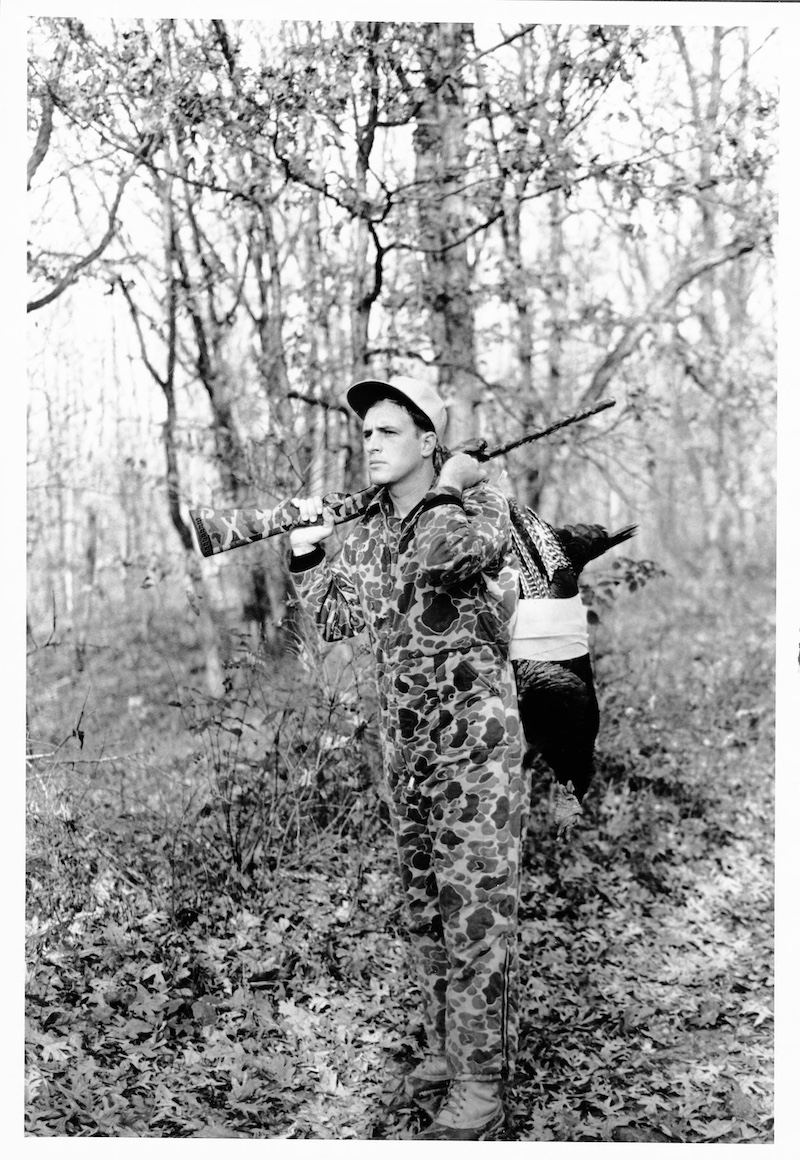

After the initial release of wild turkeys in the early 1960s the wild turkey population quickly became large enough to support a limited hunting season. In the spring of 1970 hunters in three counties—Alexander, Union and Jackson—became the first wild turkey hunters in the state of Illinois in 67 years. That initial season resulted in the harvest of 25 birds. In 1980, two additional counties—Calhoun and Pope—were open to turkey hunting, with 165 gobblers harvested.

The success of the wild turkey recovery effort is evident in the annual hunter harvest numbers. By 2025, a record high 18,189 birds—including birds harvested during the youth season—were harvested during the spring season.

The wildly successful return of the wild turkey to the Prairie State has allowed for expansion of the hunting season. With that came improved hunter success.

The Pittman-Robertson Act (PR) or the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, was established in 1937 and established an excise tax on hunting and shooting equipment, ammunition, and archery gear to fund wildlife conservation and restoration projects in the United States. In Illinois, PR funds have been utilized for research projects to broaden our understanding of the life history and habitat needs of the wild turkey. Funds also have maximized wild turkey habitats on state-owned and -managed lands throughout the state, such as through the development of wildlife openings, watering holes and hunting access roads.

The National Wild Turkey Federation has been a great partner to IDNR in the realization of the recovery of the wild turkey. Among their contributions have been offering boxes for transporting birds, equipment for prescribed burning and prairie establishment, and on-the-ground habitat projects such as the recent efforts at Siloam Springs State Park to prioritize oaks and control exotics within the forest.

Monitoring the presence of wild turkeys on the Illinois landscape has evolved through the years. During the initial years, cooperative landowner brood surveys were conducted and shotgun deer hunters surveyed when checking their harvest in at the then-mandatory check stations. For many years following the advent of the modern turkey hunting season, turkey hunters were questioned at then-mandatory turkey check stations. Among the tools IDNR relies on today are the input provided by volunteer citizen scientists who assist with wild turkey brood surveys.

Luke Garver, Illinois Department of Natural Resources, Division of Wildlife Resources Wild Turkey Project Manager, uses many other metrics to monitor the wild turkey.

“The annual Wild Turkey Survey allows us to monitor the ratios of poults per hen, poults per brood and the male:female ratio,” Garver explained. “We continue to query deer hunters on their turkey observations while they are afield, although today that information is reported online when they submit their deer harvest information. From the online information collected when hunters report their spring turkey harvest we can track hunter success rates and determine trends in the percent of hens and jakes (juvenile males) in harvest.”

In his recent article Monitoring Illinois’ Turkey Population is a Public-Private Partnership Garver also explained how a collaborative effort and development of formal protocols created a system for standardized data collection that today allows wildlife biologists to monitor wild turkey population trends on a multi-state and regional basis.

Besides the false start and recognition that pen-raised wild turkeys would not survive in nature, a broader understanding of the wild turkey has developed among wildlife biologists throughout the nation.

Once upon a time it was believed that wild turkeys needed 50,000 acres of remote forest to survive. Today we know that is not true. It is not uncommon to see turkeys, or their sign, as you travel about in local state parks or conservation areas. Or catch sight of birds feeding on waste grain in an agricultural field in the early spring with tom turkeys strutting before attendant hens. The growing population also means on a spring day, residents in suburban areas can experience the gobbles, clucks and putts of a turkey flock passing through their neighborhood.

“Thanks to decades of restoration work and the ongoing commitment of hunters, landowners and conservation partners, Illinois now has a healthy, sustainable wild turkey population,” Garver concluded. “Our focus today is on monitoring data trends and habitat management to ensure the wild turkey resource persists for generations. We’ve had success with wild turkey restoration, but conservation is never finished.”

Kathy Andrews Wright retired from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources where she was editor of OutdoorIllinois magazine. She is currently the editor of OutdoorIllinois Journal.

Submit a question for the author

Question: Hi Kathy,

I am a master’s student at SIUC working on a wild turkey gobbling chronology project with Brent Pease and Luke Garver. I think the timeline of opening up the state to hunting is something I would like to include in my thesis, and I was wondering if you knew when the north and south management zones for wild turkey were introduced in IL? Was it in 2013 when all 100 counties besides Cook and DuPage counties were open? Any insight and reading materials would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you!

Lucy Cheeley

lucille.cheeley@siu.edu