Have you ever been surfing social media and come across a viral video of a person feeding human food to a wild animal? These videos seem to be everywhere on the internet, and they are a big hit. The beautiful deer or the little duck is just too cute to resist. People may put food out for wildlife during the long cold winters thinking they are helping wildlife survive, but that is almost never necessary. Some hunters, photographers and wildlife enthusiasts may put out bait piles or salt licks to make the deer hunt easier, increase the chances for a photo, or in the mistaken belief that deer need help meeting nutritional requirements. These actions may appear harmless at the time, but feeding wildlife is damaging and putting out food or bait for deer is prohibited by both Wildlife Code (520 ILCS 5/2.26) and Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) Administrative Rule 17-635.

The feeding and baiting of wildlife, especially deer, causes a downward spiral of events that may significantly damage the wildlife population. When humans feed wildlife, wildlife may become habituated to and dependent on humans for food, rather than foraging for healthier, natural food. It may be tempting to feed deer, especially in the winter, when you think it is more difficult for a deer to find food, but a deer’s digestion and metabolism become well adapted to the food naturally available to them. Occasionally feeding deer foods that they are not used to can change their metabolism, making it harder to process their natural food and causing them to burn essential fat faster. It can actually lead to starvation instead of helping. Continued feeding leads to habituated deer that are aggressive and demanding, which turns them into a domesticated nuisance. The deer become less afraid of humans and regularly return to a feeding site seeking more food. Habituated deer can be a danger to humans from increased risk of deer-vehicle collisions and even direct attacks on humans.

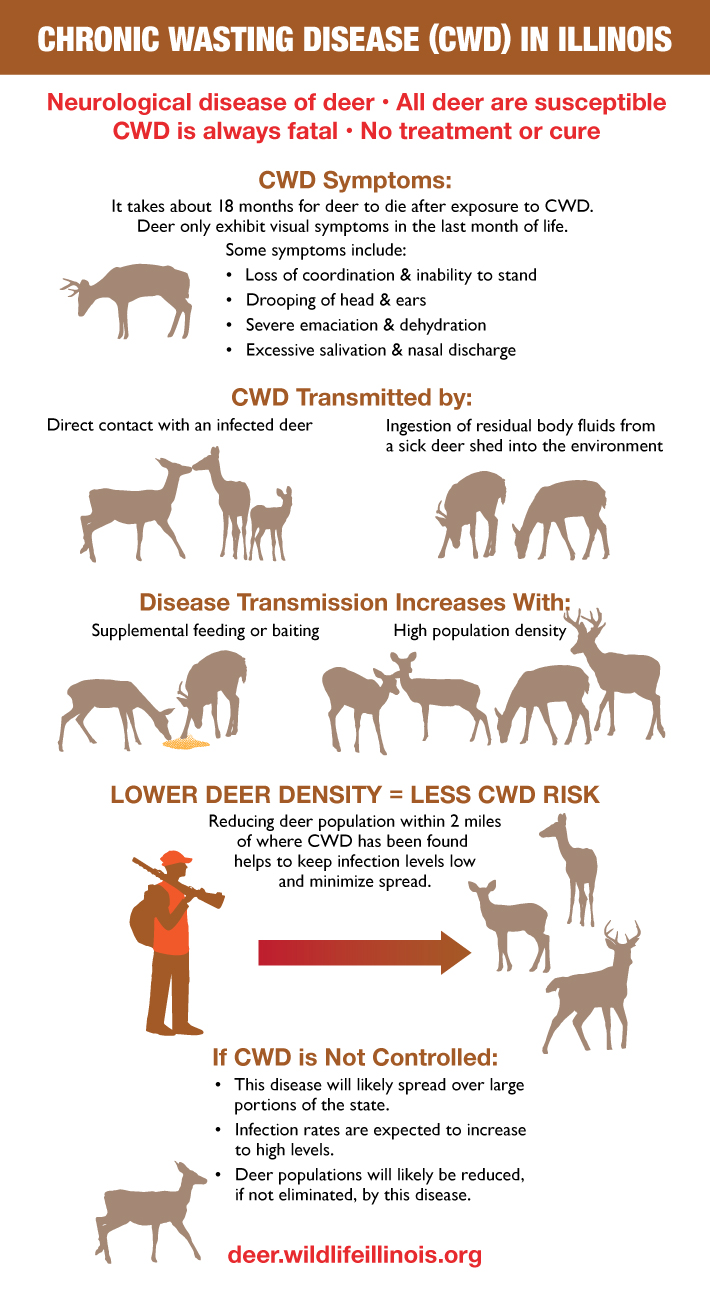

Feeding and habituating deer also favors unnaturally large congregations of wildlife in one area. Deer normally live in small groups, naturally practicing “social distancing.” Large gatherings of animals at a feeding site significantly increases the risk for disease transmission. This is perhaps the most significant threat that the feeding and baiting of deer poses.

Close contact with other deer increases direct and indirect transmission of infectious diseases. Direct transmission of diseases may occur when an infected deer is at the same feeding site as a healthy deer. For example, Bovine Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious bacterial disease that is spread through respiratory droplets. If a deer infected with Bovine TB joins a gathering of deer at a feed site, the disease is easily transmissible to the healthy deer (direct transmission). Indirect transmission may also occur as the bacteria that causes Bovine TB, Mycobacterium bovis, can live on a frozen feed pile for up to 16 weeks. The bacterium’s prolonged survival on a feed pile allows one infected deer to potentially infect every healthy deer eating there weeks later.

Chronic Wasting Disease, or CWD, is another disease that poses a considerable risk to the health of the deer herd, and feed piles serve to spread CWD from one animal to the other. CWD is an unusual pathogen, caused by an infectious protein, and capable of causing a 100 percent fatality rate in deer. This disease causes a slow degeneration of the brain that results in severe emaciation, abnormal behaviors and ultimately death. Transmission of CWD occurs through direct contact with the saliva, feces, blood or urine of an infected deer.

CWD prions are also able to persist in the soil for years. Thus transmission, as in the case of TB, can occur both directly and indirectly.

CWD poses a significant threat to cervid species due to the difficulty in controlling the disease and the lack of treatment or vaccine. Feeding or baiting deer make it easier for this infectious protein to spread from sick to healthy animals because of the high densities of deer congregating in one small area. Occurrences of these large congregations of deer can be significantly reduced if supplementary baiting and feeding are banned. Such a ban already exists in many U.S. states, Illinois included, as well as in Norway. Fortunately, many Illinois landowners and hunters are adamantly opposed to feeding and baiting, and fully abide by the ban set by IDNR. The ban can decrease the likelihood of an infectious deer having direct or indirect contact with a healthy deer, which is critical in controlling both CWD and Bovine TB.

Indirectly, feeding and baiting of wildlife also pose threats to human and livestock health. Bovine Tuberculosis, for example, is transmissible from deer to livestock and humans. While it is currently unknown if CWD can be transmitted to humans or livestock, it is vital to prevent the spread of CWD among animals. This may reduce the risks of human exposure to the CWD-prion until more conclusive scientific evidence states that CWD is unlikely to pose a threat to humans.

Wildlife are naturally provided with the tools to forage on their own and to find the resources and nutrition metabolically required. They have the physiological ability to survive long, cold winters without the help of humans. Science has demonstrated this time and again. Feeding and baiting may seem harmless or even benevolent at times. However, the brief moments of joy a person experiences from feeding wildlife do not outweigh the damage and long-term impacts on the population. Simply leaving wildlife alone and supporting the persistence of natural habitats and ecosystems, is a far better way of caring for wildlife than any amount of feeding can do.

References

Fortin, Nick, et al. The Outside Story Feeding Deer Does Much Harm.

Inslerman, Robert A., et al. “Baiting and Supplemental Feeding of Game Wildlife Species.” The Wildlife Society. Technical Review, December, 2006, p. 59.

Mysterud, Atle, et al. “Legal Regulation of Supplementary Cervid Feeding Facing Chronic Wasting Disease.” Journal of Wildlife Management, vol. 83, no. 8, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2019, pp. 1667–75, doi:10.1002/jwmg.21746.

Rivera NA, Brandt AL, Novakofski JE, Mateus-Pinilla NE. Chronic Wasting Disease In Cervids: Prevalence, Impact And Management Strategies. Vet Med (Auckl). 2019; 10:123-139, https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S197404

Sorensen, Anja, et al. “Impacts of Wildlife Baiting and Supplemental Feeding on Infectious Disease Transmission Risk: A Synthesis of Knowledge.” Preventive Veterinary Medicine, vol. 113, no. 4, Elsevier BV, 2014, pp. 356–63, doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.11.010.

Wildlife, Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Fish and. Feeding Deer: Just Say No.

Kelsey Martin is a recent graduate of the Department of Animal Sciences at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and is a member of the Novakofski and Mateus Chronic Wasting Disease research lab.

Dr. Nohra Mateus-Pinilla is a veterinary Epidemiologist working in wildlife diseases, conservation, and zoonoses. She studies Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) transmission and control strategies to protect the free-ranging deer herd’s health. Dr. Mateus works at the Illinois Natural History Survey- University of Illinois. She earned her M.S. and Ph.D. from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Dr. Jan Novakofski studies prion diseases or infectious agents composed entirely of protein in animals such as “mad cow disease” and scrapie. His efforts are contributing to better understanding the genetics and transmission of these types of diseases to protect the health of animals and humans. He earned his B.S., M.S. and PhD from the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Dr. Nelda Rivera's research focuses on the ecology and evolution of new and re-emerging infectious diseases and the epidemiology of infectious diseases, disease surveillance, and reservoir hosts’ determination. She is a member of the Wildlife Veterinary Epidemiology Laboratory and the Novakofski & Mateus Chronic Wasting Disease Collaborative Labs. She earned her M.S. at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and D.V.M at the University of Panamá, Republic of Panamá.

Submit a question for the author