The four species of invasive carp are notorious for their negative impacts on native ecosystems–and for their habit of jumping into boats. All photos courtesy of the authors.

The four species of invasive carp are notorious for their negative impacts on native ecosystems–and for their habit of jumping into boats. All photos courtesy of the authors.

How much impact are we having on invasive carp in the Illinois River? Where are they and how are their populations shifting? Are removal efforts helping native fish and ecosystems? These are a few of the many questions the Multi-Agency Monitoring program is designed to answer!

Over the past few decades, invasive carps have become the most infamous invasive species in the United States. These four species — bighead carp, silver carp, black carp and grass carp — are notorious for their negative impacts on native ecosystems. From jumping into boats to vacuuming up tiny plankton that form the base of the food chain, these fishes are leaving a lasting impact on Illinois waters, but fisheries scientists are working tirelessly to fight this invasion.

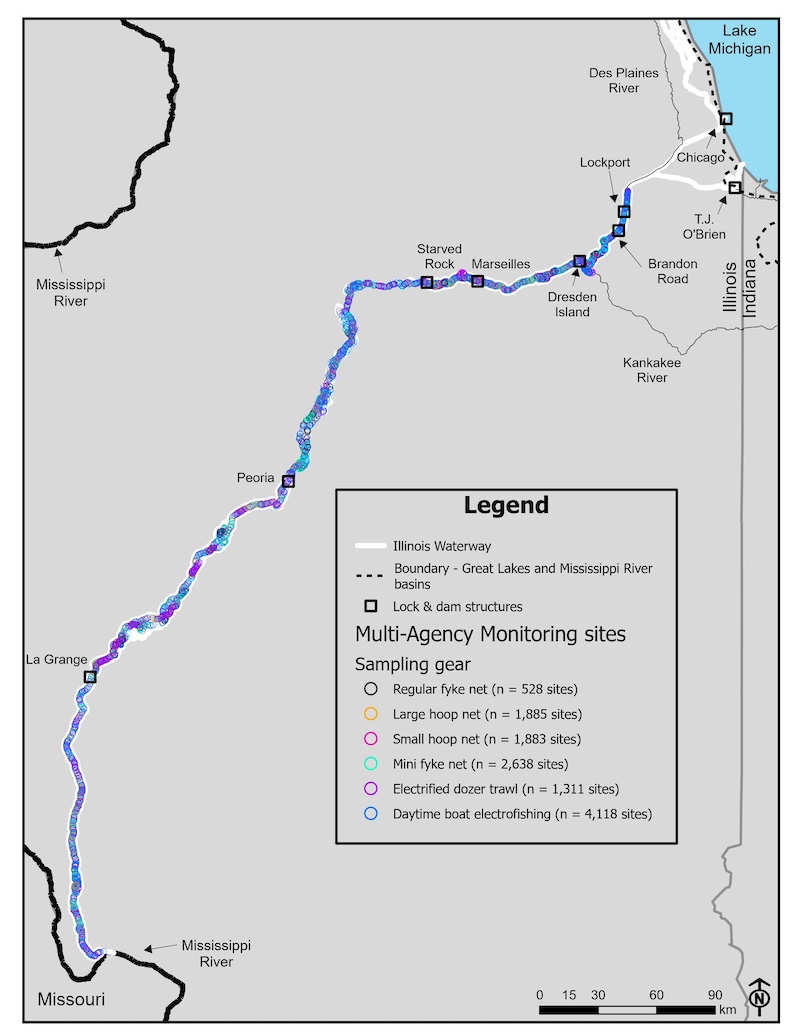

The state of Illinois has the only complete connection between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Basin via the Illinois Waterway, which is comprised of the Chicago Area Waterway System, portions of the Des Plaines River, and the entire length of the Illinois River. To fight back against this invasion and prevent the spread of invasive carps into the Great Lakes, intensive Illinois Department of Natural Resources-led contracted and commercial harvest programs have been implemented to reduce invasive carp populations. In conjunction with harvest, a partnership of state and federal agencies and universities intensively monitors to track adult and young-of-year invasive carp abundance throughout the waterway.

To better inform invasive carp control and understand the Illinois Waterway fish community, the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS) and Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) formed the Multi-Agency Monitoring program, also called MAM, in 2019. This program brought together regional partner agencies such as U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, IDNR, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and INHS.

The program built upon existing long-term monitoring on the waterway, including the Upper Mississippi River Restoration Program’s Long Term Resource Monitoring element and the Long-Term Survey and Assessment of Large-River Fishes in Illinois program. The Long Term Resource Monitoring fish sampling framework uses a statistically robust, multi-habitat (main channel, side channel and backwater), multi-gear (fyke nets and hoop nets, boat electrofishing), random (probabilistic selection of sites) sampling approach that can detect shifts in fish abundance and community composition. The large river fishes assessment also follows these sampling protocols.

The MAM program’s regional partnership broadens the existing standardized sampling framework to encompass nearly 300 river miles of the waterway (approximately 2,400 sites), stretching from above the Lockport Lock & Dam near Lockport, to the confluence of the waterway and Mississippi River near Grafton.

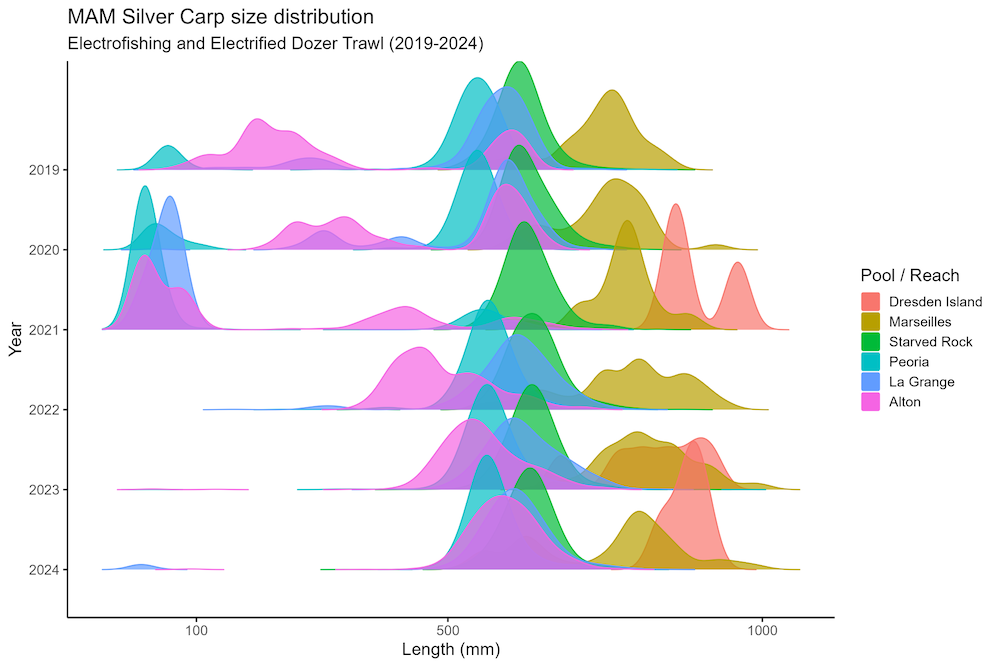

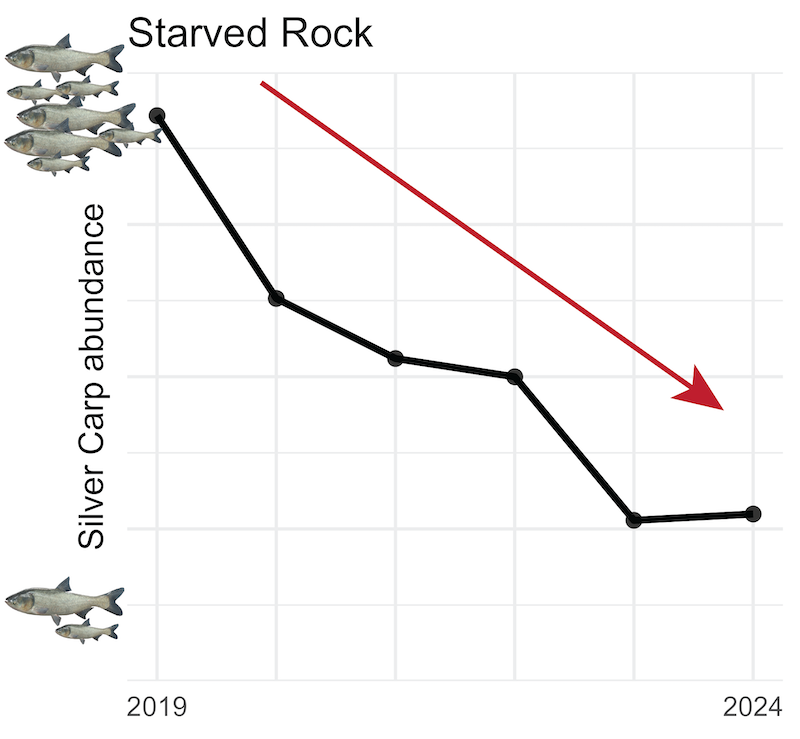

The program is a powerful collaborative resource for tracking the abundance and recruitment (presence of young-of-year individuals) of invasive carps and serves as the foundation for evaluating the success of invasive carp management programs such as commercial harvest. Contracted harvest by experienced fishermen and incentive- and market-driven commercial harvest of invasive carps is a key management tool, but the number of carp removed each year is not a reliable indicator of how many carp are out there. Commercial fishers are extremely efficient at removing carp, finding ways to keep harvest high even as carp populations decrease. The MAM program leverages statistics and standardized sampling to provide unbiased estimates of invasive carp abundance necessary to assess the effectiveness of harvest in each pool of the Illinois Waterway.

Since its inception, the program has demonstrated the success of removal efforts and reductions in invasive carp in the upper three reaches of the waterway over the past six years — thus, reducing pressure and challenges to the electric dispersal barrier and Lake Michigan and improving our native fishery. The program catches all kinds of fish — not just invasive carps – and the abundance and condition (i.e., how ‘fat’ or ‘skinny’ a fish is) of native fishes, such as channel catfish or bluegill, can be indicators of the impact invasive carps have on the ecosystem. When native fishes must compete for food with invasive carps, they get skinnier. Tracking trends in the condition of our native fishes can be a good indicator of not just how many invasive carp are in the river, but their direct impacts on the ecological function of the ecosystem.

Reducing invasive carp abundances to the extent that their impacts to natives are negligible and returning our native fishes to healthy benchmarks for abundance and condition can be a tractable goal for river managers to pursue. Early detection monitoring of invasive carp seeks to detect young-of-year and adult invasive carps in areas where they have not been detected in the upper Illinois River and Chicago Area Waterway System, and the MAM program also serves the added role of improving early detection monitoring for all life stages of invasive carp where they haven’t been detected yet by recommending the optimal gear to use in specific areas based on sampling in the lower pool where all life stages are present.

The program’s success and powerful framework allow us to keep score in the fight against invasive carp — and to adapt as the invasion demands. As the IDNR continues to improve efficiency and effectiveness of harvest, MAM provides the barometer to evaluate success. It draws its strength and inferential power not only from its strategic, standardized, and robust design, but also the strengths and resources of coordinated multi-agency partnership within Illinois and with our Great Lakes neighbors.

Brandon Harris is an Associate Large River Fisheries Ecologist at the Illinois River Biological Station – Illinois Natural History Survey. His research focuses on using monitoring data from the Illinois River Waterway to inform invasive carp management decisions and to assess the impact of invasive carps on native fishes.

Michael Spear is a quantitative ecologist at the Illinois River Biological Station. His work leverages statistics and computer programming to help fellow scientists and natural resource managers make data-driven decisions. A resident of La Grange Park, Spear proudly works to protect Illinois’ rivers on behalf of the communities through which they flow.

Jim Lamer is an associate large river ecologist and Director of the Illinois River Biological Station at the Illinois Natural History Survey, specializing in aquatic resource monitoring and management. His research focuses on understanding the dynamics of native and invasive species within large river systems to inform sustainable management practices and understand long term drivers of system change.

Andrya Whitten Harris is a Large River Fisheries Ecologist for the Illinois Natural History Survey at the Illinois River Biological Station in Havana. Her research focuses broadly on freshwater fish ecology, with the main area of research on the Illinois Waterway. She is currently working on leveraging long-term data sets to describe the distribution, relative abundance, and detection frequency of non-native and native fishes in Illinois.

Submit a question for the author