Stiltgass sometimes carpets forest understories, outcompeting native vegetation. Photo by Chris Evans, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Emerging Invasive Plants in Illinois

Invasive species are often hugely problematic in forestry and natural resource management. Problems range from tree seedling suppression and overall exclusion of native species seen in areas severely invaded with species, such as stiltgrass, or even the near annihilation of entire genera, as is occurring with our ash tree species confronted by the emerald ash borer invasion. When invasive species become ubiquitous on the landscape, control efforts shift goals from total eradication to containment or sometimes localized control in certain areas. We want to avoid that situation, so early detection of potentially invasive species offers us the best chance of eradication or suppression requiring fewer resources over time.

Early Detection, Rapid Response

One of the most effective actions people can take in combating invasive species is called Early Detection, Rapid Response, or EDRR. EDRR is most effective when a new invader is recognized early in the invasion. It is quickly dealt with to eradicate the population before it becomes so widespread that eradication is extremely difficult or impossible. One way to improve our early detection capabilities is to review new invaders that may be coming to our area from elsewhere. While the species I’m about to introduce are already problematic on the landscape more broadly, early detection and rapid response in places where they are not yet widespread can reduce the overall negative effects and costs of these invaders in regions where they have yet to gain a foothold.

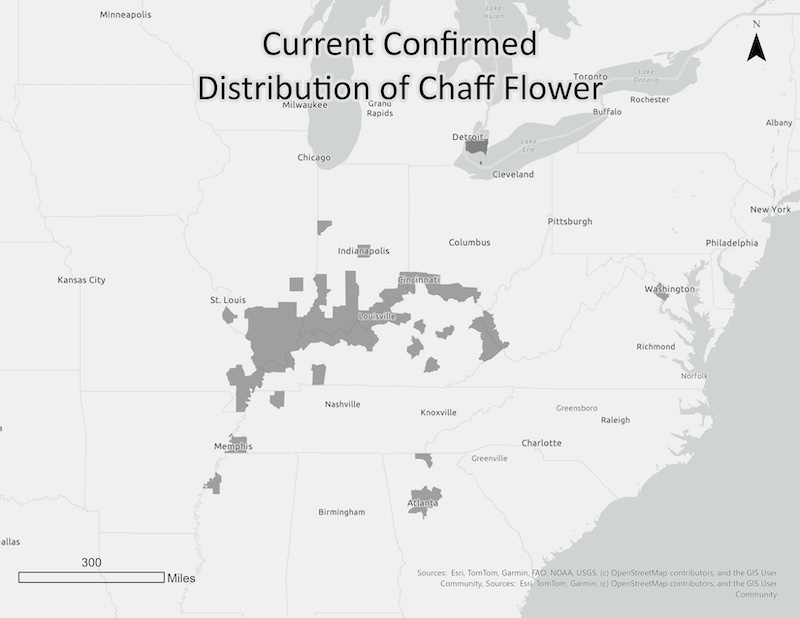

Chaff Flower

In recent years, one of the most problematic invasive plants in Illinois is chaff flower, aka Japanese chaff flower (Achyranthes japonica). Chaff flower is an herbaceous perennial that tolerates a wide range of conditions but thrives in moist forested areas, tree plantations, forest edges, landscaping and some open areas. Chaff flower originates from east Asia and was first found in North America in 1980 in eastern Kentucky. It has been spreading along the Ohio River valley ever since. While there is no specific evidence of how it reached this area, it has been used in traditional medicine and may have been intentionally introduced in gardens.

Unfortunately, however, chaff flower rapidly spread once it arrived. Chaff flower shares many characteristics with other invasive plants, such as producing prolific amounts of seed and dispersing easily. Chaff flower seeds disperse through water along rivers and streams, and cling to people’s clothing and shoelaces, animal fur, and bird feathers. The spread of propagules by animals is called zoochory. For example, it is a common dispersal category among plants such as cockleburs or tickseed that stick to our clothing. Chaff flower is rapidly expanding its range now through those mechanisms.

In Illinois it is primarily found in southern Illinois but could be found anywhere throughout the state by hitching a ride on people’s clothing, footwear, or other gear, animal fur, or even bird feathers.

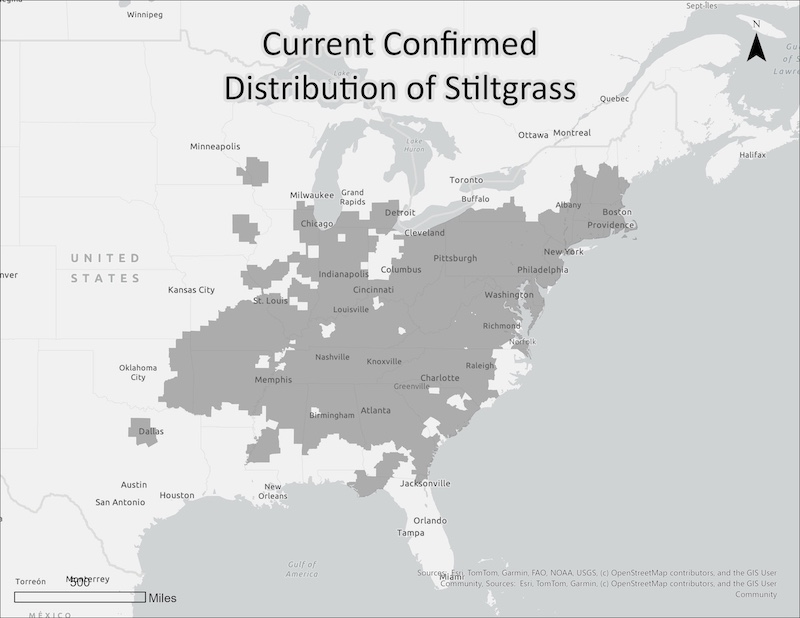

Stiltgrass

Another species in the forest understory that has been around southern Illinois for a more extended period but is expanding its range into central and northern Illinois is stiltgrass, or Japanese stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum). Stiltgrass was first documented in Tennessee in 1919 and likely arrived from east Asia as packing material in shipping. It often gets around as a tiny seed in people’s muddy equipment and footwear and by mowers dragging seed along trails and roadsides. Some birds, such as turkeys, have been found to consume the seed, but it is unknown if the seeds are viable after consumption and if they spread in that way. Stiltgrass is an annual shade-tolerant grass that, once established, can carpet an understory, outcompete native species and change fire intensities, leading to more changes in vegetation communities.

Some studies found that infested areas resulted in reduced tree seedling survival (e.g. Flory et al 2015). In contrast, others found little difference in tree survival in longer-term studies (Flory et al. 2017). Hence, the effects of stiltgrass on forest regeneration are unclear. Stiltgrass also changes wildlife habitat in ways we do not fully understand. For example, one study found areas invaded with stiltgrass had higher populations of wolf spiders that predated toads, leading to reduced toad populations and likely other prey species (DeVore and Maerz 2014). We still have much to learn about invasion ecology and the overall implications of these problematic species.

Amur Corktree

Amur corktree (Phellodendron amurense) is another invasive plant making troublesome inroads across Illinois and beyond. Corktrees were introduced initially as arboretum specimens and ornamental trees in the mid-1800s.

Amur corktree is a deciduous tree with compound leaves that may, at first glance, resemble those of an ash tree. The bark is distinctive, corky with bright yellow inner bark, and developing thick, spongy and corky bark as it matures. The fruits are round and green and turn black in winter. The fruits are eaten and spread by birds, thereby spreading their seeds. Each tree can produce thousands of seeds. This species has often been found in forest gaps and edges and was noticed to have filled in many forest gaps originating from the derecho of 2009 in southernmost Illinois.

Additional Invasive Plants of Concern

These are just a few of the emerging invasive species in Illinois. Some other species of concern include wineberry (Rubus phoenicolasius), Amur maple (Acer ginnala), European cranberry bush (Viburnum opulus var. opulus), tree lilac (Syringa reticulata), jetbead (Rhodotypos scandens) and others.

You may be asking, ‘What can I do to help?’ First, choose native plants for landscaping. Many invasive plants start out as landscape plants that become invasive following a lag phase.

Many invasive species occur in and around Illinois that we would benefit from catching earlier in the invasion process. If you see any of these species in areas outside of their known range, please report them. Invasive plants are easily reported through EDDMapS or iNaturalist so land managers and researchers can track their spread and adjust management strategies.

For more emerging invasives to look for, see the Midwest Invasive Plant Network webpage and for more information on these species, visit the Illinois Extension website on invasive species.

References

DeVore, J. L., & Maerz, J. C. (2014). Grass invasion increases top‐down pressure on an amphibian via structurally mediated effects on an intraguild predator. Ecology, 95(7), 1724-1730.

EDDMapS. 2025. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia – Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online at http://www.eddmaps.org/; last accessed June 26, 2025.

Flory, S. L., Clay, K., Emery, S. M., Robb, J. R., & Winters, B. (2015). Fire and non‐native grass invasion interact to suppress tree regeneration in temperate deciduous forests. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(4), 992-1000.

Flory, S. L., Bauer, J., Phillips, R. P., & Clay, K. (2017). Effects of a non‐native grass invasion decline over time. Journal of Ecology, 105(6), 1475-1484.

Rohling, K. (2017). Ecology and control of Amur corktree [Fact sheet]. River to River Cooperative Weed Management Area.

Kevin Rohling serves as an Extension Specialist in Forest Management and Ecology with the University of Illinois Extension Forestry, where he leads research initiatives and educational programs. He holds both B.S. and M.S. degrees in Geography from Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, with a focus on Biogeography and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Since 2004, Rohling has been actively involved in natural resource conservation. His professional interests include forest ecology, invasive species management, the application of technology in forestry, prescribed fire, wildlife, chainsaw safety, natural areas management, and public outreach and interpretation.

Submit a question for the author

Question: I have 20 acres of mixed hardwood in Cumberland County. There is a lot of bush honeysuckle that I’m trying to get under control. I notice the deer browsing on it a lot after most of the other underbrush is dormant. How much nutritional value does it have, or is it just filling the void?

As I clear a spot, what, if anything, should I replace it with?

Question: How to kill Chinese Fountain Grass. I think it was supposed to be ornamental, but now has become a problem for landowner in Johnson co.

Please advise

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Explore Our Family of Websites

Similar Reads

Need Landscaping Advice? Ask a Friend!

February 2, 2026 by Kathy Andrews Wright

An Accessible Alternative to Honeysuckle Management and Woodland Restoration

February 2, 2026 by Justin J. Shew, Addis Moore

Tiny Threatened Fish Species Re-introduced for the First Time

February 2, 2026 by Hugh Gabriel

Winter Weather Effects On Northern Bobwhite in Illinois

February 2, 2026 by John Cole

A Prairie Imagined

February 2, 2026 by Patty Gillespie

To Manage or Not to Manage: Primary nesting season and what it means

February 2, 2026 by Heather Herakovich

Remembering John L. Roseberry

November 3, 2025 by John Cole

A Wild (Turkey) Century of Recovery

November 3, 2025 by Kathy Andrews Wright

Scientific Outreach with a Fantasy Twist: Using costumes and role play to teach principles of invasion biology

August 1, 2025 by Philip Anderson

Be a Hero—Transport Zero

August 1, 2025 by Kevin Irons, Brian Schoenung