An infestation of sericea lespedeza. Photo by Richard Gardner, Bugwood.org.

An Invasive Species that Spreads Like Wildfire: Sericea lespedeza

The sun beats down on a warm spring day that feels more like summer as I walk along the edge of a pollinator field, taking stock of the diversity of flowers and grasses present. Up ahead, I notice a cluster of plants that looks a bit different than the surrounding vegetation. My heart sinks as I make my way toward them. “Please don’t be what I think it is…” I say to myself until I get close enough to see that it is in fact what I think it is. I let out a heavy sigh and take in the beauty of the rest of the field where this plant hasn’t yet spread and wonder how long until it does.

In my role as a land conservation specialist, I am fortunate to have the opportunity to speak with numerous landowners throughout central Illinois. A common theme in our conversations is invasive species. Many times, a landowner knows what they have on their property and is actively working to manage the land. However, I often find myself pointing out one plant that a lot of folks have never heard of: sericea lespedeza.

History

Sericea is a type of legume, or clover, native to Asia. Some other common names include Chinese or silky bush clover. It was introduced to America in the early 1900s, planted intentionally as grazing forage and to control erosion. It also was planted by many land managers as a food source for upland birds, but the tough seed coat makes the seeds highly undigestible. Birds do readily consume the seeds and deposit the undigested, viable seeds across the landscape, adding to the spread of sericea. There were even publications during the 1950s describing the benefits and how to best get sericea established in fields. But hindsight is 20/20, and by the time folks realized that it spreads like wildfire and quickly becomes too woody for livestock to graze, the damage was done. Sericea was established and has since been working its way across the landscape.

Prolific Producer

There are numerous tactics plants use to spread, and this one uses just about every trick in the book. Prolific seed production is an obvious method. While sometimes remaining a single shoot, seedlings begin developing branches at roughly 8 weeks of age and every one of those branches can produce upwards of 1,000 seeds! Top it off with the fact that those seeds can remain viable in the soil for upwards of 20 years, and it becomes evident how vigorously sericea infiltrates the seed bank.

Branches

The branches themselves also create a problem for neighboring plants. Typically standing 3 to 5 feet tall, the numerous branching arms of sericea easily starve many of our native forbs and young grasses of the sunlight they need. Within the first three years of life, a plant can have as many as 20 to 30 branches. One study found up to a 70 percent loss of native plants when branch counts exceeded 352 per square meter (Blocksome, 2006).

Production of a Toxin

Altering the soil is another way sericea survives. Known as allelopathy, the roots release a toxin into the soil that inhibits the growth of nearby plants. Numerous plants have this ability, and it is not inherently negative—think of marigolds deterring pests in vegetable gardens. Allelopathic compounds from leaves, stems, and roots of sericea have been shown to hurt the germination of desirable prairie grasses such as big bluestem and Indian grass (Dudley and Fick, 2003). Another study found a loss of up to 24 percent of forage production in bermudagrass and other pasture grasses.

Sericea is a Water Hog

As if all of that weren’t enough, sericea is a water hog. While it is drought tolerant (another trait helping it spread in North America), sericea requires more water than native species. It is less efficient utilizing water, meaning it needs more water for the same level of production as its counterparts. To account for this increased need, deep tap roots are utilized to reach deeper stores and take up more water when rain occurs.

Above ground, sericea grows rapidly, producing numerous branches on each plant, allowing it to shade out neighboring plants and produce a massive number of seeds every season. Below ground, it outcompetes neighboring plants by beating them to water and releasing chemicals to stunt growth and harm germination. This plant has an advantage on all sides. Biologically, it’s almost impressive…almost.

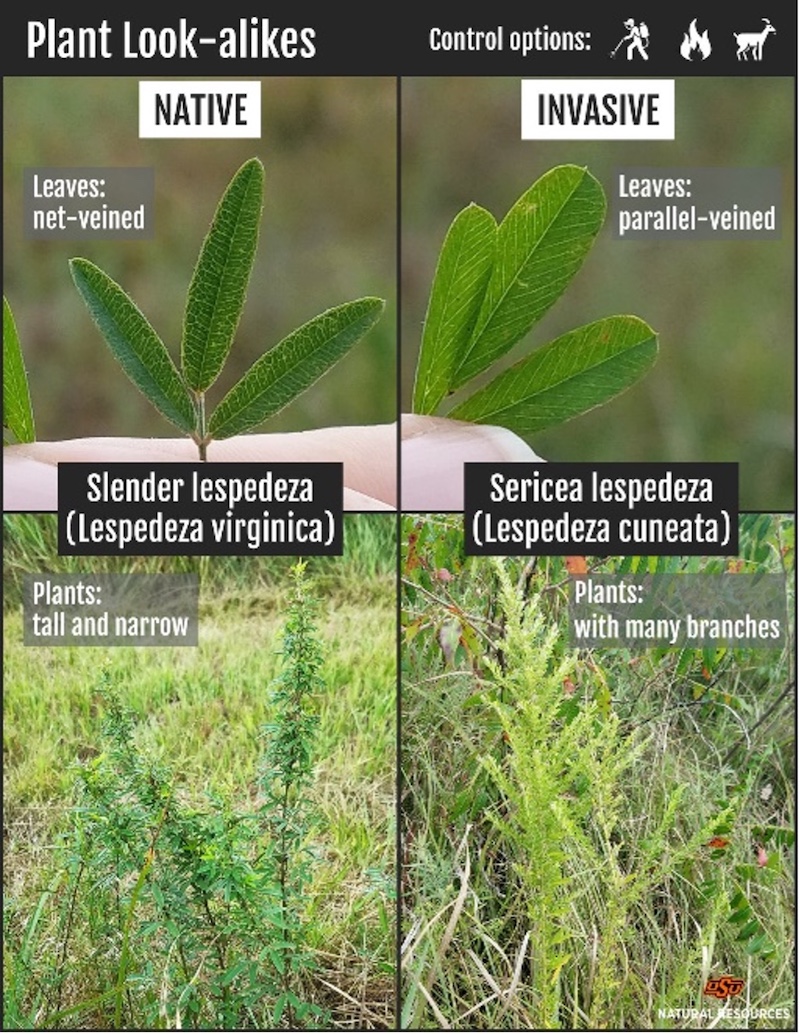

Look Alike

It is worth noting that sericea blends in by appearing to be one of the locals. Most invasive plants have a native counterpart. Typically, there’s already a plant that is serving a similar role in the ecosystem (i.e. vine, floating plant, etc.) and likely looks very similar. In this case, there is a legume that calls north America home, slender lespedeza (Lespedeza virginica). It can be difficult to differentiate, but knowing a few traits to look for makes it easier to identify and locate the invasive sericea. Both have small leaflets of three (a key clover characteristic) but their veins are different. The veins of the introduced sericea are straight, parallel and run to the edge of the leaf; the veins of the native lespedeza have more webbing and tend to curve near the edge of the leaf. Flowers of the invasive sericea are creamy white with purple-blue stripes inside; our native lespedeza boasts flowers that are pink-purple. And remember all those branches sericea puts out? Native lespedezas tend to be tall slender stalks without the branches.

Controlling Sericea

The speed with which sericea can become the dominant species is staggering. How do we fight back? Sericea has many tools for survival, but we have multiple tools in our toolbox of management methods as well. With every property being unique, there is no cookie cutter solution, but it will require a combination of methods and an investment of time over several years.

- Hand pulling is an option, but given the deep tap roots, it’s not a great option. If plants can be pulled during the first year before reaching about 12 inches tall, it’s doable. But bear in mind those roots grow fast and failing to get the entire root will lead to regrowth. I personally would spare my back and instead opt for mowing or cutting.

- Mowing is going to be an important tool in this fight. Mowing will stunt growth and prevent seed production, but it needs to be done within a certain time frame. Studies have shown mowing when plants reach 12 to 18 inches tall, after herbicide application, and mid-summer during flowering are effective to stunt growth (Farris, 2006; Fuhlendorf et al., 2017). The goal is to prevent seed production.

- Burning is also a method many folks turn to for control of weeds. It is important to know that burning alone will make the issue worse in this case. Sericea seeds have an extremely tough coating. Fire cracks this seed coat which allows for germination. This can be a useful tool to deplete the seed bank faster. However, burning by itself is akin to cutting a head off a hydra. More will come after the attack, so only burn if you are prepared to use other methods when the seedlings emerge. Spring burns are common, however, there is a growing amount of evidence showing late grow-season burns (throughout September) to be more impactful.

- Herbicide is another important tool in our arsenal. Carefully following all herbicide labels and instructions, you’ll want to choose a broadleaf spray. Studies have found the best results with triclopyr and even better results with a mix of triclopyr and fluoxypyr (Pheasants Forever, 2025; Farris, 2006; Fuhlendorf et al., 2017). The two chemicals affect the plants via different methods, putting more stress on the plant and providing a higher rate of kill. Again, timing is everything. A pre-emergent herbicide can be applied early in the year – a great option to follow a fall burn. During the growing season, the best time to spray is late summer during budding and early flower formation. Late application after flowering will kill the plant, but viable seeds may still be produced, so make sure to apply herbicide early enough to prevent seed development.

- A combination of methods utilized over several years is going to be key. Burning in the spring can help clear out old vegetation, allowing for better detection and coverage when spraying regrowth. Fall burns weaken the adult plants before a stressful winter season and destroy flowers and developing seeds at a point in the year where there likely won’t be enough time for regeneration. Follow burning with spraying as new growth emerges and then spot mow or trim as the season continues. Alternate spraying and mowing throughout the season, ensuring the plants get mowed before seeds can be formed. One study found cutting seedlings before branching occurs (approximately 7-8 weeks) can be especially effective, particularly for folks who may not wish to use chemicals (Farris, 2006). Regardless of what combination works best for your situation, it is going to be a long battle. Treatment will need to continue over several years, especially in areas where plants are thick. Sericea is a persistent plant, we need to be even more persistent in our pursuit of eradication.

Looking Forward

Invasive species become established because they are unknown by most land managers and they go undetected for some period of time. Sericea is no different in this regard. Let’s take a page from the book of invasion ecology – let’s be just as persistent and spread awareness! Talking to your neighbors, family, friends and anyone who listens can go a long way. Awareness of an issue is a critical first step in addressing it.

Even if you don’t have sericea on your property, something you can do is report sightings of invasive species (of any kind). Doing this contributes to citizen science by adding to distribution maps and assisting with early detection. The website also provides current species distribution maps and information. This tool allows you to see where different species have been reported and share with others what you have encountered.

Looking at fields where sericea is creeping in or already taking over can be disheartening, but I can’t help but have hope. As Dr. Suess famously said “until someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing’s going to get better. It’s not.” I do care a whole awful lot, and I have met many landowners and conservationists who also care a whole awful lot.

Working together, one property, one field, one plant at a time, we can keep invasive species under control and provide beautiful functional habitat for wildlife.

References

Sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata): Seed dispersal, monitoring, and effect on species richness (Carolyn E. Baldwin Blocksome, 2006)

Effects of Sericea Lespedeza Residues on Selected Tallgrass Prairie Grasses (Dudley & Fick., 2003)

Fact Sheet: Ecology and management of sericia lespedeza (Fuhlendorf et al., 2017)

Invasive Sericea Lespedeza

Adaptation, biology and control of sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), an invasive species (Farris, 2006)

Ecology and Management of Sericea Lespedeza

Pheasants Forever Youtube

EDDmapS

Mallory Shaw is a land conservation specialist with National Great Rivers Research and Education Center, currently residing in Woodford County with her 12-year-old son. She loves traveling, hiking as much as possible, bird watching and has a special affinity for wetlands.

Submit a question for the author

Question: Does the native you mention, Lespedeza virginica, have the same tannin levels and anthelmintic benefits as Auburn University’s cultivar of Sericea lespedeza, AU Grazer?

Question: Live in Oklahoma. Trying to get rid of sericea . It is taking over.

Question: I heard in southern USA , Sericia Lespedeza can be purchased by the 50# bag. And called “poor man’s alphalpa”

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Explore Our Family of Websites

Similar Reads

Need Landscaping Advice? Ask a Friend!

February 2, 2026 by Kathy Andrews Wright

An Accessible Alternative to Honeysuckle Management and Woodland Restoration

February 2, 2026 by Justin J. Shew, Addis Moore

Nine New Invasive Species Regulated in Illinois with Expansion of Exotic Weeds Act

February 2, 2026 by Emily Steele

Tiny Threatened Fish Species Re-introduced for the First Time

February 2, 2026 by Hugh Gabriel

Winter Weather Effects On Northern Bobwhite in Illinois

February 2, 2026 by John Cole

A Prairie Imagined

February 2, 2026 by Patty Gillespie

To Manage or Not to Manage: Primary nesting season and what it means

February 2, 2026 by Heather Herakovich

Responding to an Insidious Invader: Tackling a hydrilla outbreak

November 3, 2025 by Claire Snyder

Decreased Energy Use, More Savings…and More Wildlife

November 3, 2025 by Kathy Andrews Wright

Remembering John L. Roseberry

November 3, 2025 by John Cole