Photo by Michael R. Jeffords

Photo by Michael R. Jeffords

Each year between August and October, especially during hot and dry summers, landowners, deer hunters and wildlife enthusiasts are keeping an eye open for signs of an outbreak of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) in the local white-tailed deer herd.

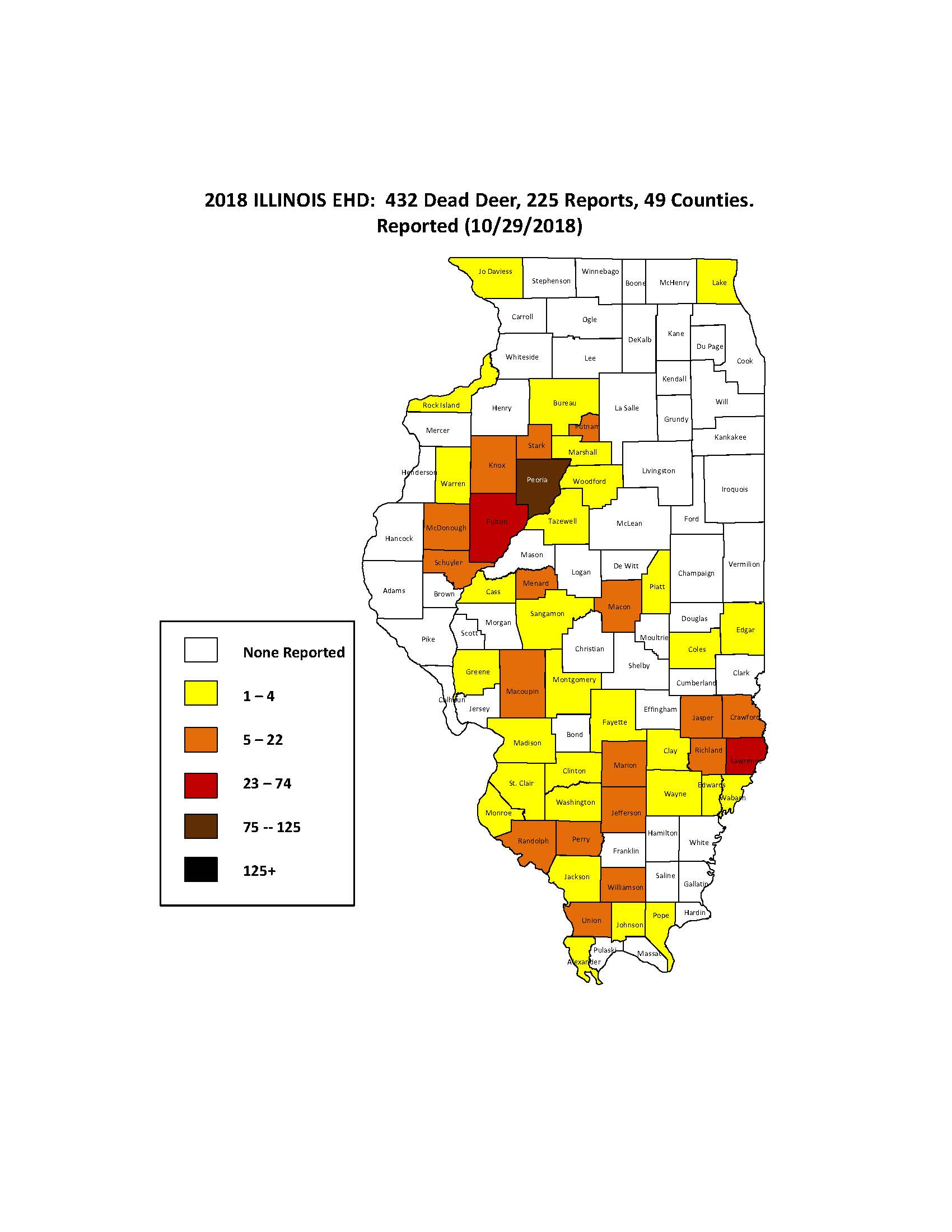

The Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) continually monitors the status of this disease with the assistance of the many individuals who report dead deer observed in the field. An increase in EHD activity from the previous four years was noted in 2018, although still significantly lower than the 2012 and 2013 seasons (see table). As for 2019, only three reports of five deer from three southeastern Illinois counties were received in July.

EHD is an acute, infectious and often fatal viral disease of some wild ruminants, including white-tailed deer. Characterized by extensive hemorrhages, this disease has been responsible for significant outbreaks in deer in the northern United States and southern Canada. Affected animals develop a fever, and typically many are found in, or adjacent to, water where they try to reduce their body temperature. Death can come quickly, from 8 to 36 hours after the onset of observable signs, to some infected deer. Other deer may die days or weeks later, and some will completely recover.

EHD is observed somewhere in Illinois every year, typically where receding water levels provide the muddy shoreline breeding habitat necessary for the EHD vector, a Culicoides biting gnat. EHD is transmitted when a gnat carrying the virus bites a deer. Outbreaks tend to be localized because environmental and habitat conditions play an important role in producing the right mix of virus, high gnat populations and susceptible deer. An insect-killing frost typically ends an EHD outbreak.

Signs of EHD appear about seven days after the deer has been bitten and include sluggishness, difficulty breathing, loss of appetite, salivation and swelling of the head, neck, tongue or eyelids.

EHD cannot be transmitted directly from deer to deer and is not considered to be hazardous to humans or pets.

The patchy annual distribution of EHD means that Illinois residents are key to tracking annual outbreaks. Illinois residents and hunters serve as IDNR’s eyes and ears in monitoring the annual distribution of this disease, as well as the health of the local deer herd.

To learn more about EHD, or report incidences of sick and dead deer, access the online Report Sick or Dead Deer reporting form at White-tailed Deer Illinois. You will be asked to report facts including the county, number and sex of dead deer and specific location of the deer.

According to Bob Massey, a District Wildlife Biologist with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR), as of the end of August IDNR had received 17 reports of EHD with 32 deer involved. That is lower than what might have been anticipated with all the flooding around the state. However, with the delayed or prolonged planting season that occurred, many reports of unusual dead deer will also be delayed. Many reports of dead deer, from whatever cause, coincide with farmers getting back into the fields with harvest activity. The delay in harvest will likely mean a delay in the discovery and reporting of carcasses. Even with reporting, verification of EHD at that point will not be possible due to the condition of the remains, but may have to be inferred from other factors. The reports we have gotten have not been concentrated in one area but scattered in the southern half of the state. A small flush of reports have come from the Wabash River drainage.

Doug Dufford retired from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Wildlife Resources, having serve as the Wildlife Disease and Invasive Species Program Manager. He continues to provide technical support on contract.

Submit a question for the author