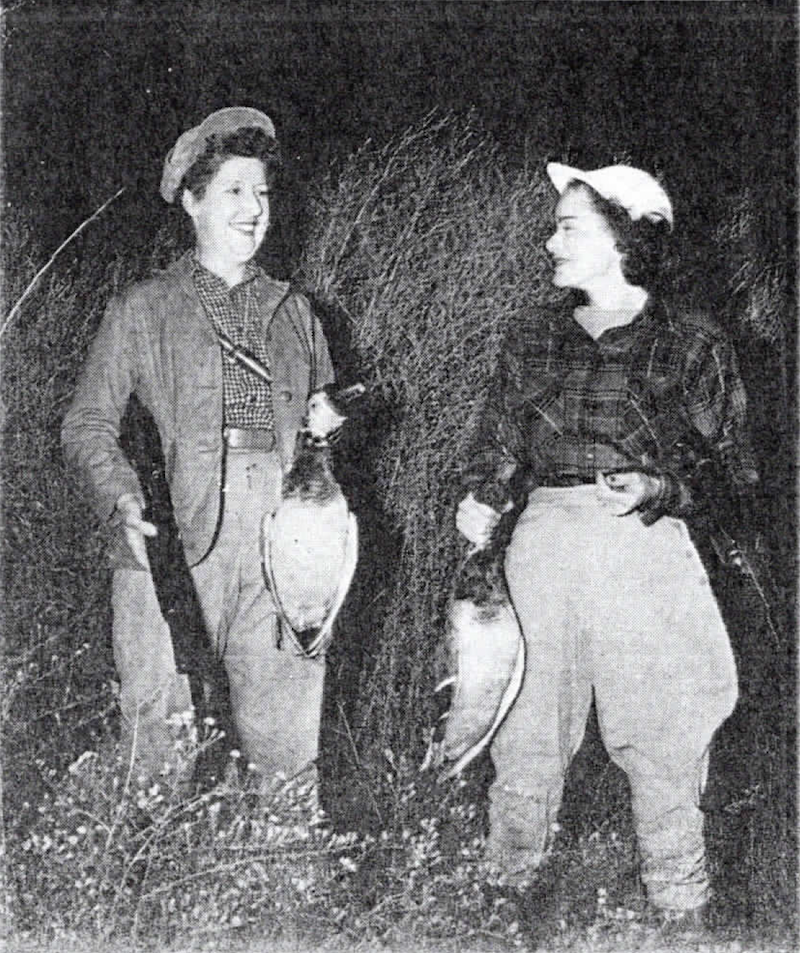

Photo courtesy of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

A Century of Hunting and Trapping in Illinois

A century ago, the Illinois Department of Conservation (IDOC) was formed. This story continues our centennial celebration series and focuses on some of the changes in hunting and trapping in the past 100 years. Learn what has changed and what has remained the same. You’ll also discover some interesting information along the way.

Protections for Game and Fish

The first real game law was passed in by the Illinois General Assembly in 1853, making it illegal to “kill any deer, fawn, prairie hen or chicken, quail, woodcock or wood partridge between the first day of January and the 20th day of July each year in the counties of Lake, McHenry, Boone, Winnebago, Ogle, DeKalb, Lee, Kane, DuPage, Cook, Will, Kendall, LaSalle, Grundy, Stephenson and Sangamon.” Two years later, the game law was rewritten making it illegal to sell game during the closed season, but that measure applied only to the northern 44 counties and Sangamon County. In 1873 a law expanded making the sale of game during the closed season illegal statewide. It also prohibited the killing any deer between January 1 and August 15.

The first officials tasked with the protection of game and fish were the three Illinois game wardens—one each appointed in Chicago, Peoria and Quincy—hired in 1885. In 1879 the Illinois General Assembly created the Illinois Fish Commission tasked with the duty of establishing fish hatcheries and implementing related fisheries programs. Also in 1879, a three-member state board of game commissioners was created, which in in 1903 became the Office of the State Game Commission and resulted in the creation of the first resident and non-resident hunting license requirements. Those two commissions were combined into the Game and Fish Commission in 1913.

In 1917, a Division of Fish and Game was created within the Illinois Department of Agriculture. The Division of Fish and Game was merged with the IDOC in 1928 and became the Division of Law Enforcement.

Legislation Also Developing at the Federal Level

The first federal law protecting wildlife, the Lacey Act, was adopted in 1900, making it illegal to transport live or dead wild animals, or their parts, across state borders without a federal permit. The federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act was implemented in 1918 to protect migratory birds. The Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act was passed in 1937 to help with wildlife conservation actions. Many additional acts would follow.

Our Conservation Legacy

“In 1925, the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and modern wildlife management were in their infancy,” noted Mike Wefer, Chief of the IDNR Division of Wildlife Resources. “However, as we look back these 100 years, it is interesting and affirming to see how much of our conservation mission and principles were already in place and how their tendrils still touch us today. Sure, some of the details have changed but as we view the Illinois Blue Book, 1925-1926, many of the core concepts are already there.”

The Illinois Blue Book, 1925-1926, contains a chapter on the Department of Conservation, authored by then Director William J. Stratton and Chief Assistant S. B. Roach. The opening statement reads:

“For several years sportsmen, commercial fishing interests, lovers of wild game, civic and conservation clubs and societies as well as citizens generally have urged the creation of a State department looking toward the conservation of all our natural resources as well as the protection and propagation of wild game and fish.”

Listed among the powers and duties of the new department were:

• To take all measures necessary for the conservation, preservation, distribution, introduction, propagation and restoration of fish, mussels, frogs, turtles, game, wild animals, wild fowls, and birds;

• To encourage and promote in every practicable manner, the interest of fishing and hunting in this State;

• To collect and publish statistics related to fish, mussels, frogs, turtles, game, wild animals, wild fowls and birds;

• To acquire and disseminate information concerning the propagation and conservation of fish, mussels, frogs, turtles, game, wild animals, wild fowls and birds, and the activities of this Department and the industries affected by conservation and propagation; and,

• To exercise all rights, powers and duties conferred by law and to take such measures as are necessary for the investigation of, and the prevention of pollution of an engendering of sanitary and wholesome conditions in rivers, lakes, streams and other waters in this State as will promote, protect and conserve fish, game and bird life and to work in conjunction with any other Department as shall be proceeding to prevent stream and water pollution.

IDNR’s mission statement today contains many of the same key points: To manage, conserve and protect Illinois’ natural, recreational and cultural resources, further the public’s understanding and appreciation of those resources, and promote the education, science and public safety of Illinois’ natural resources for present and future generations.

The 1925 Game and Fish Codes of Illinois

A palm-sized document, the Game and Fish Codes of Illinois 1925-1926, contains 63 pages detailing the wildlife codes for 1925-1926; the remaining 43 pages related to fishing codes. The regulations may seem archaic; some of the species that were considered game animals were different. Some of the names have changed. The black-breasted plover is now the black-bellied plover, the duck-hawk is the peregrine falcon and the pigeon hawk is the merlin. But as we see below, many of the core concepts are there. Wildlife and fish were being protected and managed through regulations, seasons and limits.

New Hunting Laws in 1925

In 1925, a new section to the Game Code made it necessary for hunting clubs to secure licenses to operate, and to keep daily registers of all migratory birds and waterfowl killed each day. Under the license, the premises and records were required to be open for inspection by duly authorized officers.

Prior to 1903, hunters could take an unlimited number of wood ducks. That year, a 50 wood duck bag limit was established, which was reduced to 35 in 1905 and 20 in 1907. Baiting of all ducks became illegal in 1908. The 1925 Game Code notes closure of the wood duck hunting season until Sept. 16, 1927.

The 1925 Game Code also noted the closure of the eider duck hunting season until Sept. 16, 1929. According to IDNR Waterfowl Program Biologist Doug McClain, the harvest of eiders, along with scoters, brant and other more ocean- and big water-affiliated waterfowl species, is legal today, although these sea birds are extremely rare within the Mississippi and Central Flyways and harvest is negligible.

Another new stipulation was that purchasers of fur or green hides were to secure a $10 license before engaging in their business. Today, a resident fur buyer license costs $50.50.

Species Not Hunted Today

Examination of the page on open seasons includes the November 10 to November 21 season on greater prairie-chickens, now an Illinois-endangered species. Hunting was permitted for black-breasted and golden plovers, as well as greater and lesser yellowlegs, from September 16 to December 31; all such species are now protected. A year-round season existed in 1925 for crows, blackbirds, blue jays, several species of hawks, great horned owls and cormorants. Not until 1936 was the Migratory Bird Treaty Act amended to protect insectivorous birds. Protection for eagles, hawks, owls and corvids was added in 1972. From that list of birds, only the crow may be legally hunted today.

MIA From the 1925 Game Code

Some species that are common today were conspicuous in their absence a hundred years ago.

In 1901 a “temporary” moratorium was established on white-tailed deer hunting that was to last for five years but actually lasted for 56 years. Not until 1957 was the ban on deer hunting lifted.

No mention of the wild turkey occurs in the 1925 Game Code as this now-popular forest game species had been extirpated from the state by 1910. Thanks to trap and transplant efforts, wild turkey hunting returned to Illinois in 1970.

Once commonly trapped throughout the United States, beaver numbers plummeted by the late 1800s because of overharvest. An effort to reintroduce beaver to Illinois began in 1929 and by 1951 Illinois opened its first legislated trapping season for beavers.

Guinea Pigs Make the 1925 Game Code

Review the 1925 code and you’ll find that the list of illegal hunting methods included the use of ferrets, weasels, guinea pigs and rats. Yes, you read that correctly! Taking these species along to enhance your hunt was prohibited.

Changes in Seasons and Limits

In a nutshell, in the past 100 years hunting and trapping seasons and limits have increased and decreased and remained static. Here’s a quick recap on some species.

While the season length remains relatively the same in length, with a slight shift earlier in the hunting season, the daily limit on rails has increased to 25 from 15 birds allowed in 1925.

Based on information collected from annual census routes and biological studies, the daily limits for bobwhite (from 12 to 8), brant (from 8 to 1) and snipe (15 to 8) decreased from 1925 to 2025.

When it comes to hunting cock pheasants, coots, geese and mourning doves, the season length and daily bag limits have remained relatively unchanged in 100 years.

The fur-taking season was initially created in 1908. The open dates for furbearer species have remained relatively unchanged in the past 100 years. Of most significance in the change in daily limits are rabbits (from 15 to 4), squirrels (from 10 to 5), badgers (currently one in the south zone and two in the north zone), river otters (currently five) and bobcats (one but only if you receive a permit).

Public Hunting and Fishing Grounds

Early conservation leaders John Muir, Gifford Pinchot and President Theodore Roosevelt were recognizing the need for public lands for conservation and to provide areas for public hunting and fishing. In the initial year of the Illinois Department of Conservation, the first tract of land to become Marshall State Fish and Wildlife Area was purchased. In 1927, the state began to purchase land around Horseshoe Lake in Alexander County to establish the first Illinois wildlife refuge.

Additional properties would be acquired in the first decades of the agency. The first eight recreational parks were acquired between 1934 and 1939 and included Fox Ridge State Park, Kankakee River State Park and Kickapoo State Park. Yet ahead of the agency was the 1932-1942 era of Civilian Conservation Corps construction projects at parks throughout the state. Recreational lakes would become a reality in the 1940s, primarily for fishing and boating but some were open to waterfowl hunting.

Currently, IDNR offers 428,730 acres of state owned, managed and leased lands for public hunting and trapping. How far things have come in a century.

Kathy Andrews Wright retired from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources where she was editor of OutdoorIllinois magazine. She is currently the editor of OutdoorIllinois Journal.

Submit a question for the author

Question: Using ferrets (along with sighthounds, usually, but sometimes with raptors as a partner) is actually really common in other parts of the world! My personal theory as to why it hasn’t really been much of a thing here is because we have easier access to firearm hunting (and so generally don’t use the dog as the actual method of harvesting the animal), and we tend to view the animals that ferrets are used to flush out of their holes (like rabbits) as game species, rather than a pest species. Definitely interesting to compare US vs. British/other former British colony hunting cultures and rules!

Were the guinea pigs and rats used as bait? I’ve never come across those in hunting before (although I know guinea pigs are a popular food in parts of South America)!

Question: My neighbor owns a piece od ground across the gravel road from me. As late as this past Memorial Day he was spraying poison to kill grass. this strip of grass is on the backside of his field. His ground sits higher then mine, and he has even busted drain tile in the road to get his property to drain better. There WAS a red fox that lived in the drain tile, gone now, I USED to have rabbits and squirrels in my front yard. Last time I had a squirrel was before his last spray. His property drains into mine anything I can do?

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Explore Our Family of Websites

Similar Reads

Available Soon, the 2026 Fishing Regulations Guide

February 2, 2026 by Kathy Andrews Wright

Nine New Invasive Species Regulated in Illinois with Expansion of Exotic Weeds Act

February 2, 2026 by Emily Steele

A Century of Conservation: How Illinois Brought Back the White-tailed Deer

November 3, 2025 by Kaleigh Gabriel

The 2025-2026 Upland Hunting Forecast

November 3, 2025 by Don Kahl

Gardner Camp’s Kid’s Trapping Camp Helps Ensure Trapping’s Future

November 3, 2025 by Tim Kelley

The Bowfin: Illinois’ Living Fossil

November 3, 2025 by Gretchen Steele

Illinois Waterfowl Hunting 2025-2026 Forecast

November 3, 2025 by Doug McClain

Return of the Giants: The reintroduction of alligator gar to the Cache River

November 3, 2025 by Mark Denzer, Rob Hilsabeck

The Sport Fish Restoration Act Has Been Supporting Fisheries Management for 75 Years: Part 2

November 3, 2025 by Vic Santucci

The Sport Fish Restoration Act Has Been Supporting Fisheries Management for 75 Years: Part 1

November 3, 2025 by Vic Santucci