American paddlefish captured for research in the Mississippi River pool 14 by the Mark N Morris (Whiteside County) Bridge in 2024. Photo by Shasta Kamara.

American paddlefish captured for research in the Mississippi River pool 14 by the Mark N Morris (Whiteside County) Bridge in 2024. Photo by Shasta Kamara.

One of the amazing things about fish is the diversity of species that exist. Fish are remarkable in that they can be found in virtually every aquatic environment on the planet, and have an impressive number of ways that they survive. As a few examples, some fish spit water to knock insects off plants so they can eat them, some fish can breathe air, and others can dry out and be perfectly fine when water returns. Fish also come in all kinds of colors, sizes and shapes.

The American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula), colloquially known as the spoonbill catfish, is one of the star species of the Mississippi River, and is a great example of a fish that has a unique shape. Paddlefish are an ancient lineage of fish that existed 65 million years ago. They do not have many bones, besides their jaw and ear bones, but rather, their skeleton is made of cartilage, which is similar to the material in our noses or ears.

While fish families such as bass or salmon contain many different species that are all closely related (e.g., largemouth bass, spotted bass, smallmouth bass and so on), there are only two species of paddlefish on the planet, with one native to the Mississippi and the other native to the Yangtze River in China. Sadly, the Chinese paddlefish was last seen in 2003, and was declared extinct around 2020.

While paddlefish have no close evolutionary relationship to catfish and are actually more closely related to sturgeons, their nickname is no surprise when you see these gentle giants up close. With a large spoon-shaped rostrum and nearly scaleless body, they are not easily confused with any other fish in the river. One of the unique features of paddlefish, and a common question that is often asked about them, is, “What is up with that big nose?”

Animals often rely on several of their senses to navigate the world, and many have special adaptations that allow them to not only survive but also thrive in their environments. From infrared sensing in snakes that help them seek out warm-blooded prey, or bees using the earth’s magnetic field to navigate through their surroundings and return to their hive, animals can take advantage of many different types of signals from their environments and prey. Such diverse adaptations aid animals in nearly all activities including foraging for food and water, navigation and communication.

The “big nose” on a paddlefish is known as a rostrum and is not a nose at all but rather an extension of its head that serves a number of functions that help the paddlefish survive in the muddy Mississippi. First, the cartilaginous rostrum of the paddlefish helps it maintain buoyancy within the water column as it forages. Paddlefish are primarily filter feeders as adults, eating small zooplankton in the water column. Like many fish, they have specialized parts within their large mouth known as gill rakers. For paddlefish, their gill rakers are long strands that act like a sieve to entrap their tiny zooplankton prey while allowing the water to pass through. As you can imagine, pushing a sieve through water can be tough; the large rostrum of the paddlefish helps cut through the water when they are filter feeding, and helps them maintain buoyancy while navigating their environment.

With rather small eyes and such a big snout, it comes into question how paddlefish find tiny zooplankton prey in the murky water. To help with this, paddlefish have special electroreceptors known as ampullae of Lorenzini scattered along their rostrum and head. When organisms, like potential prey, move through the water, they create weak electrical fields. The ampullae of Lorenzini allow paddlefish to detect these electrical fields, helping the fish locate their prey even, in low visibility conditions.

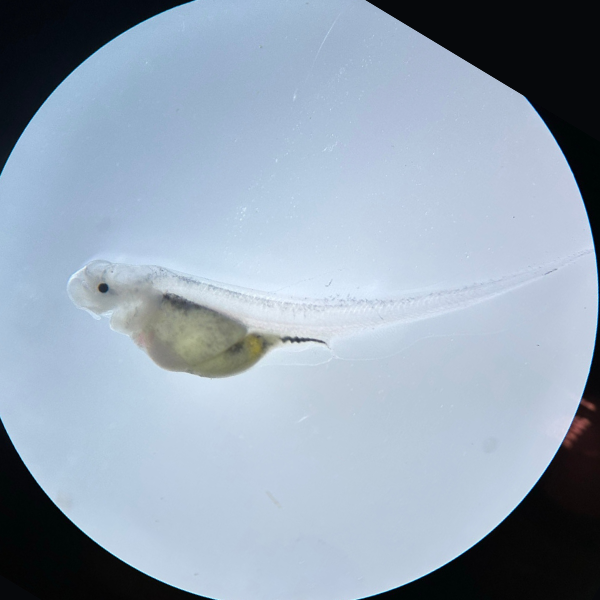

Interestingly, baby paddlefish start out looking relatively similar to many other species, and they do not have a large snout. But, as they develop, they begin to look more similar to closely related sturgeon. Gradually, their rostrum develops until it is nearly half of the body length of the young paddlefish. While larger paddlefish are filter feeders with poor sight and rely on electroreceptors to detect prey, larval paddlefish are primarily sight predators, seeking out their small zooplankton prey. This means that larval paddlefish are not in need of the electrical sensing capabilities that they are reliant on as juveniles and adults.

Unfortunately, paddlefish have been known to experience rostrum damage in the form of partial to full removal or breaking and healing of their rostrum from water forces around dams and boat strikes. With the loss of many of their electroreceptors and swimming advantage with maintaining buoyancy, there are concerns of how paddlefish fare after the loss of part, or in extreme cases, all, of their rostrum.

Paddlefish are also an important recreational and commercial species, sought out for their meat for consumption and eggs that contribute to the caviar industry. Because paddlefish rely on filter feeding, they do not bite a hook like other fish, but are instead snagged when they congregate around dams or other impasses during their spring spawning migration. With some overfishing occurring in the past, and limited migration and some loss of access to spawning habitat due to dams, managers are keen to preserve this species to ensure it can support these valuable recreational and commercial activities.

Paddlefish are an amazing species that support large recreational and commercial fisheries. With their striking appearance, tasty meat, and valuable caviar industry, they deserve our attention and preservation to ensure sustainable fisheries and keep people asking well into the future, “What is up with that big nose?”

Shasta Kamara is a PhD student in the Program in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her dissertation research focuses on paddlefish and investigating their interactions with anglers across different temperatures, and how their life history strategies and thermal tolerances differ across their large latitudinal range.

Cory Suski is a professor in the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois. For almost 20 years he has conducted research on many aspects of fishing.

Submit a question for the author