Photo courtesy of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Photo courtesy of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources.

Influenza (a.k.a. the flu) is a contagious illness caused by influenza viruses that have long been affecting humans and animals worldwide. Four types of influenza virus exist: A, B, C, and D (Lycett et al. 2019). They differ in their ability to infect hosts, cause pandemics, and in the severity of the disease they inflict. For example, Type A is commonly known as Avian influenza because it spreads naturally among wild birds but can also affect other mammals, such as dogs, cats, horses, pigs, and humans (CDC). Influenza Type B causes seasonal disease in humans that may result in severe respiratory illnesses (e.g., bronchitis and pneumonia) and exacerbations of chronic conditions such as asthma (Ashraf et al., 2024). Interestingly, although other mammals and birds can be infected with Type B, there is no zoonotic transmission (transmission from animals to humans; Ashraf et al., 2024). Type C also primarily affects humans, who are the natural reservoir, and causes mild illness. It is not seasonal and does not cause epidemics or pandemics like Types A and B. Finally, Type D, is predominantly associated with respiratory infections in cattle (Lee et al., 2025). In this article, we focus on avian influenza virus (AIV) in general and on the highly pathogenic avian influenza A (H5N1) in particular, summarizing preventive measures to help protect humans and pets from infection.

Avian influenza is caused by the Type A influenza virus, an RNA virus with surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). The presence of HA and NA on the virus’s surface provides a mechanism for subtyping (Bi et al., 2024). HA has 18 different subtypes (H1-H18), and NA has 11 different subtypes (N1-N11) (CDC). All subtypes affect birds, and depending on the combination of subtypes, different species of animals are affected (See Tables 1 and 2 on the CDC website for a list of other species affected based on Type A influenza virus HA and NA). However, H17N10 and H18N11 have been found only in Bats.

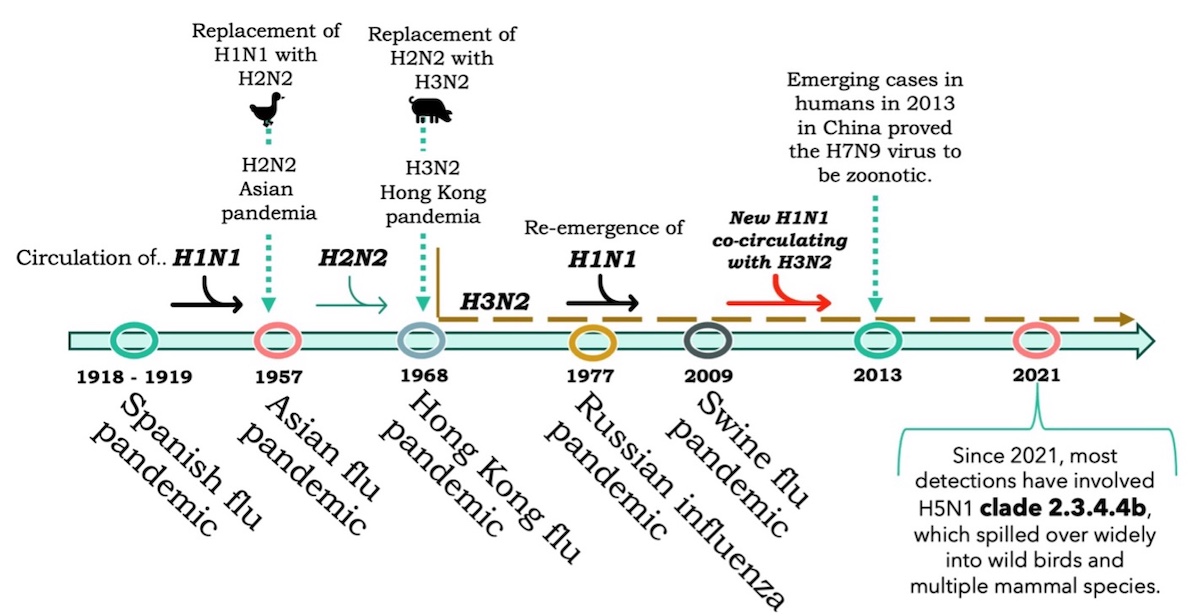

Although the avian influenza virus (AIV) is globally distributed, it has evolved into distinct subtypes based on geographic location, and in some cases, has affected humans and caused pandemics. The timeline (Figure 1) displays the names of influenza A virus subtypes that have circulated worldwide and their evolution, leading up to the latest human pandemic events. In some cases, AIV evolution occurs in wild or domestic birds or in other mammals, such as swine.

The AIV are also classified into two categories (CDC) based on how they affect birds:

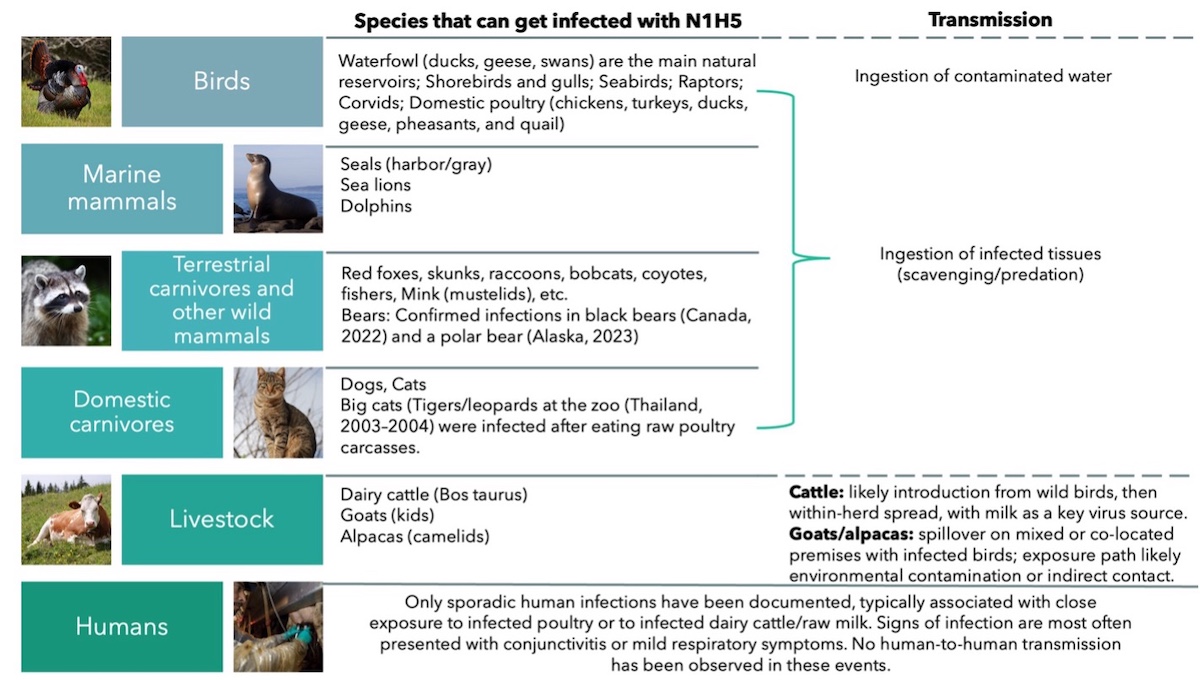

Birds are the natural reservoirs (and amplifiers) of avian influenza viruses. H5N1 have been detected in waterfowl (e.g., ducks, geese, swans), shorebirds and gulls, and many seabirds, raptors, corvids, and domestic poultry (chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese) (Alexakis et al 2024). However, H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b can infect mammals (e.g., carnivores, marine mammals, and some livestock) (see Figure 2).

Avian influenza-infected birds shed the virus via saliva, nasal secretions, and droppings, contaminating the environment, freshwater, or feed, equipment, and farm tools. Healthy birds acquire the infection when the AIV gains access to the virus’s entry points, such as the mucosa, skin, respiratory, or gastrointestinal tract.

Modes of transmission (how the virus finds the entry-points):

Ecological interactions affecting both direct and indirect modes of transmission include ingesting infected prey “predation” (i.e., raptors) or infected carcasses “scavenging” (i.e., crows). For other animals, such as dairy cattle, the virus is concentrated in milk. Calf exposure can occur during lactation (with spillover to other mammal species, such as domestic cats and raccoons, via raw milk). We note that fomites (inanimate objects or materials, such as clothes and tools, that, when contaminated, can carry the pathogen) may contribute to indirect transmission in farm settings, alongside direct contact, through milking systems and shared equipment (Caserta et al, 2024).

While avian influenza has been reported in poultry in North America over the last two decades, it wasn’t until December 2021 that the arrival of the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus subtype H5N1 caused mortality in domestic and wild birds. Since January 2022, the HPAI H5N1 virus (clade 2.3.4.4b) has caused the death of millions of domestic birds and thousands of wild birds in the USA, with spillover of bird flu to dairy cattle reported for the first time in March 2024 (Caserta et al. 2024) in Texas and rapidly spreading to 15 states as of November 2024. On December 14, 2025, the USDA reported the first known HPAI H5N1 in a dairy herd in Wisconsin (USDA), and Illinois reported H5N1 in poultry and wild birds. The Wildlife Medical Clinic at VETMED documented H5N1 in two Canada geese from Urbana-Champaign, a red-shouldered hawk from Effingham, and a great horned owl from Tuscola. As of December 2025, no dairy cattle or human H5N1 cases have been detected in Illinois. However, 25 wild bird die-offs were reported between late August and December in 14 counties, as well as 1 commercial poultry farm detection in St. Clair County and 5 backyard poultry detections in Jefferson, Jersey, Knox, Madison, and Vermillion counties (IDPH).

In summary, prevention is the key. Protect yourself by avoiding contact with sick/dead birds or animals and protect your pets by keeping them on a leash and under supervision when outdoors. If a pet shows fever, nasal discharge, breathing problems, red/irritated eyes, or neurologic signs (tremors, incoordination), call your veterinarian. When you identify sick animals at a farm, isolate promptly, contact your veterinarian/state animal health official, and strengthen on-farm biosecurity (controlled entry, dedicated tools, clean/dirty lines).

Bird flu prefers waterfowl; therefore, do not promote bird congregation by feeding them. However, providing feed and housing for wild birds may not create the same risk as for waterfowl. The USDA does not recommend removing sources of food, water, and shelter for wild songbirds (unless you also take care of poultry). Keep bird feeders clean and disinfect them every 10 to 15 days, and clean and provide fresh water in bird baths at least every 2 days. Protect your backyard poultry and pet/companion birds by separating them from wild birds.

Dr. Nelda Rivera's research focuses on the ecology and evolution of new and re-emerging infectious diseases and the epidemiology of infectious diseases, disease surveillance, and reservoir hosts’ determination. She is a member of the Wildlife Veterinary Epidemiology Laboratory and the Novakofski & Mateus Chronic Wasting Disease Collaborative Labs. She earned her M.S. at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and D.V.M at the University of Panamá, Republic of Panamá.

Dr. Nohra Mateus-Pinilla is a veterinary Epidemiologist working in wildlife diseases, conservation, and zoonoses. She studies Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) transmission and control strategies to protect the free-ranging deer herd’s health. Dr. Mateus works at the Illinois Natural History Survey- University of Illinois. She earned her M.S. and Ph.D. from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Submit a question for the author