White-tailed deer have been the most frequently observed mammal species in the multi-year camera trap study conducted by the Illinois Natural History Survey. Photo courtesy of Max Allen and Nathan Proudman.

White-tailed deer have been the most frequently observed mammal species in the multi-year camera trap study conducted by the Illinois Natural History Survey. Photo courtesy of Max Allen and Nathan Proudman.

Statewide mammal study documents species with photo bursts.

Nathan Proudman and U of I undergraduate students have seen a female bobcat and her yearling trying to cross rough waters after a severe flooding in southern Illinois. They’ve also observed a female opossum carrying four young on her back. These images came from cameras placed in strategic spots across Illinois to study mammals.

“This is an attempt to monitor mammal populations throughout the state,” said Proudman, a postdoctoral research associate at the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS). The study, funded by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR), began its fifth year in fall of 2025.

“Camera trap data is so versatile,” Proudman said. “You can use it to determine ecology and behavior. We may see, for example, an armadillo entering a new ecosystem for the first time. All of this is valuable for making conservation plans.”

To do the surveys, Proudman follows the Critical Trends Assessment Program (CTAP). In the program run since 1997, scientists have collected plant, bird and arthropod data at more than 600 randomly selected sites statewide on public and private lands. CTAP is designed to help scientists understand past and current conditions of Illinois’ ecosystems. They survey grasslands, wetlands and forests, with landowners giving permission for scientists to study the sites.

The camera study has documented mammalian activity on up to 30 grassland and 30 forests annually, and in fall and winter of 2025, the researchers are studying 30 urban, 30 wetland, 30 grassland and 30 forest sites throughout the state.

The mammal monitoring begins in October and ends in May. Cameras are strategically placed to document mammalian presence and behavior. The best time to monitor mammals is in fall and winter when there’s less vegetative cover, which makes it easier to capture the activity on camera.

“Furbearers are usually more active during the winter too, as most have their reproductive periods then and are patrolling home ranges and seeking mates,” Proudman said.

The camera survey uses motion and heat detection to register a mammal species walking in front of the camera and will trigger a three-photo burst.

“We leave cameras out running passively and don’t return to the site until we collect the cameras,” Proudman said.

IDNR specifically monitors the distribution and abundance of furbearer species such as coyotes, skunks, bobcats and foxes, using roadkill counts and spotlight surveys.

“By adding camera traps we can have a continuous passive collection of data over a long time,” Proudman said. “We’re finding camera trapping is very effective in finding out where these animals are and how often they pass in front of the camera.” Though the team focuses on IDNR-conservation priority furbearing mammals, the researchers capture a broad range of species, from tiny weasels up to white-tailed deer.

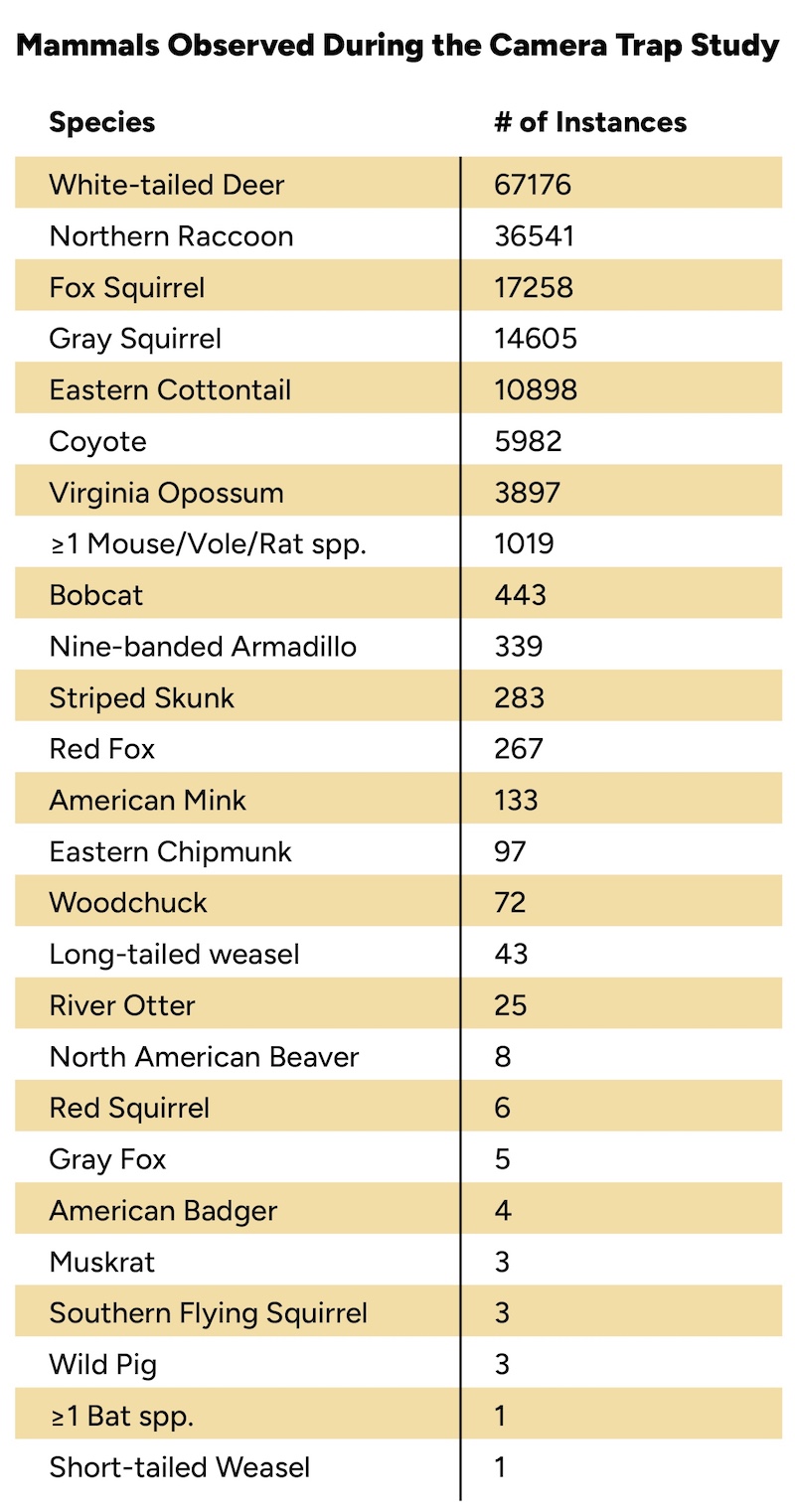

“We have captured 26 mammal species on camera so far,” Proudman said.

The cameras typically capture photos of animals that use game trails.

“White-tailed deer pioneers start the paths of least resistance, and those game trails are then used by other mammals, such as coyotes, foxes, bobcats and skunks,” Proudman explained. “We will also document tree squirrels running across the paths.”

“We have more than 500,00 photos from the first four years,” Proudman said. A team of undergraduate students spend two to three months looking through the images and tagging all the photos.

Proudman said the photos show fascinating behavior of mammals. For example, “We’ve seen a few bucks jostling right in front of the camera, sparring and pushing each other,” Proudman said. “We saw a coyote staring at a deer. In my interpretation, the coyote was thinking, should I and then probably not.”

Proudman said since the camera project began the study has been tracking bobcat occupancy and distribution increasing across the state.

“Historically, bobcats were almost wiped out from unregulated harvest, changes in land use and deforestation,” he said. In 1971, bobcats were added to the Wildlife Code which stopped the unregulated harvest of bobcats. They were then added to the state threatened species list in 1977. By 1998, bobcats had been reported from 99 of Illinois 102 counties and they were taken off the threatened species list in 1999. Increases in populations have been documented by this and other research over the last several decades.

Bobcats have been seen on cameras in this study all the way north to East Moline.

We have seen some bobcat on our cameras in the forested riparian areas near Danville,” he added, but fewer in the heavily agricultural zone of central Illinois.

Proudman said one concern brought to light since the camera surveys started is the decline in gray foxes.

“We got gray foxes in our first year, 2021, on our cameras, but we haven’t gotten them since,” he said. Data from Southern Illinois University studies have also documented the decline, he said. “The decline could be related to disease, habit unsuitability, human impact and, potentially, coyote predation.”

These data support the IDNR’s decision to close the hunting and trapping season for gray fox effective immediately in July 2025.

“Even though Illinois hunters and trappers harvest very few gray foxes, this closure will remove any additional pressure and additive mortality from harvest,” according to illinois.gov. “The Illinois Department of Natural Resources will continue to conduct annual surveys and evaluate the gray fox population in Illinois.”

Armadillos began to show up more frequently in Illinois during the 1990s and ever since then, they have been working their way farther north in the state. Exactly how they got into southern Illinois is not clear, but it believed to be a combination of natural range expansion (they walked) and some that were intentionally moved and introduced by individuals (not by IDNR). Regardless, they are here and have been moving north.

Among the most abundant mammals captured on the cameras are raccoons and white-tailed deer.

The camera surveys point to how humans have altered landscapes and changed mammalian populations.

“Ecosystems have changed over time and the scales have been tipped for those species that are adaptable, have generalist diets and can live in a variety of habitats,” Proudman said. “Those species are increasing and the specialist species that require very specific habitat types are often the ones struggling.”

Sheryl DeVore writes environment and nature pieces for regional and national publications and has had several books published, including “Birds of Illinois” co-authored with her husband, Steven D. Bailey.

Submit a question for the author