Photo courtesy of Frank Sladek.

Photo courtesy of Frank Sladek.

With the “dog days” of summer upon us, most Illinois fish species seek shelter in deep waters offshore where they can cool off, conserve energy and wait for conditions to improve. When the sportfish leave their shallow water haunts in the heat of summer, another, more peculiar, fish makes their presence known. A fish that is not bothered by low oxygen levels, warm water or weed-choked habitats. One that has been around since the Triassic period, when dinosaurs began their rise to power on planet Earth. A living fossil that has survived for millions of years with the help of some seriously amazing adaptations.

Gar refers to several species of bony, warm water fish that inhabit shallow, vegetated areas in waterways across the United States and Central America. Illinois is home to four species, including the smallest and largest species in the gar family (Lepisosteidae). These include the longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus), shortnose gar ( Lepisosteus platostomus), spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus) and the massive alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula). Adults range in size from 2 feet to more than 10 feet long and, depending on the species, gar are capable of growing to massive sizes in many parts of their range. If you’ve ever come across one of these odd animals, it quickly becomes apparent that they are no ordinary fish.

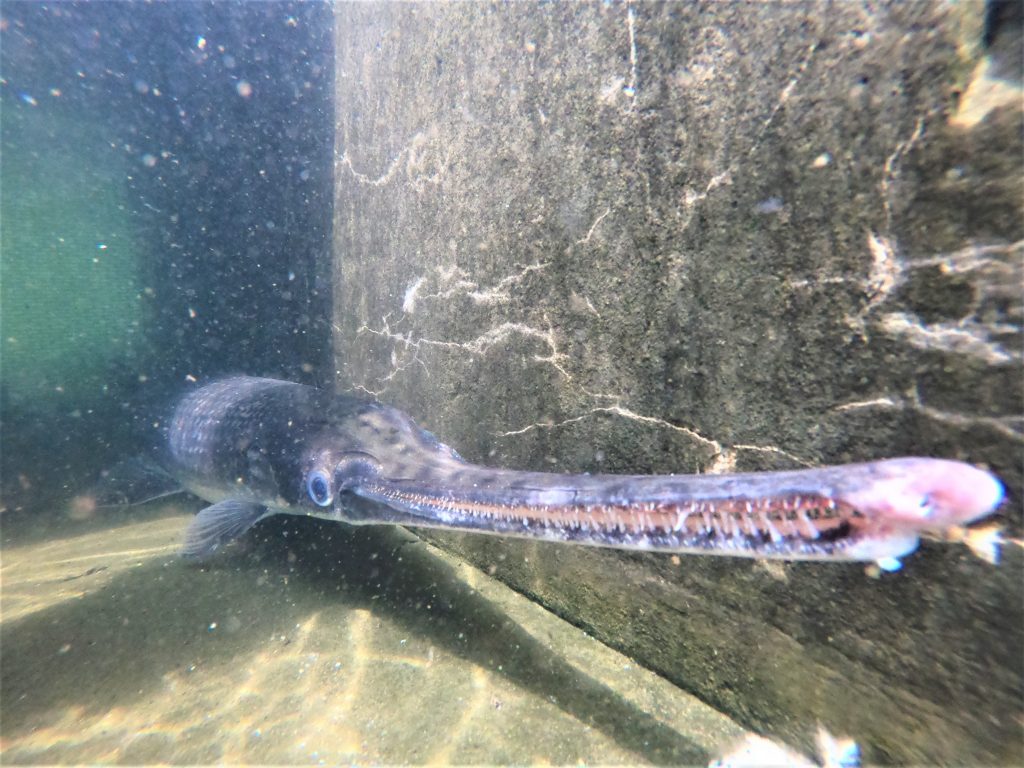

With their long, torpedo-shaped bodies and lazy swimming habits, gar often get mistaken for logs. In the summer months, small groups of gar can be seen just under the water’s surface, basking in the sun like a cat on a windowsill. The only indicators an angler may get that the “log” they are seeing is a fish, is an occasional fin twitch or glimpse of a long, toothy snout breaking the surface. Speaking of snouts, the jaws of a gar can be twice the length (or more) of their head, adding some serious size to these already lengthy fish. The gars’ bony jaws are filled with more than 80 needle-like teeth, giving them a ferocious appearance. But their numerous teeth and sausage shaped bodies are only part of what makes them so unique.

Gar possess a series of amazing adaptations that have allowed them to thrive in aquatic habitats for more than 200 million years. Even as mass extinction events wiped out the dinosaurs. Much of this has to do with their anatomy, with internal and external adaptations helping them avoid extinction in an increasingly hostile world.

Like most fish, gar are covered in scales. A closer look at their scales reveals several unique features. Gar are covered in a primitive scale known as “ganoid scales.” While most fish scales are made of materials such as calcium and collagen (found in bones and skin), ganoid scales are covered in a rock-hard material called “ganoine,” similar to tooth enamel. This substance makes the scales extremely tough and glossy, like teeth. Ganoid scales also have a joint built into their base, allowing the scales to lock together like medieval chainmail. These tough scales give gar a flexible, nearly impenetrable suit of armor. Other ancient fish, including paddlefish, bowfin and sturgeon, also have ganoid scales.

Another adaptation of gar is found in their eggs. While gar meat can be quite delicious, gar eggs are highly poisonous to other animals, including humans. When ingested, the eggs can cause vomiting and severe stomach pain. In other words, don’t make a jar of gar caviar! In wild populations, many fish never make it out of the egg due to environmental factors, including predation from other animals. For unborn gar, this is not a problem due to the toxic casing that surrounds them.

As soon as gar are out of their protective eggs, a helpful, yet morbid, behavior occurs. Early in life, gar are cannibals. When any fish emerges from their egg, they are a moving target for all kinds of predators. The gar’s solution? Grow big and grow fast. How fast can they grow? Recently, a 10-week-old alligator gar was pulled from an outdoor pond at the Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ (IDNR) Jake Wolf Memorial Fish Hatchery. The fish measured 15 inches long and weighed nearly 2 pounds! In the wild, it is not uncommon for certain species of gar to reach lengths of 12 inches in under 3 months. Compare that to cold-water fish, such as salmon, which can take more than a year to reach that size.

The gar’s most fascinating adaptation is not their armored scales, toxic eggs or a cannibalistic childhood. It is their ability to breathe air. In the summer months, low oxygen levels and poor water quality drive most fish to deep water. Not gar. Most fish have an internal organ known as a swim (gas) bladder. This long, balloon-like organ lets fish control their buoyancy, allowing them to rise or fall in the water column without wasting energy. Much like when humans are in a pool. If air is in our lungs, we float. If we let the air out, we sink.

Gar swim bladders go a step further. Their swim bladder is covered in blood vessels and tissues, making it resemble a primitive lung. Instead of only using their gills to breathe, gar can also use their swim bladders to store oxygen from the air. This process is known as “obligate air breathing” and is done when there is not enough oxygen available in the water. On hot summer days on large rivers and lakes, anglers often observe what they believe to be carp or catfish, sitting just below the surface of the water. Those fish are often gar coming up to “gulp” air.

Using this method of breathing, gar can remain in poor water quality after most fish have left the area. By remaining in these areas, gar also have a smorgasbord of prey to feast upon, with little competition from other fish. This air breathing behavior also lets gar survive in areas after floods, when water bodies like oxbows and sloughs become disconnected from rivers as high water recedes. Amazingly, out of the 30,000+ species of fish on earth, less than 2 percent are known air breathers, making this behavior extremely rare in modern fish.

With their sharp teeth, menacing appearance, appetite for fish and air breathing abilities that evoke images of low budget horror films, these prehistoric predators have a poor reputation amongst anglers and the public. Often seen as a “trash fish,” gar are frequently left on the banks of rivers to perish, a slow death for an air-breathing fish. As navigation increased in large rivers of the U.S., and backwaters drained, gar have been challenged to find all the space needed for success. Adult alligator gar, in particular, have likely been competing with shipping in the main channels during summer low flows, and have found fewer of the marsh habitats for reproduction in the middle and lower Mississippi River haunts. Capable of reaching lengths of over 10 feet and weights of 300 pounds, many of these huge fish were targeted and killed due to misinformation and fear. In Illinois, alligator gar were declared extirpated (locally extinct) in 1994. Increased interest in angling these giants has spurred on restoration efforts like those occurring in Illinois.

Fortunately, the Illinois fish hatchery system is working to return gar to Illinois waters. Three of the four species (longnose, shortnose and spotted gar) are common in Illinois, but alligator gar are relatively rare. To continue support and reintroduction of these megalithic creatures, Jake Wolf Memorial Fish Hatchery and Little Grassy Fish Hatchery received more than 60,000 alligator gar in 2023 from Private John Allen National Fish Hatchery in Tupelo, Mississippi.

As in past years, alligator gar arrived at the hatcheries at just 2 days old and at the size of a pinkie nail. Resembling striped tadpoles, these fast-growing fish are now approaching lengths of 10 inches at the age of 2 ½ months. For the first time in 5 years, alligator gar will be released into state waters, to the benefit of aquatic ecosystems and sport anglers alike. It is predicted that within 10 years the gar released in 2023 will reach lengths of 6 feet and weights of more than 100 pounds. For more information on the alligator gar recovery program in Illinois, visit this link.

Ecologically, gar are valuable members of a complex food web of more than 100 species present in the larger rivers of Illinois. The relationships between species have evolved to keep a balance in these systems. Insect larvae, including mosquitoes, are one of the dietary items of gar early in life. Those same balances also provide protection from invasive species. The most complete native communities have the most resilience. While gar will feed on some of these invasives, including bighead and silver carp of all sizes, they cannot control (or eliminate) invasive species alone.

In terms of aggression, gar are normally mild mannered. While their needlelike teeth are extremely sharp and their scales resemble arrowheads, gar are quite a passive fish. When encountered in the wild, gar will often float near the surface, remaining almost entirely still; swimming away only when disturbed (ex. when bumped by a canoe or kayak). When hunting prey, gar can deliver a slashing strike, capturing fish and other animals in their bony jaws. Human bites are rare and usually occur if anglers get too close to a gar’s mouth after it is landed. If angling for these fish, long pliers are recommended.

With their amazing adaptations and odd appearance, gar are a wonder of the fish world. Angling for these unique fish may require sturdy tackle and special tactics depending on the target species. Size your gear appropriately. Catfish tackle, such as bobbers and bottom rigs, baited with chunks of cut fish are popular choices. Bass lures like spinnerbaits and topwater lures fitted with frayed nylon rope or yarn also catch gar, as the strands get caught in their many teeth. If you suspect a gar is biting, waiting to set the hook is also encouraged, as most hooks cannot penetrate their boney jaws. Circle hooks help prevent gar from swallowing hooks.

As with any fish, if you are not planning on eating a gar, catch and release is encouraged. This practice extends to alligator gar, due to recovering populations and their potential as a trophy fish. For those who want to keep an alligator gar, an Illinois harvest rule went into effect in 2019. The regulation allows the sport harvest of one alligator gar per 24-hour period, with no commercial harvest allowed. Anglers are encouraged to report any alligator gar harvest or catches with a picture to IDNR. An information page is included in the annual regulation book, with a phone number to report your catch. Requested information will help biologists gather data regarding fishing pressure and harvest.

IDNR continues to work with researchers and biologists to better understand the ecological importance and benefits of gar. Considering this family of fish has been battling the odds for eons, one can hope that these living dinosaurs will start being recognized as the fascinating fossil fish they have always been.

Public tours of the hatcheries are available by appointment by calling (309) 968-7538. Follow the hatchery on Facebook.

Frank Sladek is the Urban and Community Fishing Program Coordinator for Northern Illinois. His program offers free fishing clinics, aquatic resource education classes, school programs and IDNR displays at nature and children’s events for residents north of I-80, outside of Chicago.

Submit a question for the author

Question: Well written and very informative article Frank! Will the Alligators be present in the Sangamon River and Salt Creek?