Photo by Mark Gibboney.

Photo by Mark Gibboney.

The annual cycle of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) transmission in Illinois is dependent on weather and water conditions. During periods of drought when water levels go down in lakes and rivers, the exposed, muddy shorelines can become a breeding ground for insects of the genus Culicoides—commonly referred to as midges, gnats, or “no-seeums.” While the pin-prick-like bites from these small insects are an annoyance, they do not transmit EHD to people. EHD is not considered to be hazardous to people or pets.

The story is different in the case of white-tailed deer. The virus that causes EHD is not transmitted directly from deer to deer but rather through the bite of a virus-infected midge. This infectious, viral, vector-borne disease is often fatal to deer.

Periods of drought exacerbate the spread of the disease because deer are forced to congregate at remaining water bodies, the banks of which serve as midge habitat. The longer the deer are exposed to the midges, the higher their chance of being infected by the virus.

It isn’t until about a week after a deer has been bitten that it may begin to show signs of illness. These include swelling of the head, neck, eyelids or the tongue—which sometimes hangs out of the deer’s mouth. Infected deer often appear sluggish, have breathing difficulty, lose their appetite, exhibit excessive salivation and may lose their fear of people.

As the disease progresses it causes fever and extensive internal hemorrhages. Which is why infected deer often seek out water bodies to try to reduce their body temperature and to slack their intense thirst. Some deer are able to recover, but for others death comes quickly—sometimes within a day after showing observable signs of infection.

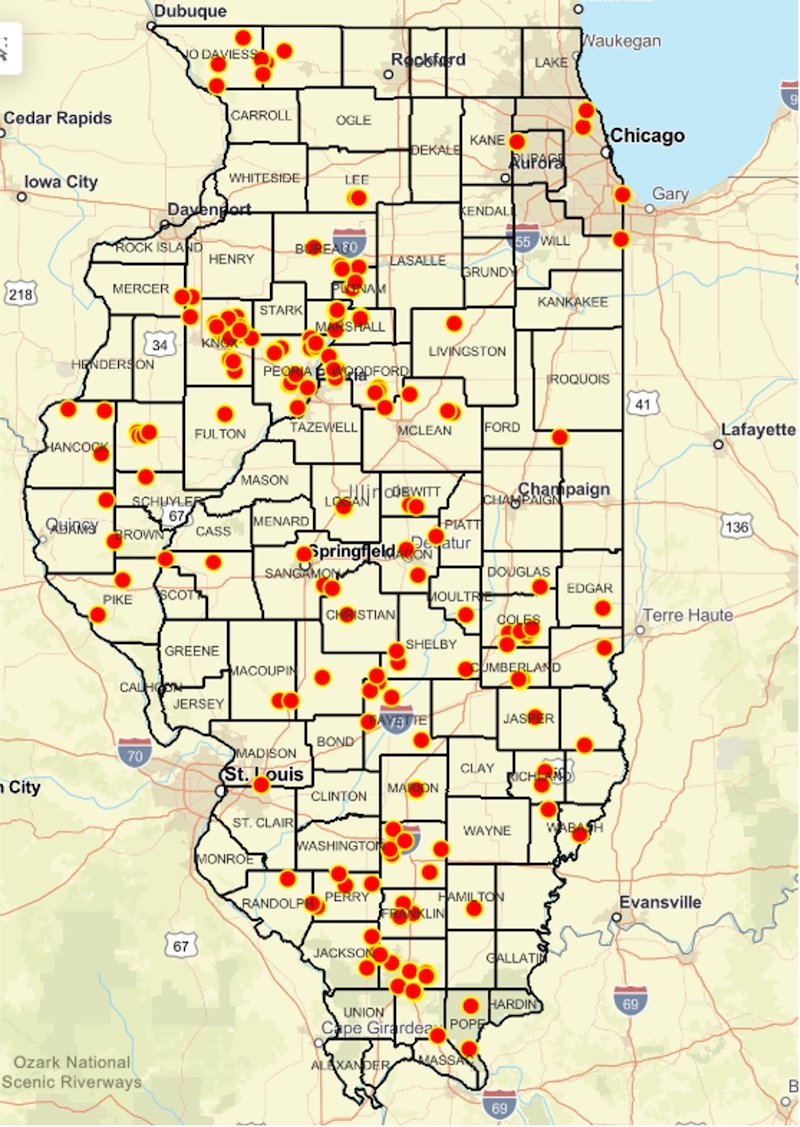

Because transmission is impacted by local weather and habitat conditions, the disease is not evenly spread across the state each year but rather shows up in hotspots of localized deer die-offs. In the article Occurrence of Hemorrhagic Disease in Illinois: Four Decades of Spatial and Temporal Changes the authors explain that “changes in precipitation, wind velocity, and temperature can affect the distribution and abundance of the arthropod vector and the development of the virus in the hosts.”

While sick or dead EHD-infected deer are often found in or near waterbodies, which can make them easier to find and report, gender identification and collection of tissue samples is not always possible. This is because deer with EHD usually bloat after they die and tend to decompose quickly, hampering data collection.

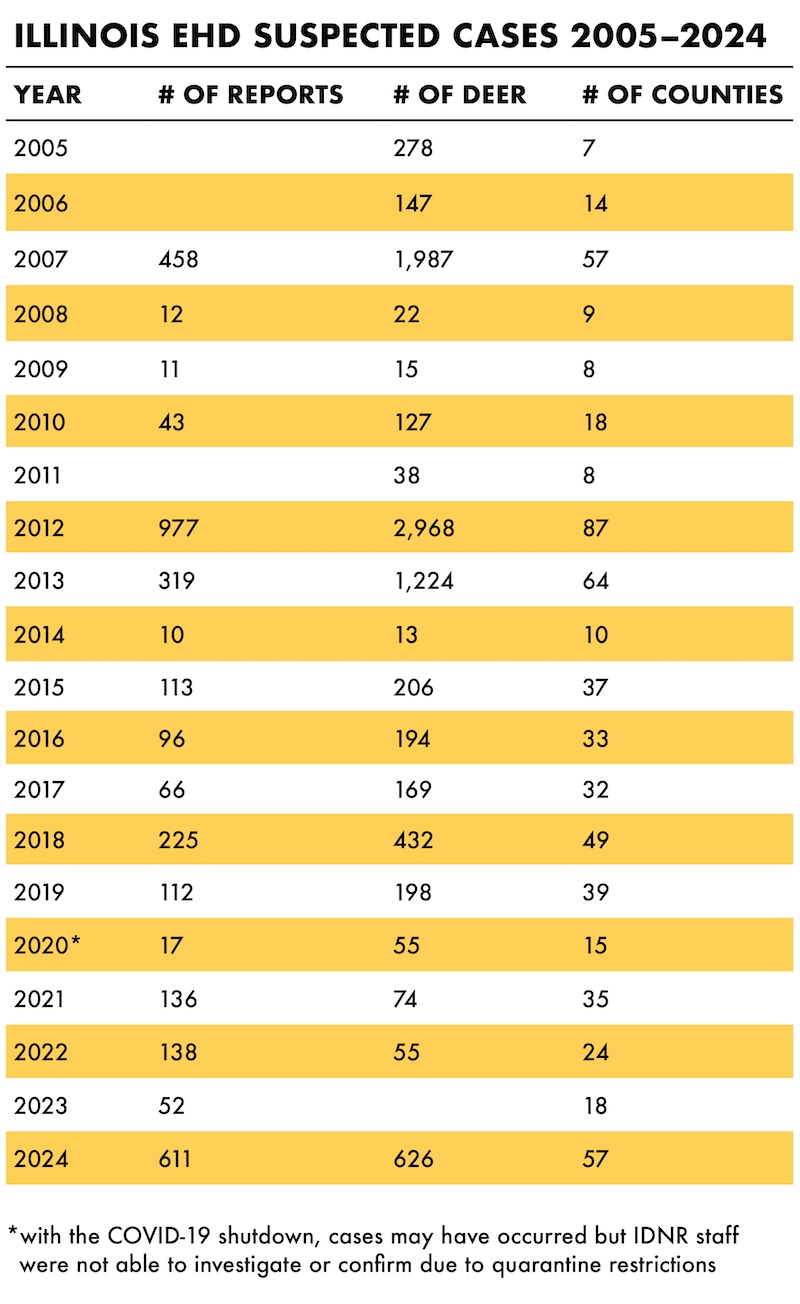

The Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) collects statewide data on the extent of EHD outbreaks each year. Because the abundance of the midges peak from August to October, particularly during hot and dry summers, hikers, deer hunters and landowners are encouraged to watch for and report suspected cases of EHD to the IDNR. A hard frost typically kills the midges and ends the annual EHD outbreak.

In 2024, there was an increase in both the number of suspected EHD-infected deer and number of counties with observed cases. A total of 626 dead EHD-suspected deer were reported, the highest number in a decade and fourth behind the numbers of deer reported in 2007, 2012 and 2013. More data is available in this table of annual EHD reports collected by the IDNR.

Last year there were EHD reports from more than half the counties in Illinois (57 out of 102). The highest number of reported deer came from Knox, Peoria, Perry, Jasper and Jackson.

While the distribution of EHD may have been relatively high compared to most previous years of monitoring, with the documentation of about 600 suspected cases, the associated impact of mortality on deer herd dynamics across the state, and even at the county level, was minimal.

To report incidences of sick and dead deer, access the online Report Sick or Dead Deer reporting form. You will be asked to report the county, the number, age, and sex of dead deer, the deer’s proximity to water and the specific location of the sighting. Photos are encouraged.

To learn more about EHD go the white-tailed deer page on the Wildlife Illinois website or read previous updates in past issues in OutdoorIllinois Journal by searching for EHD in the OutdoorIllinois Journal Library.

Laura Kammin jest specjalistką ds. zasobów naturalnych w National Great Rivers Research and Education Center. Wcześniej pracowała w Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant, University of Illinois Extension, Prairie Rivers Network oraz Illinois Natural History Survey. Tytuł magistra ekologii dzikiej fauny uzyskała na University of Illinois w Urbana-Champaign.

Prześlij pytanie do autora