Photo by David Ellis, USFWS.

Photo by David Ellis, USFWS.

Ticks can carry pathogens—such as bacteria, viruses and protozoa—that may be transmitted to wildlife, humans and their companion animals. However, not all ticks carry and transmit these pathogens, and not all animal hosts are susceptible to the same pathogens or develop the same diseases (signs and symptoms). Here, we list medically important ticks found in Illinois, along with the diseases they may transmit to humans, canines and felines.

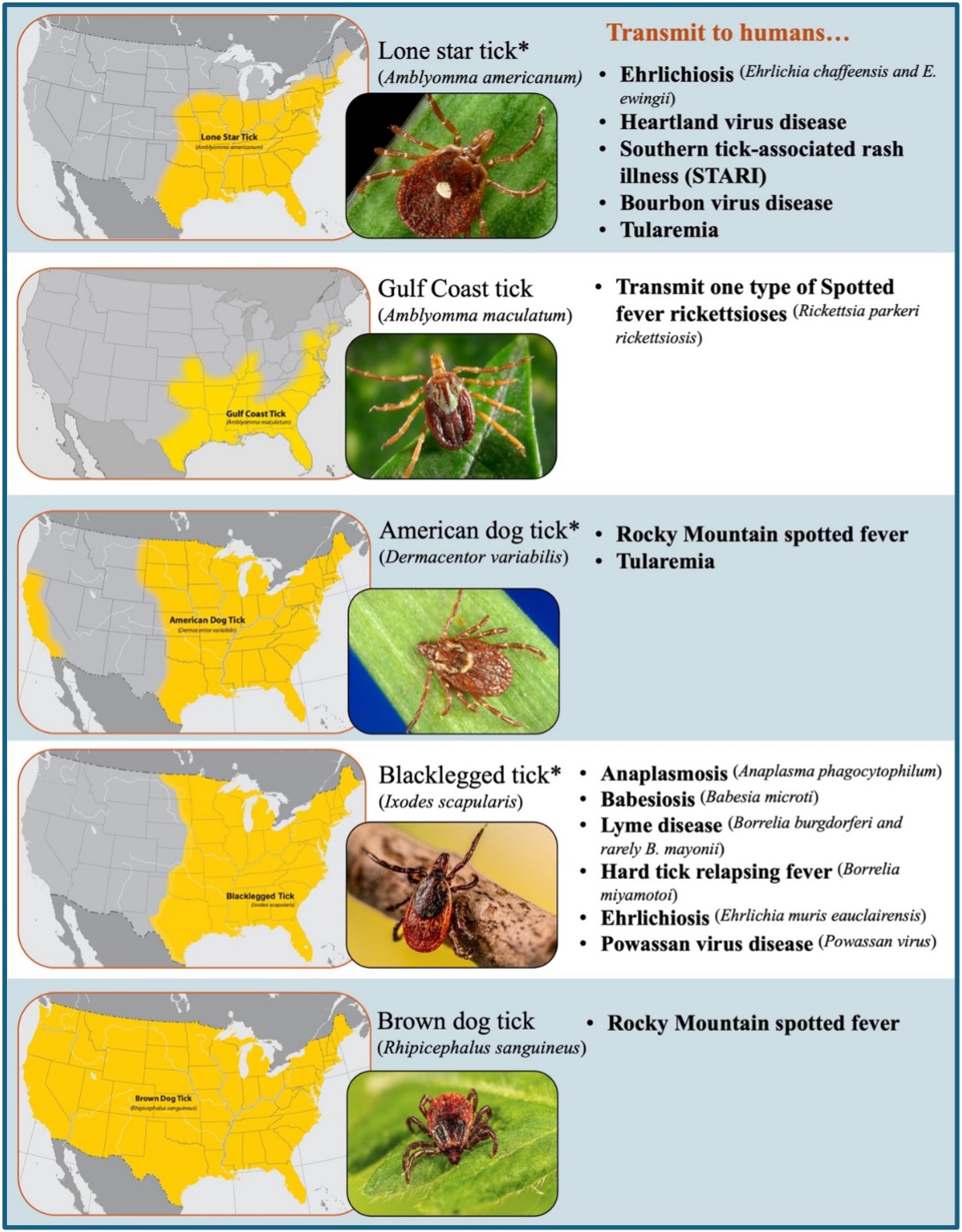

Different tick species are found worldwide; however, only a select few bite and transmit pathogens that cause diseases in people. Eight tick species in the U.S. can transmit pathogens to humans, of which five are found in Illinois (Figure 1) (CDC). Of these five tick species, three are considered the main vectors of tick-borne diseases in Illinois: Lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum), American dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis) and blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis).

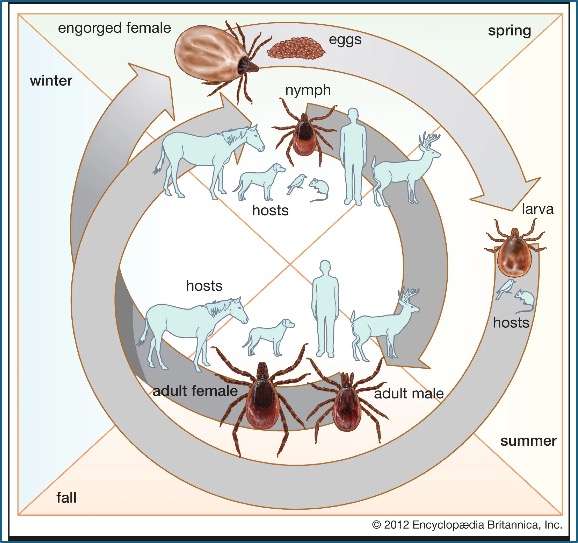

Most tick-borne diseases that affect humans can also affect wildlife, as well as dogs, cats and other domestic animals. However, which animal species will be affected will depend on the specific pathogen the tick vector is carrying. For example, let us look at the cycle of one of the most famous tick-borne diseases, Lyme disease (Figure 2). Through the bite of an infected blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis), the bacteria that cause Lyme disease (B. burgdorferi) can be transmitted to humans and other animals.1 While reports of Lyme disease in humans and dogs are more frequent, cats can also contract the disease. However, cats rarely show signs of infection with B. burgdoferi. If cats develop clinical Lyme borreliosis, they may show signs such as lameness, fever, anorexia or fatigue; although most cats may appear healthy.2 Unfortunately for dogs, if treatment is delayed, Lyme disease can lead to extensive joint damage, kidney failure, cardiac complications and neurologic dysfunction.3 Common signs of Lyme disease in dogs include fever, lethargy and loss of appetite. Seizures and facial paralysis have been reported due to nervous system damage.3

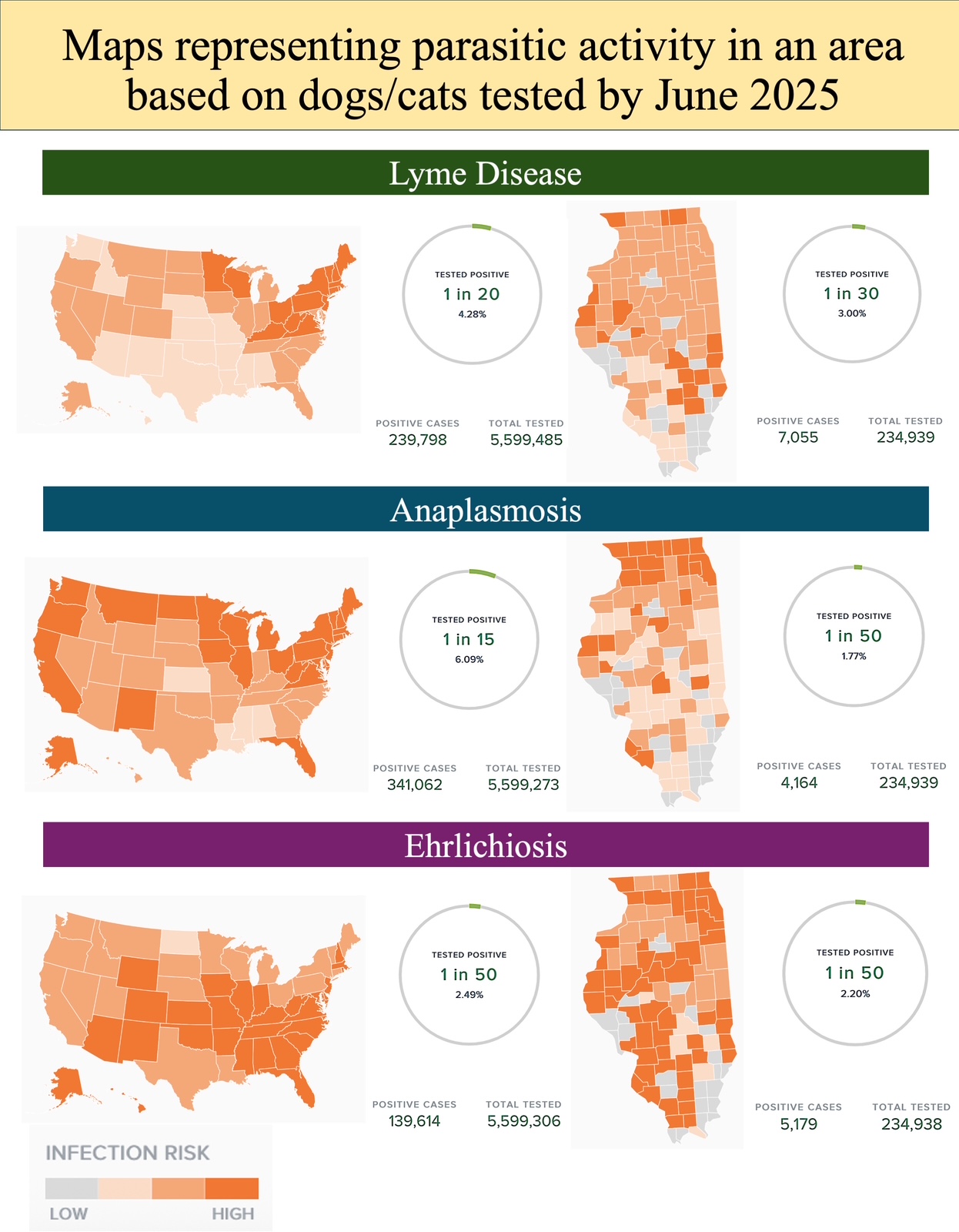

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is the causative agent of human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), and it can infect a wide range of animals, including domestic animals (e.g., horses, cattle, sheep, goats, dogs, and cats) and wildlife (e.g., deer, coyotes, and rodents). In Illinois, human cases of Anaplasmosis and Lyme disease have been reported mainly in the northern part of the state (IDPH). Seroprevalence reports in dogs and cats from Illinois show similar distribution patterns (Figure 3). Because B. burgdorferi and A. phagocytophilum share a tick vector and reservoir host system, the geographic distribution of cases of Anaplasmosis in dogs and cats also parallels that of Lyme borreliosis, and co-infections could be expected as they have been reported in cats2 and dogs4.

Another example is Ehrlichiosis, where the same three Ehrlichia species (E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, and E. muris eauclairensis) cause illness in both humans and dogs. However, E. canis only makes dogs sick, and cases in cats are rare (Morris Animal Foundation). Serologic testing results for Ehrlichiosis in dogs and cats in Illinois during 2025 show a consistent distribution across the state (Figure 3), which corresponds to the distribution of the two vector ticks: the lone star tick, primarily found in southern Illinois, and the blacklegged tick, found in northern Illinois (IDPH).

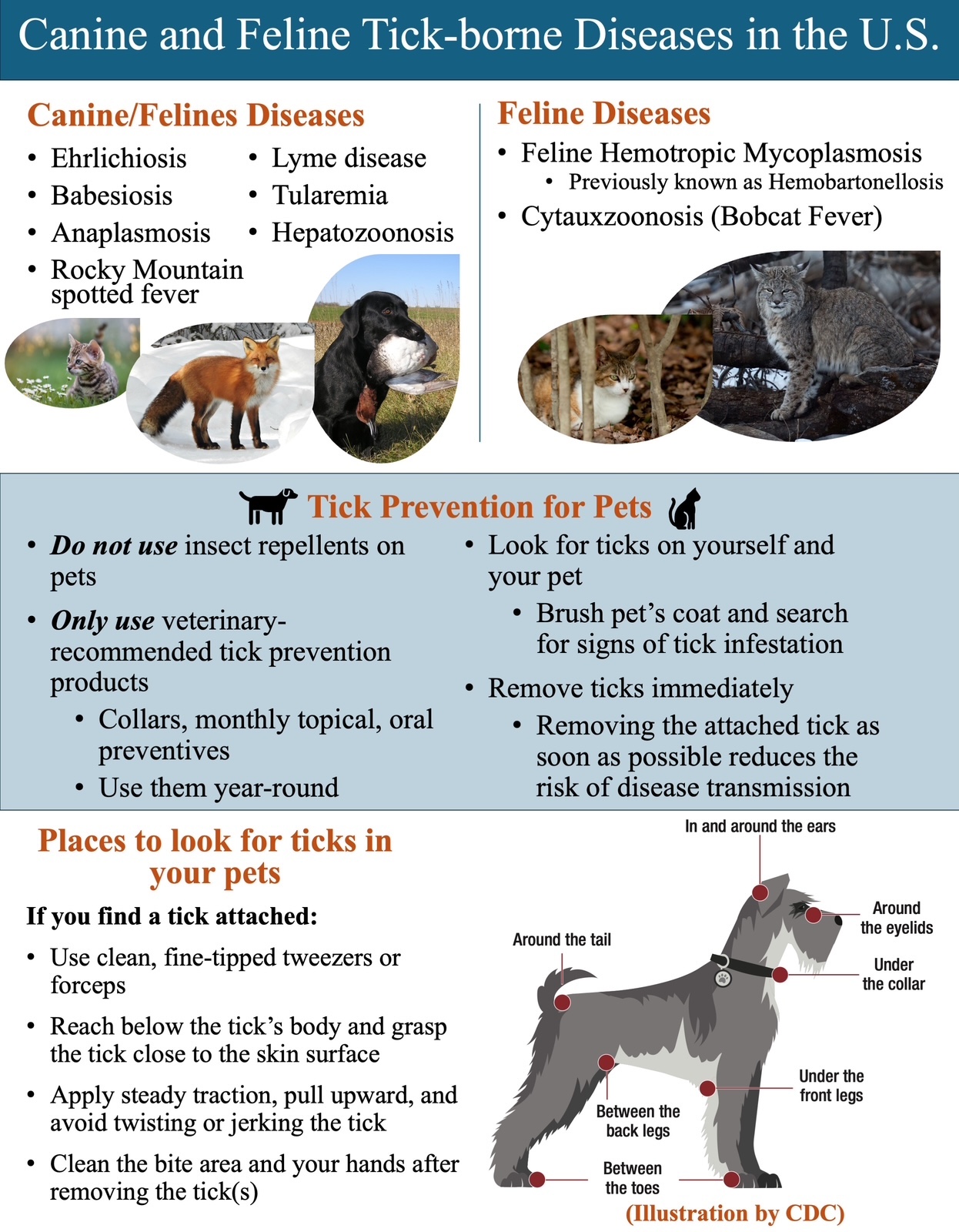

Cytauxzoonosis, on the other hand, is a life-threatening disease of felines (Figure 4), including bobcats. However, it does not affect humans or other animal species. A protozoan parasite, Cytauxzoon felis, causes feline Cytauxzoonosis. Most common clinical signs of Cytauxzoonosis in cats include anorexia, depression and lethargy, which can occur between 5 and 14 days after infection. Dehydration and fever are common findings when cats are examined. Death typically occurs within 2–3 days after the peak in temperature (as high as 106°F (41°C)).5 Because the signs of disease are not specific, it is crucial to take your cat to the veterinarian as soon as you notice changes in behavior, so that a rapid diagnosis, treatment and supportive care can be initiated. Therefore, not all tick-borne diseases affect humans and their companion animals equally, making it important to be aware of the tick-pathogen activity reported in a given area.

Besides infectious diseases, some ticks have been associated with an allergic condition known as Alpha-gal syndrome (AGS). It is caused by the immune system reacting to the sugar molecule alpha-gal, which is transferred into humans through the tick’s saliva as the tick feeds. However, not everyone reacts the same, and the syndrome develops only in some people who have been bitten by a Lone Star tick. The alpha-gal molecule is found in beef, lamb, pork, venison, and meats from other mammals, but not in poultry or fish. This molecule is also found in dairy food products such as milk and gelatin. So, yes, a tick bite can also cause you to become allergic to certain foods that can trigger a severe allergic reaction that can be life-threatening. (CDC; Mayo clinic; Yale Medicine).

Wear tick protection when engaging in outdoor activities (e.g., insect repellent, light-colored clothing, long sleeves and pants tucked into socks).

1) Elias, S. P., Maasch, K. A., Anderson, N. T., Rand, P. W., Lacombe, E. H., Robich, R. M., Lubelczyk, C. B., & Smith, R. P. (2019). Decoupling of Blacklegged Tick Abundance and Lyme Disease Incidence in Southern Maine, USA. Journal of Medical Entomology. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjz218

2) Magnarelli, L.A., Bushmich, S.L., IJdo, J.W. and Fikrig, E., 2005. Seroprevalence of antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in cats. American journal of veterinary research, 66(11), pp.1895-1899.

3) Straubinger et al., 2018. Lyme Disease (Lyme Borreliosis) in Dogs. Merk Veterinary Manual. Available online.

4) Bowman, D., Little, S.E., Lorentzen, L., Shields, J., Sullivan, M.P. and Carlin, E.P., 2009. Prevalence and geographic distribution of Dirofilaria immitis, Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in dogs in the United States: results of a national clinic-based serologic survey. Veterinary parasitology, 160(1-2), pp.138-148.

5) Cytauxzoonosis in Cats. By Alicja E. Tabor, 2022. Merk Veterinary Manual. Available online.

Tick prevention poster

Be tick aware with every step

Defend Against Ticks Year-Round: The Top EPA-Approved Tick Repellents You Need to Know by Jenny Lelwica Buttaccio

Ticks: The unwanted connection between people, pets and wildlife by Elliot Zieman

Dr. Nelda Rivera prowadzi badania nad ekologią i ewolucją nowych oraz ponownie pojawiających się chorób zakaźnych, epidemiologią chorób zakaźnych, nadzorem epidemiologicznym oraz określaniem gatunków rezerwuarowych. Jest członkinią Wildlife Veterinary Epidemiology Laboratory oraz Novakofski & Mateus Chronic Wasting Disease Collaborative Labs. Uzyskała tytuł magistra (M.S.) na University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign oraz tytuł lekarza weterynarii (D.V.M.) na University of Panamá, Republika Panamy.

Dr. Nohra Mateus-Pinilla is a veterinary Epidemiologist working in wildlife diseases, conservation, and zoonoses. She studies Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) transmission and control strategies to protect the free-ranging deer herd’s health. Dr. Mateus works at the Illinois Natural History Survey- University of Illinois. She earned her M.S. and Ph.D. from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Prześlij pytanie do autora