Figure 7: A 1958 aerial view of a borrow pit lake on Cook County Forest Preserve property, now known as Axehead Lake.

Figure 7: A 1958 aerial view of a borrow pit lake on Cook County Forest Preserve property, now known as Axehead Lake.

Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part article of excerpts from a memoir by Bruce Muench, the first technically trained fisheries biologist hired by Illinois in 1950. Photos credited to James Lockart, Head of Wildlife and department photographer.

In the 1960s, interstate highway construction began in earnest in northeastern Illinois. Contingent to the road construction was the excavation of numerous pits along the route to obtain fill for the roadbeds. These borrow pits filled with water, mostly from the ground water table, with little surface runoff, therefore, most of them filled in a short time with fairly deep (15 to 60 feet), clear water. Many of these pit lakes were being developed on public property, much of the land belonging to the Cook County Forest Preserves.

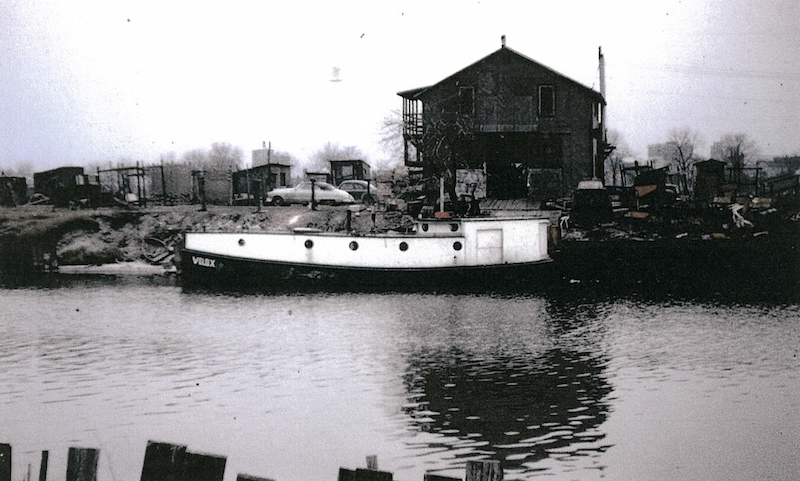

I asked to take photos from the air of some of these sites under construction (Figure 7). Using a state-owned plane from Springfield, I flew along the roadway and photographed part of it in the Cook County area. Many of these lakes developed later into public fishing areas and those on private land eventually became homeowner estate areas. I estimate that at least 100 of these borrow pits, both on private or public property, eventually became useable lakes. I was eventually able to stock many of these lakes with fish, mostly bass and bluegills, and make other management recommendations. Several of the lakes, with oxygenated thermoclines, support trout.

While I was at it with the aerial photography, I also took photos of many of the natural lakes in Lake County (Figure 8). In the 1960s and 1970s Lake County was undergoing rapid growth and development. The landscape was changing from rural to urban and the most rapid change was often around the existing lakes, plus new artificial lake construction was under way as an arm to real estate development.

Two other kinds of lakes began to appear mid-century. One type is the water-cooling lakes built by various electrical power companies to serve as “cooling-down” lakes of their discharge water from their power generators. These lakes are large, varying in size from 100 to several hundred surface acres, and most are also used for recreation, primarily for fishing. Most of these lakes are in the northern half of the state.

The other category of artificial lake was those constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to serve multiple conservation purposes, primarily for flood control and public recreation. All three Corps reservoirs in Illinois exceed 10,000 surface acres and most are in the southern half of the state. These new lakes and reservoirs present new challenges to the state fishery biologists, who were too few and far between to begin with. As late as 1972 there were only 13 of us covering the entire state, including its major river systems and Lake Michigan.

One of our tasks was to perform assessments of pollution-caused fish kills on streams and rivers. This was nearly impossible to do accurately, especially in kills on larger rivers and affecting considerable length of the water body. Major problems include time of notification of the kill, lack of access to all areas of the kill and simply lack of personnel to do the job. Also, we did only fish assessment (as best we could) and we did not assess damage to other aquatic flora and fauna, such as the mussel population.

Common among the causes of fish kills were improper operation of sewage treatment plants, manufacturers discharging heavy metals, agricultural pesticides and discharge of mining wastes. In northern Illinois winterkill of fish under the ice was not unusual, especially in winters of prolonged snow cover of shallow ponds and lakes.

In the mid-1960s, Michigan fishery biologists became interested in introducing salmon into the Great Lakes. Michigan borders hundreds of miles of Great Lakes shoreline. The initial interest was directed at introducing a biological control of an expanding alewife population that had inadvertently been introduced to the Great Lakes via the St. Lawrence Seaway. Michigan also has several freshwater rivers tributary to the Great Lakes that might present suitable spawning areas for salmon. The coho salmon, with a 3-year life cycle, was the initial target for introduction. This proved to be a successful venture, and interest grew with other states bordering the Great Lakes.

While Illinois borders Lake Michigan for about 63 miles it lacks river tributaries of suitable size. Because the salmon introduction had developed an accompanying and eager sport fishery, it looked attractive to us as a possible resource development. In addition, dead alewives were becoming a major nuisance along Illinois’ lakeside swimming beaches during the summer. This latter phenomenon I was able to follow through our test-netting program at Waukegan and Chicago (Figure 9).

For several years the State of Michigan provided Illinois with fingerling coho salmon for Lake Michigan stocking. Later they also provided Chinook salmon. I was able follow these introductions through our test-netting program of the lake, established initially as a lake trout assessment program in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services’ Fishery Program for the Great Lakes. In the early 1970s, I experimented with imprinting Chinook salmon smolts in Diversey Harbor, Chicago (Figure 10) and Great Lakes Naval Station Harbor. It was difficult to establish the extent of the return of adult salmon to these sites, however, the success of the salmon sport fishery in Illinois waters of the lake are well known. I was able to document this to some extent with a special salmon sport fishery investigation, during which I also used an Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ (IDNR) helicopter to observe the extent of the boat sport fishery. Later sport fishing creel censuses were inaugurated by IDNR and Illinois Natural History Survey biologists to quantify the extent of this activity.

In the 1970s and 1980s youth fishing programs were gaining interest, especially in some of the larger urban areas of the country. Much of this was initiated through the Sport Fishing Institute. Partnering with the Chicago Park District, with their many ponds and lagoons, IDNR initiated a youth fishing program (Figure 11). Simple fishing tackle was provided for each participating child and IDNR stocked the water bodies with channel catfish and bullheads. IDNR provided some instructions to the local park district employees chosen to lead the youth. I was the first state biologist to get involved with this new program in Chicago and after overcoming initial hurdles, it turned out to be rewarding. This program continues today, although now with a more structured format and experienced personnel.

As a fledgling biologist in the 1950s, I became interested in the commercial fishery in the Illinois portion of Lake Michigan. In those early years there was an established commercial fishery with vessels out of Waukegan and Chicago (Figure 12). The yellow perch was the principal target species of this fishery, along with the bloater chub, the latter of which was smoked for sale. When I first began working there were perhaps 20 commercial fishermen licensed by the State to fish the Illinois waters of Lake Michigan. I estimate that in the 1950s there were about 12 commercial boats fishing out of Illinois ports. I sometimes visited with the boat owners in the Waukegan Harbor and at times accompanied them out on their fishing trips. Their fishing gear was mainly woven gill nets, and their net drying wheels could readily be observed next to their fishing shacks along the harbor. This acquaintance provided me with valuable experience to be used when I was asked to head up the Illinois Lake Michigan Project and become the Illinois representative to the Lake Michigan Study Committee of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission. By 2019, due to various reasons, no commercial fishing licenses were issued on the lake by the IDNR.

I started conducting a survey of charter fishing boats in response to the sudden increase in salmon and trout fishing in the 1970s. Charter boat captains were provided with information about the fin-clipping we had done in the hope they might look at the fish their clients were taking and report back to me on any clipped fish. The results were disappointing. Although many salmon were being caught off the sites where we had imprinted and released salmon, only a few reports were returned.

Because northern Illinois is about the southern worldwide limit of the natural distribution of northern pike (44 degrees latitude), I became interested in this species and its life history. Northern Illinois river and stream systems also provide some natural habitat for this species. I learned that flooded, marshy areas in the early spring seemed to be essential to pike reproduction.

Considerable numbers of ice fishermen targeted northern pike in the winter, especially in the Fox Chain O’ Lakes. We had a sort of clandestine agreement with Wisconsin biologists to obtain northern pike eggs from the Fox River during their spawning run out of the Illinois Chain O’Lakes and up the Fox River below the dam at Wilmot, WI (Figure 13). Maurice Whitacre, who had taken over the Chain project by this time, was most active in this pursuit. I found a few ponds where northern pike were reproducing, and I conducted some research and egg-taking in one of these ponds (Figure 14).

I doubt if anyone starting a new career knows exactly what is happening or what is likely to happen. With being the newest person assigned to a totally new position with no framework to follow this was especially true for me. I really do look fondly back on those 25 years I worked with the Illinois Department of Conservation. As I write this and search through many of the photographs, those pleasant memories and fellowships flood back.

The author received information from Rudy Stinauer, Al Lopinot and Bill Fritz while compiling this memoir.

Bruce Muench was the first technically trained fisheries biologist hired in 1950 by the Illinois Department of Conservation (now Illinois Department of Natural Resources). He worked for the agency from 1950 to 1970 and again from 1977 to 1981. Between stints with the agency Muench worked with a national environmental consulting firm. After retirement, he established Lake Management Service, retiring in 2015.

Prześlij pytanie do autora