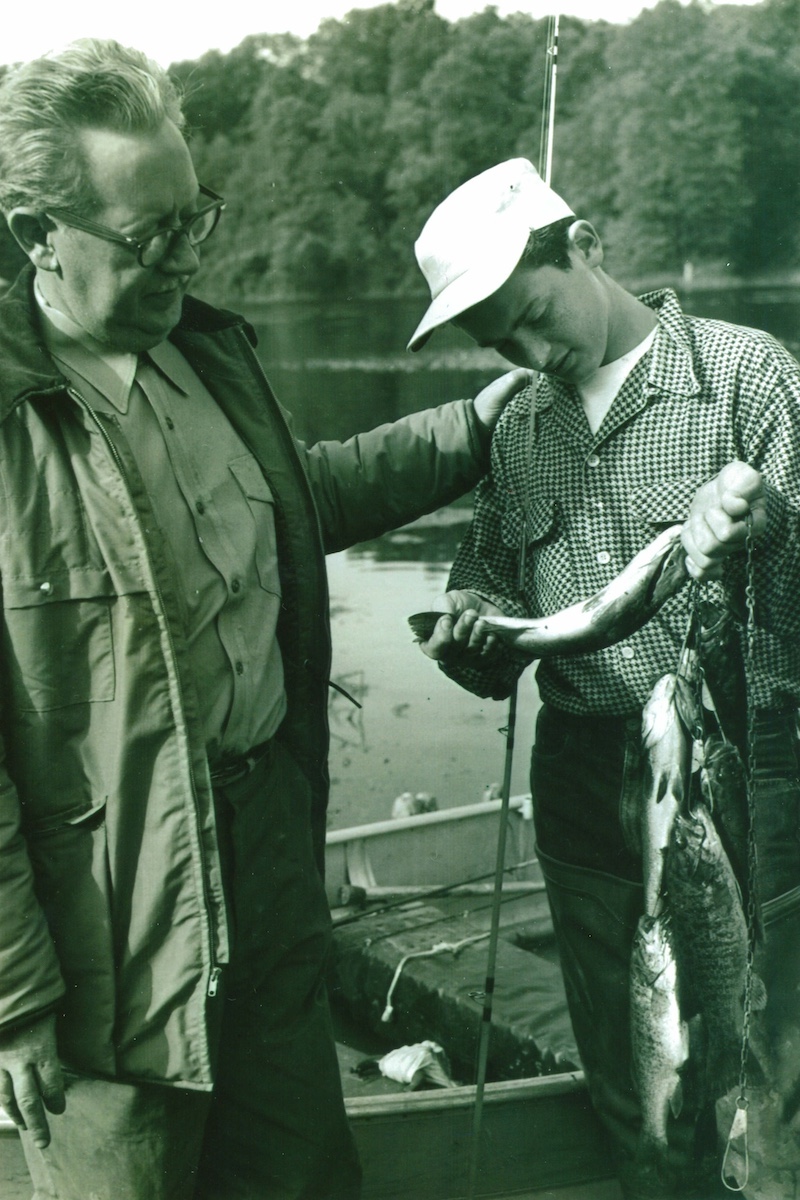

Figure 2: Bill Harth and Bruce Muench in the Illinois Department of Conservation’s Division of Fisheries Office in Springfield in 1950.

Figure 2: Bill Harth and Bruce Muench in the Illinois Department of Conservation’s Division of Fisheries Office in Springfield in 1950.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part article of excerpts from a memoir by Bruce Muench, the first technically trained fisheries biologist hired by Illinois in 1950. Photos credited to James Lockart, Head of Wildlife and department photographer.

Even as a boy, I always was interested in the outdoors, hunting and fishing. When I was in high school in Des Plaines, I used to ride my bicycle up Route 12 to fish in lakes such as Bangs Lake, Lake Zurich and Diamond Lake. I also enjoyed visiting commercial fishermen in their sheds along Lake Michigan, watching as they mended their gill nets and asking them questions. I guess it was natural that I ended up as a fishery biologist.

The following is a personal account of my experience as a biologist with the Illinois Department of Conservation (IDOC) from 1950 into the 1980s. Here is my historical perspective of what it was like to be employed by IDOC as one of the first professionally trained technical personnel.

Essentially, IDOC’s professional staff came on board following World War II with most of the initial biologists and foresters being veterans who had graduated from colleges and universities as beneficiaries of the G.I. Bill. I came out of the Navy in 1946, went to college at Colorado State University and graduated from Michigan State University in 1950.

As a graduate in Zoology/Biology, I wanted to be employed somewhere providing the opportunity to work in an outside environment. I specialized in fisheries so I figured a state with a lot of natural lakes would be appropriate. Because Illinois has relatively few natural lakes, I first sought out opportunities in Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Inquiries in these states got me nowhere. Expanding my field of endeavor was unproductive until I tried my native state of Illinois. In June 1950 I earned an interview with the chief of the Fisheries Division, Sam Parr.

I met Parr (Figure 1) at his home in Decatur as he was bedridden while recovering from a heart attack. He hired me after 20 minutes of conversation, instructing me to contact Bill Harth at the fisheries office in the old Springfield Capitol. The salary would be $2,400 per year, which, based on a 40-hour work week, translated to $1.19 per hour. Chief Parr did not tell me what my duties would be, so I assumed I would get this guidance from Harth (Figure 2), who was the only professional member of the Fish Division, although he was trained as an engineer. I did not know that I was the only fishery biologist that had been hired.

I met Bill Harth in the high-ceilinged office on the first floor of the Old State Capitol. In his early 20s, Harth had been a lieutenant in the army artillery in the Philippines during the war. I was 21 and had been married one year. Parr and Harth were the entire administration of the Fisheries Division, plus one secretary. Some other personnel were scattered through a few fish hatcheries and the Havana Field Station.

I drove home to Des Plaines with more questions than answers and awaited further instructions by mail or phone. I had no uniform, no official identification, no equipment and no transportation other than my own car.

Over the next three years other biologists would be hired, including Merle Price, Al Lopinot, Rudy Stinauer and Bill Fritz, who worked on loan from the Illinois Natural History Survey. Rarely would I be able to meet these other men during my initial three years. After all, Illinois is 385 miles long and at first we had to use our own means of transport. By 1963 there were eight fishery biologists working in the field (Figure 3).

One of the few interdivisional opportunities we were provided was through the Conservation School that the Department operated at Lake Villa on the north end of Fox Lake. There, in a one-week session, classes were held in which people from each Division (Game, Fish, Forestry, Law Enforcement) were able to discuss with each other what they did in their field of operation. The school was operated by Ed Cooney of the Division of Education. I was delegated to give a half-hour presentation, even though I was yet a novice.

Most of my work instructions came via letters from Springfield, but these were few and far between. I took it on myself to drive around to the natural lakes in Lake and McHenry counties and talk to owners of boat liveries and lake-side resorts. I also got acquainted with commercial fishermen on Lake Michigan at Waukegan and Chicago, an acquaintance that was to yield benefits in later years.

After the first five years we biologists met with biologists (Bennett, Hanson, Starrett, Belrose, Larimore, etc.) of the Illinois Natural History Survey (INHS), often in Urbana, but sometimes at the Havana Field Station. INHS staff were professionals, some with professor status at the University of Illinois, who had been conducting research for many years, much of which was focused on the Illinois River.

Among my first pieces of equipment was a boat-mounted electric shocking device that I made by copying equipment (Figure 4) that had been developed by INHS. It was essentially two wooden paddles wrapped with copper wire, powered by a 230-volt A.C. generator. For flotation, in 1953, I was issued an 8-foot Century plywood boat with an 8 h.p. outboard motor. At the same time, I was provided with a Chevrolet coupe. I carried the boat on top of the coupe and put the generator and outboard motor in the trunk. I finally had graduated from using my own car for work and even had an IDOC insignia on the doors of my coupe. We were never issued uniforms but wore our own suntan shirts and pants. We did get shoulder patches for our shirts. I say “we,” because by 1956 there were now nine fishery biologists working in the Department.

I used the electro-shocker to collect fish, first all by myself and later with an assistant, who was sometimes any random citizen I could talk into helping. Later this device was modified several times to improve its efficiency and became available to all the IDOC fish biologists.

By 1956, my wife and I had three children and I thought it was time to try to improve myself professionally, so I chose to go to graduate school and get my master’s degree. IDOC provided me with a working stipend to attend Southern Illinois University Carbondale (SIUC) and conduct a fishery investigation project on Horseshoe Lake, an oxbow lake off the Mississippi River owned by IDOC (Figure 5). I was at SIUC in 1956 and 1957 and during the summer worked on Horseshoe Lake.

Returning home to northern Illinois after graduation I was asked by Bill Harth, the Assistant Chief of the Division of Fisheries, if I would consider working at the administrative level in Springfield. While I appreciated the offer and the confidence that had been placed in me, I was more interested in continuing to work in the field. At that time, I had been stuck at $3,600/year for several years. “Money ain’t everything.”

With the increase in the number of biologists, it was now no longer necessary for me to run all over the state on work assignments. My work as an Area Biologist was confined to 32 counties in the northern third of Illinois, an area where three-quarters of the state’s population lived. Within the area were the two major river systems (Illinois and Mississippi), 34 glacial lakes and the Illinois portion of Lake Michigan.

One of my early chores was the collection of breeder bass and bluegill to supplement those in the rearing ponds of Spring Grove Hatchery in McHenry County. Most of these were collected by electro-shocking in the Fox Chain of Lakes (Figure 6).

The fishing experience for many people living in Chicago and its suburban area during the 1930s and 1940s seemed to center mainly in two areas. One was taking a drive to Fox Chain O’ Lakes and renting a wooden rowboat at one of the many resorts on one of the seven lakes in the Chain. I have fond boyhood memories of coming over the Rand Road hill south of Pistakee Lake and viewing the pastoral scene of many rowboats out of the lake, each bristling with cane poles, bobbers and hooks baited with worms or minnows. The other principal area was fishing for smelt or yellow perch off one of the piers or breakwaters on Lake Michigan.

The author received information from Rudy Stinauer, Al Lopinot and Bill Fritz while compiling this memoir.

Bruce Muench was the first technically trained fisheries biologist hired in 1950 by the Illinois Department of Conservation (now Illinois Department of Natural Resources). He worked for the agency from 1950 to 1970 and again from 1977 to 1981. Between stints with the agency Muench worked with a national environmental consulting firm. After retirement, he established Lake Management Service, retiring in 2015.

Prześlij pytanie do autora