Rebekah Anderson Illinois Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Biologist with a chestnut lamprey on the Mississippi River near Dubuque, IA. Photo courtesy of Cory Anderson.

Rebekah Anderson Illinois Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Biologist with a chestnut lamprey on the Mississippi River near Dubuque, IA. Photo courtesy of Cory Anderson.

A snake-like water dweller with a suction cup mouth full of teeth that attaches to a host and eats its flesh. Sounds like something straight from a science fiction novel. However, these critters are not fictional but exist within our own Illinois waters! Lampreys are from the fish family Petromyzontidae, and not all of them are flesh sucking parasites. In Illinois we have five species of native lamprey, two of which are parasitic and three of which are non-parasitic. We also have one nonnative parasitic species of lamprey, the sea lamprey, which occurs in Lake Michigan and has caused serious harm to the Great Lakes fishery over previous decades.

Lampreys are remnants of a group of jawless fishes that lived 350 million years ago, making them one of the oldest living vertebrates. They have skeletons made of cartilage and long, tube-shaped bodies. They lack pectoral and pelvic fins and have no scales on their bodies. They have seven pore-like gill openings along each side of their head, with a single nostril in the middle of their head. You are not likely to encounter this ancient critter on your treks to our Illinois streams and rivers, but it’s important to know that lampreys are part of Illinois’ natural heritage and they do contribute to biodiversity in our aquatic ecosystems.

The sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) is an invasive parasitic lamprey species native to the Atlantic Ocean that was first observed in Lake Michigan in 1936. They were introduced to Lake Michigan when the Welland Canal was constructed between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario in 1829. The canal circumvented the largest natural barrier to fish migration to the Great Lakes, Niagara Falls. Adults range in size from 14 to 19 inches. Adults are larger in size because they are adapted to preying on large ocean fish. Because of their size and the vulnerability of our smaller freshwater fishes, sea lamprey severely decimated the populations of lake trout and whitefish in Lake Michigan in the 1940s and 1950s. In the 1960s a pesticide selective to lampreys was developed and used to kill the larval forms in streams, bringing the population under control. Sea lamprey are only found in Lake Michigan and its tributaries, whereas native lamprey species are found in water bodies throughout Illinois.

The lamprey life cycle occurs in two distinct stages, larval and adult. A larval lamprey is called an ammocoete. Ammocoetes look like adults but lack eyes and their mouths are horseshoe shaped hoods rather than circular sucking discs. Ammocoetes burrow into the soft sediment of small streams where they feed on microscopic organisms and organic particles. This stage lasts three to six years before they transform into adults. Transformation lasts several months, occurring in late summer and fall. During this transformation, larvae develop better eyesight, a suction-disc mouth and reproductive parts. During this process ammocoetes do not feed and become rather small in size as a result.

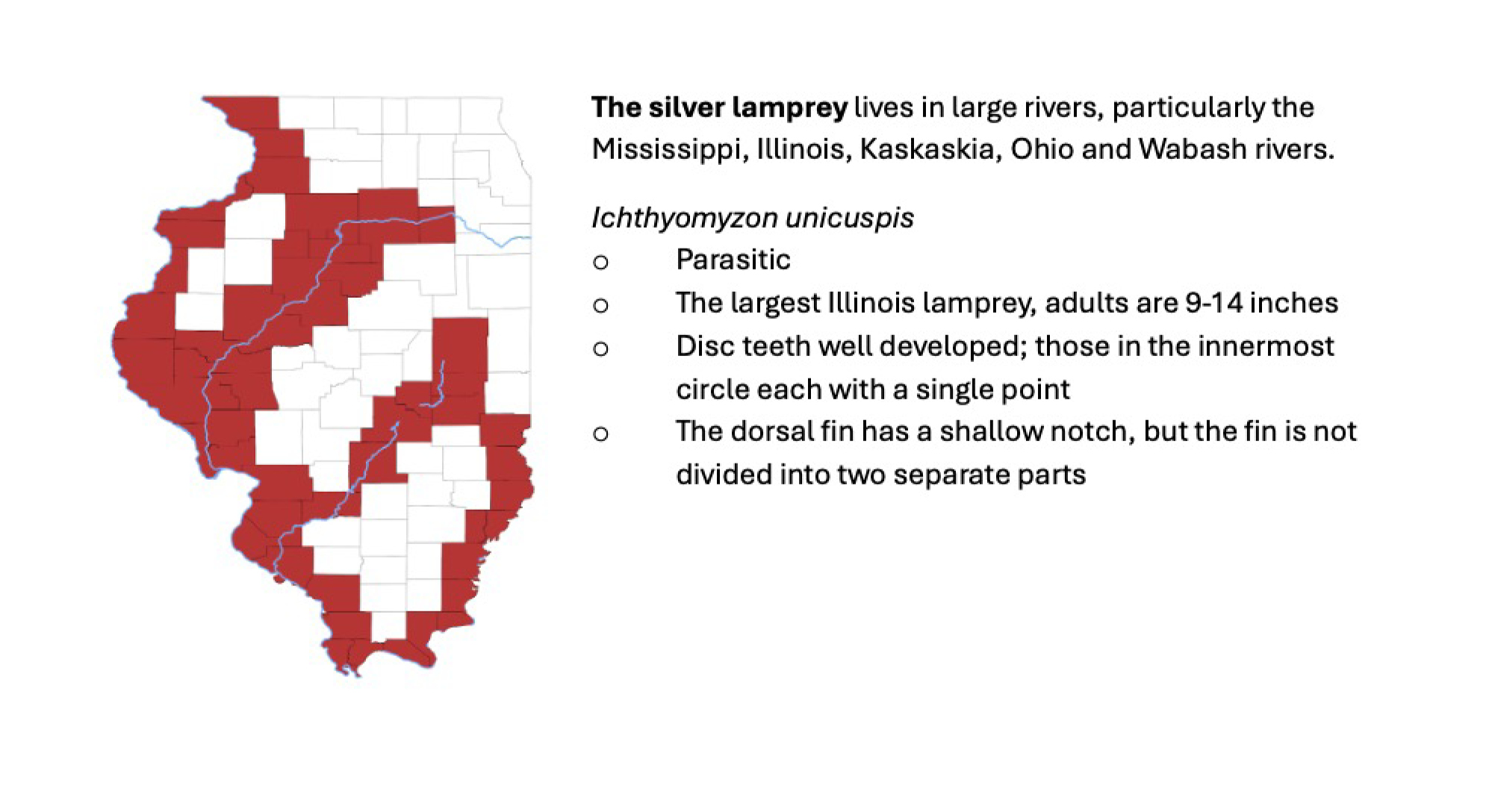

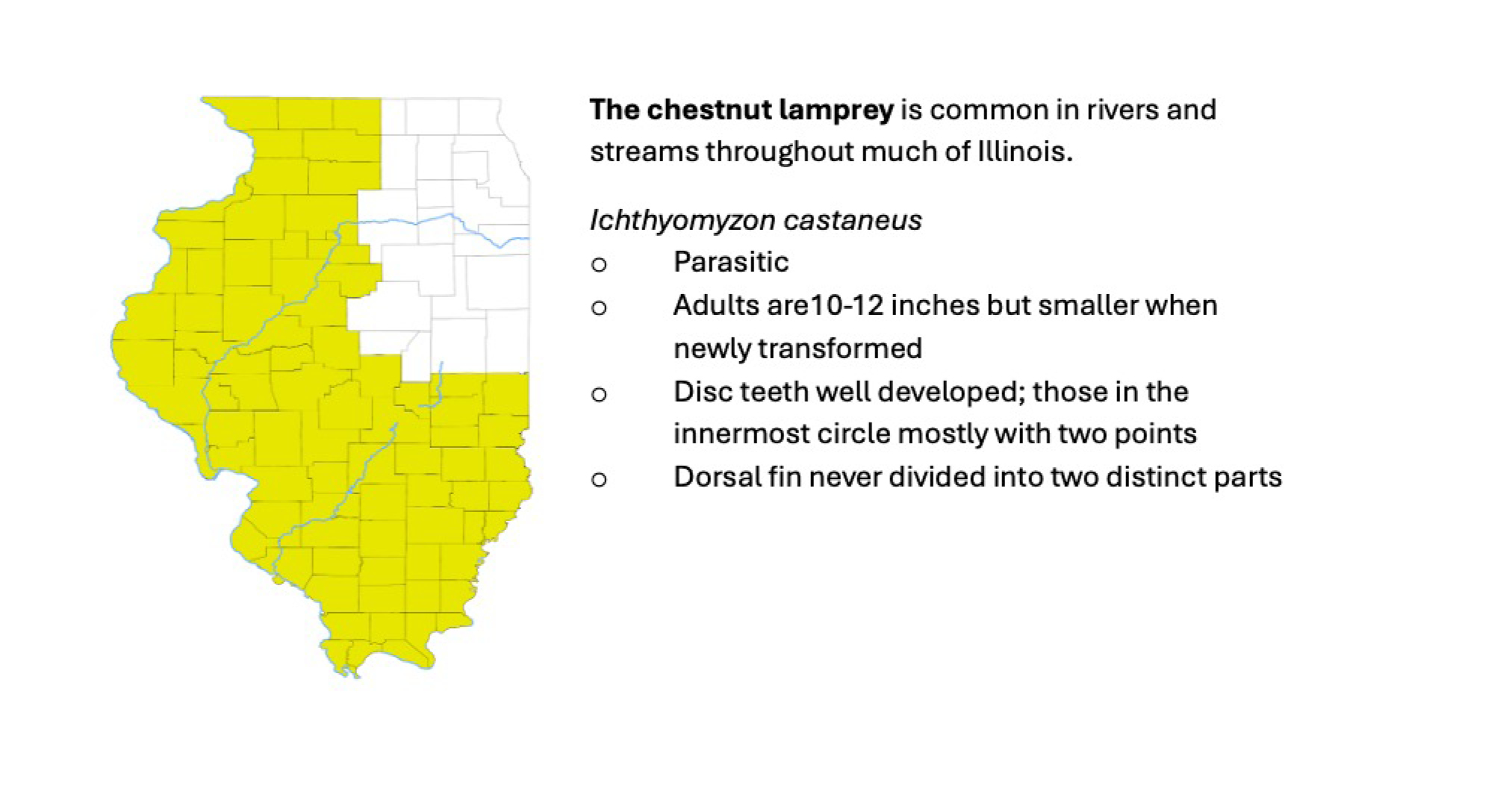

After transformation, a lamprey follows one of two courses depending on if its parasitic or non-parasitic in nature. Parasitic lampreys, such as the silver and chestnut lampreys, migrate to large rivers after reaching adulthood and then attach themselves to other fishes, sucking blood through a hole rasped in their host by a hard tongue-like structure in the middle of their mouth disc. It takes a lamprey several days to finish its blood meal, after which it drops off. The host fish usually does not die as a direct result of the attack but may die of secondary infections that develop from the wound left where the lamprey was attached. Native parasitic lampreys are not extensive enough in number to cause detriment to our native fish populations. The parasitic stage lasts one to two years, after which the adults return to smaller streams to spawn.

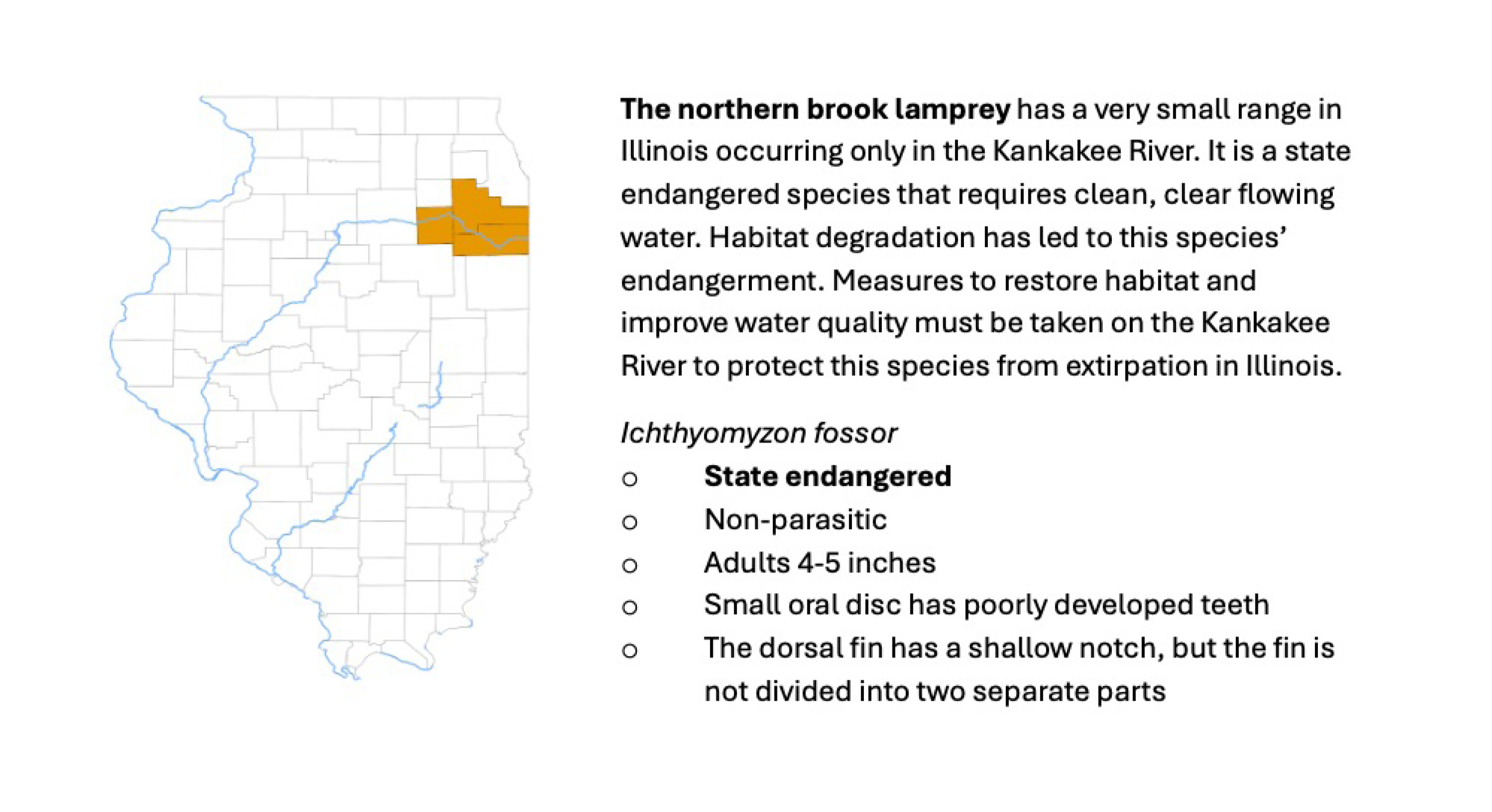

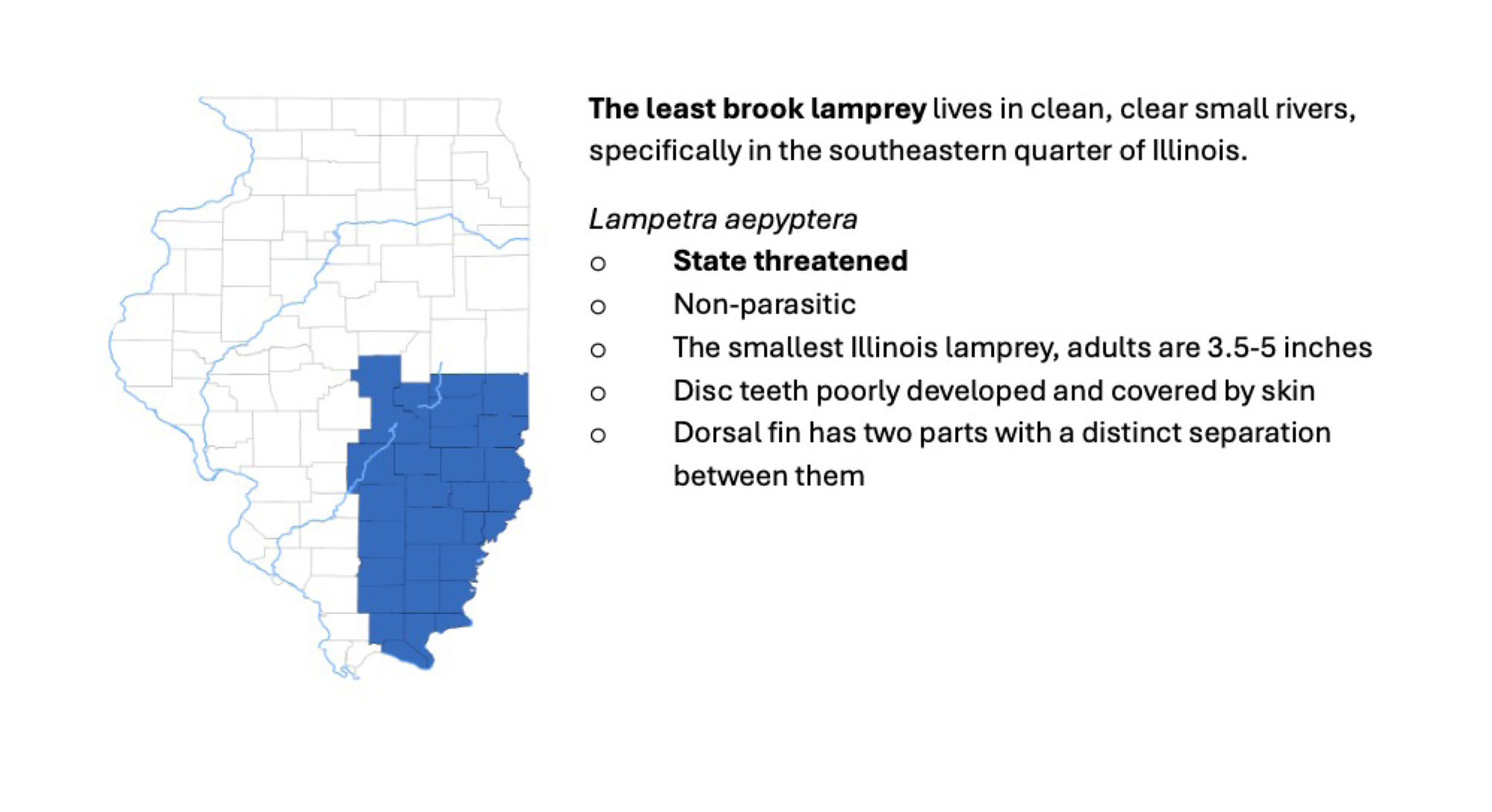

Non-parasitic lampreys, such as the northern brook, least brook and American brook lampreys remain in smaller streams after transforming to adulthood and do not feed at all because their intestines are non-functioning. As a result, these lamprey are much smaller in size than the parasitic lampreys. As adults non-parasitic lampreys are merely in the reproductive phase of life. The spring following their transformation they spawn and die

Spawning occurs upstream gravel riffles or beneath rocks and other objects in deeper, swifter sections of streams. Lampreys build nests by removing stones using their suction-disc mouths and fanning fine material away with violent body vibrations. Sometimes nests are occupied by a single male and female pair or communally with 20 or more lampreys in a single nest. Adults do not feed once spawning begins. When spawning is finished they die. Non-parasitic female lampreys can deposit more than 1,000 eggs during a spawn while parasitic female lampreys can deposit at least 10,000 eggs during a spawn. Eggs are fertilized and hatch into ammocoetes after 10 to 12 days, although most will not survive into adulthood.

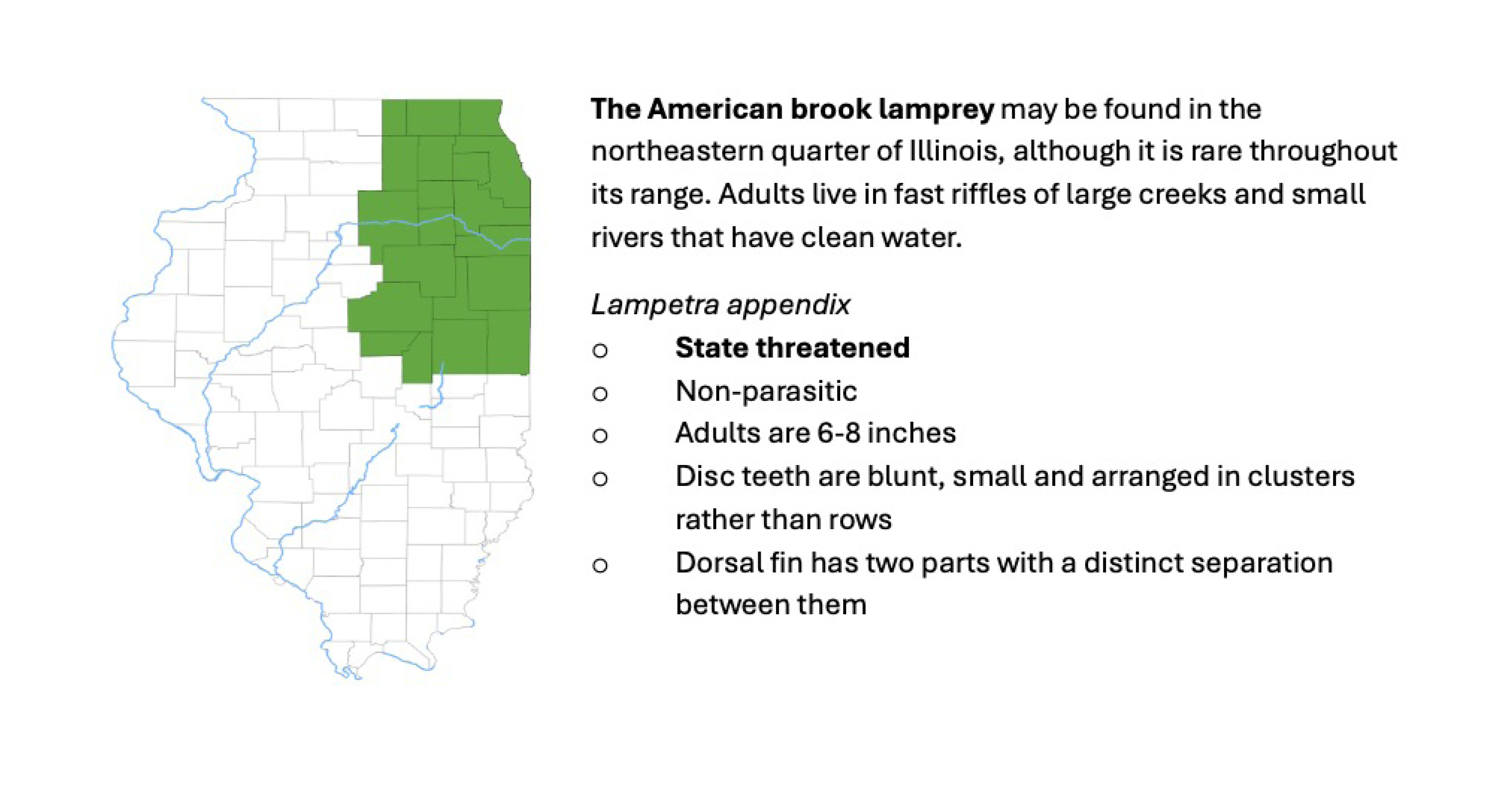

Lampreys are indicator species, meaning their presence reflects the health of an aquatic ecosystem. The least brook, American brook and northern brook lampreys are sensitive to pollution and habitat degradation. They prefer clean, clear water with quality riffle habitat for spawning. Unfortunately, all three of these lamprey are either state listed threatened or endangered because these conditions are scarce in many of our aquatic systems. Conservation efforts to improve water quality and restore habitat are essential to protect Illinois’ native lamprey from extirpation. Prioritizing these conservation efforts will not only benefit lamprey, but also many other fish species that have commercial and recreational value.

Rebekah Anderson is an Upper Mississippi River Biologist with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Fisheries. Her jurisdiction covers the Mississippi River where it enters Illinois at the Wisconsin border, down to the Quad Cities area. She enjoys finding unique and somewhat rare fishes such as lampreys, in her sampling ventures.

Prześlij pytanie do autora